Reflections for a Sunday: The Gates of Heaven & Hell

As a child, I walked through Dachau. I met survivors and listened to their stories. That’s why it's so important for me to share what I remember so the lies spread today don't overcome the truth.

One-time or recurring donations can be made at Ko-Fi.

You can listen to me read this essay here:

Yesterday I learned about the Last Eyewitness Project: Telling the Stories and Preserving the Dignity of Aging Holocaust Survivors.

Please watch the very poignant short video below, about 3 Jewish men who arrived at Auschwitz on the same day and were tattooed 10 numbers apart. 73 years later, thanks to the Last Eyewitness Project, they met for the first time and shared their stories.

When the interviewer asks how it worked when they were tattooed the one man says, “You stood in line, you were naked, with a rusty razorblade somebody cut your genital hairs, somebody cut your hair (on your head), somebody gripped your arm and there was a guy sitting there with a little cardboard and he wrote down your name and he picked up your arm—and we were lucky, these numbers were decent because the guy who tattooed me knew already (how to do it) but there were some people who had numbers from here to here (meaning all the way up their arms).”

The other elderly man recounts how in September 1944 he came to Birkenau with his family in a cattle car. Even all these years later, it is traumatic for him to tell what happened next, but he does, with great courage. It has always amazed me how survivors are able to carry on, laugh, tell jokes, raise families, live full lives. The resilience of the human spirit is inspiring.

At the same time, it’s horrifying to see antisemitism increasing around the world. Or, perhaps, it’s just that people now feel emboldened to let out what they have always felt inside. On social media, especially on Elon Musk’s X, Holocaust deniers spew their hatred unchecked.

Huge accounts such as Jake Shields @jakeshieldsajj make it their mission to feed the flame of Jew Hate, by posting things like this:

They will take a fact, such as that Jews were killed in gas chambers, and try to prove it was a hoax, thereby disproving everything else about the Holocaust.

Isn’t it strange how no one tries to deny Stalin starved millions or that 18,000,000 passed through his gulags—surely, it’s got to be an exaggeration. But when it comes to the planned extermination of the Jews by Hitler, this small population of people who God has miraculously protected for so many centuries—it is all a fabrication of Jews who “control the world”.

There is ample evidence of gas chambers being used to kill Jews and others, which you can read about in Traces of War and many other places. But for those who want to deny the Holocaust, such facts will not matter.

They will not listen to actual Holocaust survivors like these 3 Jewish men:

They will listen to someone like MMA fighter Jake Shields and become one of his 663,900 followers. He’s so cool, right? I mean, look at his tattoos compared to those old Jews. What do they know compared to an MMA fighter?

Within Jake Shields virtual world, his followers can live out their delusions with others who are equally deluded, feeding each other’s hatred, until there is no doubt in their minds that they are right, and actual eyewitnesses are wrong; like these men who suffered beyond comprehension and saw their family members killed and have had to live with the memories all these years. And then, when they tell their stories, they are just liars, part of some Jewish plot.

Soon all these eyewitnesses will be gone. Who will carry on their stories? Who will remind us of the truth when so many have covered it with lies?

As a child, I walked through Dachau. I listened to stories of witnesses. That’s why it is more horrific for me than perhaps many others to hear the lies now, seeking to drown out the truth. That is why I share my stories, so they will not be lost in time. As a child of ten within a short space of time, I experienced in Germany the hell of Dachau and the heaven of a sanctuary called the Sisterhood of Mary. I saw the good and the evil in clear contrast, so that there was no doubt which was which. It gave me hope because I saw how much more powerful good was than evil. Not in the way of the MMA fighter, not in the way we like to think of power. In a spiritual way. In the way of TRUTH. Truth will always overcome lies.

Here is my eyewitness account, which I call THE GATES OF HEAVEN AND HELL Germany, April 1966

As I looked out of the VW van window that day at the entrance to Dachau, I didn’t know what awaited me. I don’t even think my parents were prepared for what awaited us. How could anyone adequately prepare for hell? As far as I was concerned, this was just another stop on an interminable journey, a museum of sorts, or so I understood, and I wasn’t thrilled to be visiting yet another museum.

