Reflections for a Sunday: The Lionesses of Egypt

"If the traditions and culture of the East are blindly compelled to hurt a woman’s dignity, insult and degrade her in the name of cultural unity, then I am ready to burn myself." ~ Huda Sharawi

You can listen to me read this essay here:

One-time or recurring donations can also be made at Ko-Fi.

“So, if the traditions and culture of the Eastern community are blindly compelled to hurt a woman’s dignity, insult and degrade her in the name of cultural unity, then I am ready to burn myself. If it means facing prosecution and rejection to highlight these difficult truths, I intend to vocalize my pain and start a revolution for the silent women who faced centuries of oppression.” ~ Women between Submission & Freedom, Huda Sharawi, 1879-1947

I didn't know the extent women suffered under Islam until I lived in Egypt. It was there that I discovered brave women writers, and I began to read their words.

One hundred years ago Huda Sharawi stood up for the rights of women. What would she say if she saw how that oppression hasn't ended but is spreading farther, even across the Western world?

Huda Sharawi grew up in the harem system, where women were confined to their homes, could not be in the presence of men except from their own families, and wore face veils when going outside. She was married at age 13 to her older cousin, Ali Sharawi, who was already in his late 40s.

Huda was fortunate in that she was from a prosperous family, and she received an elite education. She used her education and her position to fight for women's rights. After returning from a conference in Europe, she removed her veil on a train in Cairo, causing a sensation. It is thanks to her and others like her that life improved for women in Egypt. But that freedom didn't last.

One sad thing I discovered is that there are no women, at least that I know of, outside the upper class, who have had a chance to attain a voice. So, we never hear what these silent women from 90% of society have to say. I despair that the day will ever come when we hear their voices. Imagine if they could speak, how powerful their words would be.

I did meet one woman from the villages of Luxor, who refused to live under these restraints. Her name is Marwa.

I first learned about Marwa at El Bairat Hotel, where I would sit in the evenings beneath a giant mango tree to watch the sunset across the Nile. The moon rises right above Luxor Temple and it’s a sight to behold.

Everyone was talking about Marwa that night. She was in Cairo, having a conversation on television with none other than Egyptian President, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. He had heard about her through a local news station, how she worked like a man to support her family.

Marwa had no brothers, just sisters, and she had taken on the responsibility of breadwinner. She was known for wearing a man’s jellabiya and doing a man’s job, working in construction, in the fields, lifting heavy objects, doing what she could to earn money for her family. In a place where I never saw a local woman driving, she had bought her own truck and used it for her work.

When all of this was described to me, I realized who she was. I had seen her on occasion, driving around in her truck. On the West Bank, everyone knows everyone else’s business.

Such actions weren’t usually acceptable for women yet somehow, Marwa got away with it, even becoming a local celebrity.

As I listened along to her interview with Sissi, I asked for it to be translated. The part that stood out to me was when Sissi asked Marwa why she wasn’t married. Being the blunt person she was, she said she wasn’t interested, she was too busy for a man, and she liked her freedom. Sissi then said he’d make a deal with her. If she’d get married, he’d buy her a house. Marwa laughed. Everyone listening to the interview laughed along. But Marwa refused to agree to the deal.

What would you like, then? he asked.

Marwa said she’d like a bridge to be built from the villages of El Baeirat on the West Bank to the main city on the East Bank. She explained how difficult it was for the poorer people who lived on the West Bank to get across the Nile to work or to shop. As it was, they had to either take the ferry and then walk great distances, or they had to take a bus across a bridge much further down the river, which took hours and was way too expensive.

I’m sure this was the last thing Sissi expected Marwa to say. He probably thought she would ask for something else for herself—something that didn’t include a husband in the deal. But what could Sissi do except promise he’d “look into it “.

As far as I know that bridge still hasn’t been built.

Of course, Marwa became somewhat of a living legend upon her return to the West Bank.

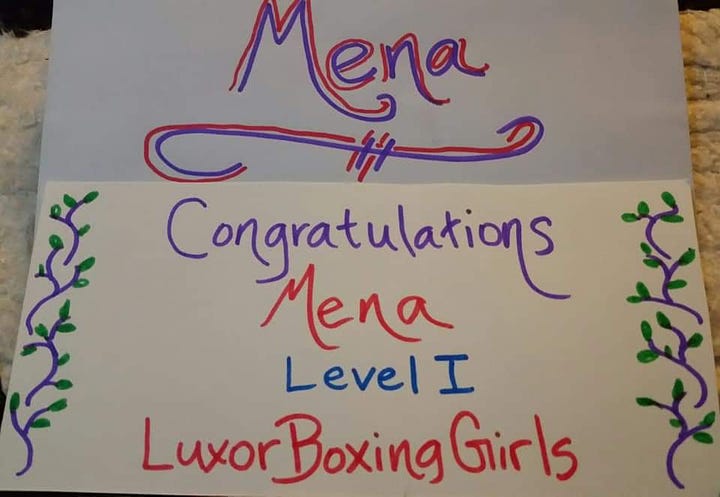

I got to know Marwa when I started Luxor Boxing Girls. I didn’t move to Luxor with the intent to start such a club. The idea grew organically over time. No one would have ever accepted it otherwise. The first thing I did when I moved into my villa with its lovely garden (rent $350 a month) was to put up a boxing bag on my terrace.

As I said, nothing remains a secret in Luxor, and before long, word spread that there was this American woman, boxing on her terrace. Soon curious children started showing up, begging to try on the gloves and hit the bag. In the beginning, it was all boys. But after a while, girls came, too. Sometimes, I’d come home to find ten to twenty eager kids, yelling “Box, box!” outside my gate.

I couldn’t teach all of them, so I came up with the crazy plan to teach a group of girls, not knowing how it would even be possible. By this point, I had lived in Luxor for over a year and people knew me. I realized it wouldn’t be easy. How to find the girls?

In order to teach girls, I had to obtain the approval of their fathers. I could not do this myself, so, Mahmoud, the young man who was the caretaker of the villa, said he would go into the villages and find a group of girls and negotiate with their fathers for them to take boxing classes.

Now, this is the part of the story that is really sad. The only way the fathers would allow their daughters to box was if I paid the fathers money. Ordinarily, it’s the parents who pay for their children to take sports classes, right? It’s the parents who see the value for their children. I would never have even considered charging the parents to teach their daughters, but I was a bit shocked that they expected me to pay them. I should have known better. Everything in Luxor is about money. That is the only way to determine value. Still, I hadn’t expected fathers to sell their daughters like that.

I was by no means well off, but it was the only way they would agree to the classes, so Mahmoud negotiated for me, and we reached an agreement. I would pay the fathers the money once the girls had completed a course of a certain number of lessons, not before.

But how would the girls get from the villages to my villa. That’s how I met Marwa. Mahmoud was friends with Marwa and talked to her about it. She agreed to transport the girls.

The first day, Marwa brought the girls in her brand new, bright red van. The girls climbed out, looking shy and nervous. I couldn’t blame them. They had no way of knowing what their parents had gotten them into. I was nervous, too. Afraid maybe they wouldn’t like it. But it only took a couple of classes before they were having fun, yelling, laughing. To punch and kick, this is something they had ever experienced before. Oh, of course they got into scuffles growing up. I’d lived in a Swiss village as a child, and in a village in communist Yugoslavia when I was married, so I knew that girls had to be tough like boys.