The front of the building looked unassuming, boring, a place I wasn’t interested in going. But there was no staying in the van. The sliding door opened, and I got out with the rest of my family.

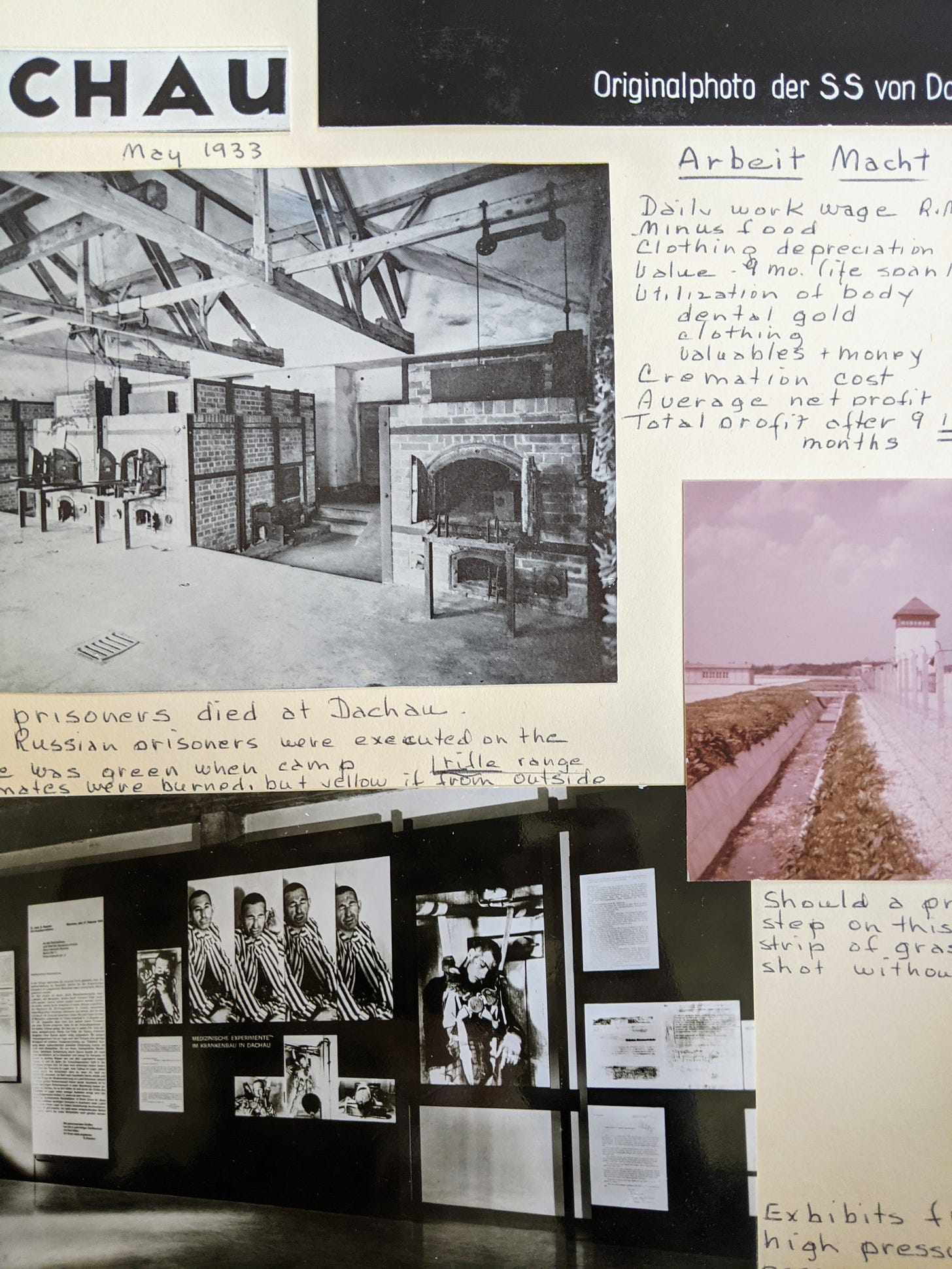

I walked up to the iron entrance gates and stood beneath the words welded into the arch, “Arbeit Macht Frei” or “work makes one free.”