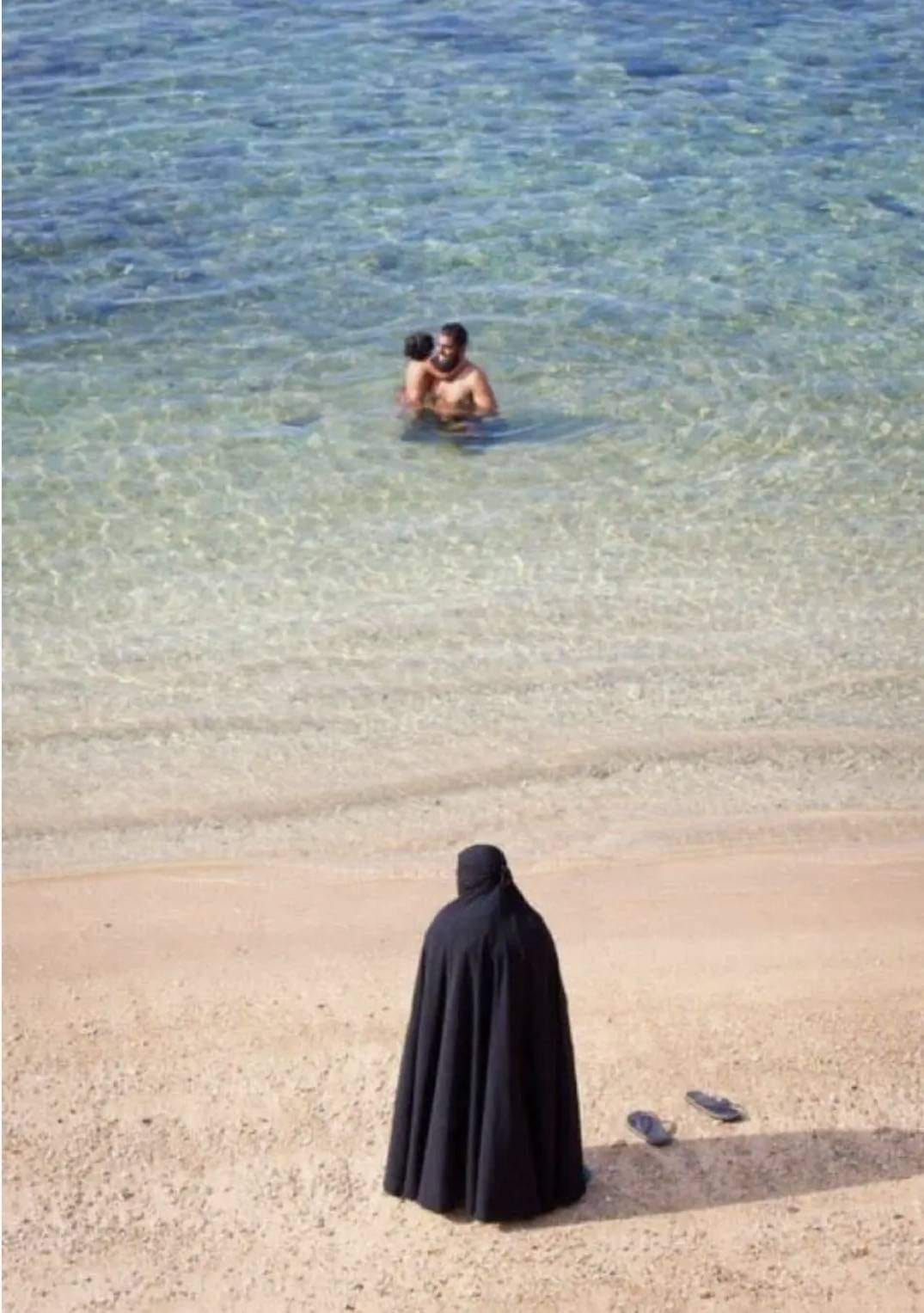

But that freedom only lasted up until puberty for girls in Egypt. Then, they were separated from boys, they were cut (female genital mutilation), and protecting their virginity became all that mattered.

This type of training, disciplined and focused, learning how to be physically powerful was not something girls learned in Muslim countries. It’s not something most girls learn anywhere.

I was amazed and gratified to see how strong and determined they were. All that untapped self-confidence hidden inside came out and blossomed. When we had competitions to see who could hold a squat the longest, no one wanted to be the first to give up. When they had to do sit ups, no one stopped until the very last count, no matter how hard it was. Their determination knew no bounds.

Part of the deal was for me to teach them some English. It naturally followed that they taught me some Arabic. They learned to count in English, loud and with confidence. I learned to count in Arabic. I taught them how to use their energy, expelling it at the moment of impact with the punch or the kick. They learned combinations and did a bit of light sparring. Marwa helped me with demonstrations which they thought was hilarious.

All of this was especially meaningful since I had dreamed of learning martial arts as a child. I had grown up in a conservative Christian household and my parents believed karate—anything from the East—was of the Devil. I didn’t think that, but it didn’t much matter what I thought. This was back in the 1970s. While most girls were dreaming of going to dances, wearing make-up, and, I don’t know, maybe wanting to be movie stars, I wanted to be a Ninja warrior, a female Bruce Lee. So, here I was teaching girls in a Muslim country how to fight when I had been denied that training back home by my Christian parents. Life had some strange twists and turns.

I have sometimes wondered how different life might have been if I’d been able to start my martial arts training as a teenager. I doubt I would have put up with my physically abusive husband. On the other hand, my experiences as a grown woman, the powerlessness I felt, was a driving force in my own dedication to train. Once I became proficient, I wanted to share my knowledge with other women and girls, so they would never face what I had faced.

Of course, Marwa and Mahmoud expected to be paid. That, I didn’t mind at all. They became assistant coaches. Mahmoud had the t-shirts made with our names on the back and Luxor Boxing Girls on the front. I was known in Luxor as Sama, which means sky, so that was my name on the back of my shirt. I cannot tell you how excited and proud the girls were to get those shirts, each one with their name on the back.

When they put their shirts on for the first time, it was as if they each grew five inches.

A few times, I gathered with the girls at Mahmoud’s family home in his village for dinner. When the boxing course was completed, we had a ceremony at his home. I handed out the certificates, with the money for their fathers inside. Not a single mother or father showed up. But you can be sure, when the girls came home with the money, they took it.

After that, I started having problems with Mahmoud. It was always the same in Luxor, the men always wanted more. Sometimes we would drink tea together on my terrace in the evenings and he would tell me he was looking for a wife in his village.

“What kind of woman should she be?” I asked.

“She must be modest. Not look up on the street. Obey me. Be nice to look at. Be a good wife,” he said.

I asked about love. But he didn’t seem to understand that concept. She just had to be a good wife. Chosen by his family. Even as he spoke like this, he tried to convince me that I should marry him. It became a problem. One evening, he tried to kiss me, and I had to push him away and throw him out of my garden. The next morning, he showed up with fresh bread baked by his mother and apologized.

The lies in Luxor are never-ending. Mahmoud still didn’t give up trying to get me to marry him, although he never tried to touch me again. He assured me he hadn’t found a wife in the village, he never would, he just wanted me, blah blah. No woman could compare to you, he said. I wasn’t impressed. Nor was I surprised to find out he was engaged all this time to a village girl and the wedding planned.

It took me a long time to understand how these men could be so blatant in their lies. They had no shame, even when they were found out, they expected things to just go on as normal. There was no sense of consequences for betrayal. The reason, of course, was because all foreign women were infidels, and no matter how much they smiled and lied to your face, they really thought of you as prostitutes to be used for sex and money—money being the most important.

How could that perception ever change? It wouldn’t when these men didn’t even respect their own wives. I wondered what would happen if someone like Marwa was given a bigger platform. But she wasn’t educated, she was a rough village woman who didn’t write poetry or books like the educated women of Cairo and Alexandria. She had no time to participate in protests and I doubt she would have understood the value of such a thing. Even though she made it to Cairo, interviewed by the president, she was still confined to her small world and the expectations that world had for her. Her freedom was important to her, but it was a personal freedom, not something universal for all women. I don’t think she ever considered that women in Egypt should actually be “free”.

I wasn’t able to continue the boxing classes. Covid came along and the entire world changed. But I was already feeling fed up, thinking that once I got out of Egypt, I would never return. By the time I started the boxing classes, I’d caused a bit of a ruckus in Luxor. A group of men had tried to scam me the same way they did all the foreign women in Luxor, by convincing me to buy a property that I would think I owned, but I never actually would. As a result of exposing their scam, I’d made some serious enemies.

If you want to live in Luxor, or in a Middle Eastern Muslim country, there’s a certain point when you have to decide if you are going to accept the horrors that go on in the shadows—in which case you stay—or you are not going to accept them—in which case you have to leave. I realized I had to leave. If I had stayed in Luxor, I would have ended up in jail or dead, because unlike the other women living there, once I knew the truth, I could never quietly go along with the lies.