Mom, who loved history, gathered us around her and said, “Imagine it’s the end of the 1930’s and you are children torn from your parents, lost, confused, scared, not understanding why you are here or what is happening, and you enter these gates.”

I dismissed her words, thinking, well, I don’t understand why I’m here—and I don’t want to be here! I was tired of visiting museums.

It’s easy to dismiss words, to not even hear them until you are confronted with their reality and then the words come back and scream at you, mocking your ignorance because now you are experiencing the words, seeing the horror with your eyes, feeling it slide under your flesh and invade your mind.

William W. Quinn, 7th US Army liberator of the prisoners said that “Dachau, 1933-1945, will stand for all time as one of history’s most gruesome symbols of inhumanity. There our troops found sights, sounds and stenches beyond belief, cruelties so enormous as to be incomprehensible to the normal mind. Dachau and death were synonymous.”

Was it “inhumanity” or was it an expression of the dark side of humanity, an expression of the evil that is as much a part of the human condition as is the good?

Himmel said, “Nature is cruel, therefore we are entitled to be cruel.” It was horrifying to think how easily we justified our brutality as being necessary or normal.

Nature isn’t cruel, it just is. But for humans with hearts and minds and dreams and agonies and hopes and fears to turn on other humans and make a conscious choice to hurt and kill them, how could it be? How was it possible that a good God could create something as twisted as this and allow it to continue? Dachau was one little stop on the long, tangled road of humanity. This behavior had happened endlessly, over and over, and it was happening still.

While I walked through Dachau with other tourists, all of us shaking our heads and muttering how can this be, new victims were being blown apart in Vietnam, a “righteous war,” or so our God-fearing leaders in America told us, justifying killing in the same way Hitler had justified it to his people and they had raised their voices as one and consented, sheep led to the slaughter, blind, unthinking. Dachau had ended, but the evil had moved someplace else. It never really went away, it just moved around, a slippery devil, a part of us all, impossible to catch and contain.

I saw all my nightmares that day, within the space of a few hours, walking through the gas chambers, the barracks, looking at the pictures of haunted faces and soulless eyes. That was the worst, the eyes, for it is by looking into the eyes that we connect with one another. I saw how a soul can be sucked right out of people, their eyes becoming empty haunted shells. Skeletal children stood before me, their ghosts crying waterless tears, empty piercing eyes, bodies broken, contorted, tormented, ancient spirits forever lost.

“It’s what happens when all hope is gone,” I heard a lady say next to me, staring at the same photos.

What is hope, I thought? Do I have hope? I must have it. My eyes don’t look like that. Hope! I have it and I must never lose it, or I will become like them. How many hundreds of thousands of girls and boys like me and my sister, and my brothers had walked through those gates just as my mom had said, scared, eyes wide open but still with hope, thinking, maybe I’ll be okay, I’ll be lucky, God will save me, it won’t be so bad, it’s just a summer camp, I’ll be home soon, I’ll be lucky, yes, I will…

Only to die in agony, prayers unheard and lost on the autumn winds, piled in graves like dead leaves to ferment and enrich the earth, anonymous, their bodies defiled, their worth reduced to bits of jewelry, gold fillings, hair, bones, piles of bones.