The last time I saw Marwa, it was not long before Gitte and I were able to get on a plane and escape Luxor at last. It was the night before Gitte’s villa got attacked, which I wrote about in Tales of Eclipse: The Lost (Foreign) Women of Luxor and both of us were feeling increasingly unsafe. I’d gone to stay for the night at Djorff Palace, invited by the owner. Just one night of peace before all hell broke loose.

As so often happened in Luxor, the owner had married a much younger local man and had built this incredible hotel bit by bit over time. I really liked this woman. She was a character, extremely smart. As I sat with her in the evening, listening to her fascinating life stories, her husband came to visit. As always, I wondered how she and all the other foreign women convinced themselves that their husbands loved them.

But then, what was the alternative? This woman was no fool. She had built a fairytale palace on the Nile, like something out of the Arabian Nights, and it was her little kingdom. Was it any better to live, say, in Los Angeles, battling traffic on the freeway to and from a job that you hate, married to a boring old man who sits in front of the TV watching football?

So, we all make our compromises, according to what we want out of life. For me, I just can’t live with lies—although I'd be a liar if I said I’d never been taken in by a lie or had never told a few myself.

The next morning as I left my room to return to Gitte’s villa, there was Marwa, cleaning that vast realm. We smiled at one another. Again, I imagined her on a platform somewhere in the United States, speaking up for the voiceless women of those villages, holding in her hand a microphone instead of a mop. But there she was, cleaning this foreign woman’s paradise, an integral part of the scams that made up life in Luxor.

What woman could ever break free of the confines of that world? What woman could ever even imagine it was possible. I know things are better than they once were. The older sister of Aya, one of my boxing students, was attending a nearby college. I often visited Aya’s home and had tea with her family. Her sister wanted to box, too, but she was beyond the age that her father would allow it. I asked her what she would do with her education. She said there was only one thing to do, go into the tourist business, working perhaps in a hotel, get married and stay in the same village.

There were many young women in Luxor, working in the shops. Still, they lived under strict rules. They did not leave their families. They did not venture across the sea. Maybe at some point one of those girls I’d trained would find a way out, she would remember what it was like to punch and kick and she would punch and kick her way into a university and get an education beyond what was expected of her. Maybe she would become a writer and tell the stories that no one had ever told.

If Marwa and all the other girls in Luxor were taught the writing of the lionesses of Egypt, their own women Egyptian authors and activists, how different their lives would be. How wide open their worlds would become. But it’s doubtful such writing would ever be a part of their curriculum.

I think of Doria Shafik who wrote Harem Years, 1879-1924. Shafik was full of fire. She stormed the parliament, went on a hunger strike, took a trip around the world to speak on Egyptian women’s conditions, got women the right to vote in 1956, and published works like her novel The Slave Sultane, as well as her memoirs, and poetry.

For the crime of being such a rebellious woman, Shafik was put under house arrest by Nassar for twenty years. Tragically, unable to bear her prison any longer, she took her own life in 1975.

I think of these incredible women and how brave they were and how they fought to be free. If I could, I would find a way to get their writing into the schools. But it is already too dangerous for me to return to Luxor.

How it happened that those men tried to scam me and how I got the better of them is for my next chapter.

Hry

Hey

And what gets me about this? Women in the west moan about being oppressed, being repressed. And while I know there are women in America who do suffer-I grew up and live now in the poor Appalachian region-it is not anywhere close to being the mass wide systemic oppression that feminists claim. Women in the west have rights they easily take for granted that many women in Muslim countries who truly live under terror and real oppression scarcely let themselves dream of.

I am in awe that you did something so positive for girls in Luxor (and surprised you got as far as you did!) Your insight is spot on and expressed so well. I have been there and it’s hard to understand that even the few educated women we met and spoke with seemed to embrace their shackles. It also took a while for it to sink in that women were truly regarded as below men, such was my naivety and own belief that all people are equal. It is shocking. Seems like a lifetime ago.

I hope your lessons helped your young boxing students