Bodies piled high, mountains of bodies, with men in suits casually surveying them, walking back and forth, discussing philosophical ideologies, doctors conducting experiments that would make any horror movie seem tame, and then the doctors and scientists, SS guards and officials receiving their pay checks for jobs well done, fulfilling their job descriptions, believing they were cleansing humanity, leading the master race towards a new world order, leading the chosen ones to heaven, going home to their families each night, kissing their children, eating a warm home-cooked supper, gorging themselves on food and pleasure, attending church on Sundays, and sleeping in beds of soft goose down, sleeping….did they sleep, their dreams sweet and untainted?

“Millions of Jews killed, but not just Jews,” the lady standing next to me said, reading the inscriptions. “Poles, gypsies, Russians, communists, homosexuals, the disabled and mentally ill, the intelligentsia, political activists, Jehovah witnesses, those who hid Jews, Trade Unionists, criminals, and anyone labeled an enemy of the state.”

“Why would they do this?” I whispered.

The answer came…the one I dreaded but knew was true: “They believed they were doing what was right.”

I don’t know who that lady was. I don’t know why she was there. She was a stranger to me who spoke English with an accent. I don’t remember what she looked like, but I remember what she said. A brief encounter between a child and a woman on the edge of hell, speaking of vile things that should never happen but that had happened anyway. And then we walked away from one another in opposite directions, never to meet again.

We encountered another lady as we walked through the barracks, although we didn't speak to her. She was shaking her head, saying over and over in German, as if trying to make it real in her own mind, “It was never as nice as this. Never as nice as this.”

Mom spoke German so she understood the woman. “She was a prisoner here,” she explained to us.

I looked at the beds, the room, everything bare and clean. What must it have looked like when it was filled with starving women awaiting death? The lady in front of us was old now, her shoulders bowed, her face twisted with the pain of remembrance. How was it possible to survive and ever feel even one moment of happiness, ever laugh again, ever tell a joke or listen to one, ever even be sane?

It was late afternoon when my family left that place. In silence I climbed back into the safety of our van and lay my head against the window. The air outside was cold and misty, covering the deep green forest with shiny, blinking dewdrops. Surely there was something sinister in the outward beauty of that forest. What horrors had happened beneath those trees? Perhaps in a moonlit glade, just like this one, a grave had been dug and people herded there, the crack of rifles splitting the air, their bodies falling one on top of the other and covered by earth, the green grass growing up and over the mound, beauty swallowing the terror. I felt as if we as humans didn’t belong, as if we were aliens on this planet. Without us, the natural world would thrive.

My body ached with tiredness. I wanted the van to stop. I wanted it to pull into our driveway in front of our house back in Woodland Hills, and for my parents to say, “We're home!”

Where would we stay this night? When, oh when, would the journey end?

Why couldn’t we at least be back at those other gates, the ones that had opened to us with such warmth and joy only a few days before. The gates of the Sisterhood of Mary, Evangelical nuns that some friends of my parents had told us we simply must visit.

Those gates had swung open and out came a woman dressed in a long gown with a white covering on her head. I blinked, thinking surely, I was dreaming. But she was still there, greeting us as we climbed out, saying “Welcome to the Sisterhood of Mary.”

The woman’s name was Mother Basilea Schlink and her face radiated sunshine on that dark night. Inside, the Mother House was lovely in its simplicity, with warm, inviting rooms for guests to stay in.

Mother Basilea had been called to start the sisterhood in 1949, after the war. During the war she had faced danger and had been interviewed twice by the Gestapo. The Mother House had been built with bricks salvaged from the wreckage of Darmstadt.

“We call it the Sisterhood of Mary after the mother of Jesus who followed him all the way to the cross,” said Sister Eulia, a young rosy-cheeked woman.

We were given a tour of the grounds, participated in services and we even contributed by singing together. That’s me looking very serious on the far right, then Mom, Janna, Dad and Davy. Not sure were the youngest, Jon, is. He probably refused to sing, ha-ha.

That night we ate a meal of savory soup, crusty bread, cheese and apples in a large dining hall with other guests, the sisters singing a prayer for us all. They sang and danced seemingly for no reason other than spontaneous joy. Bleary-eyed with fatigue, I wondered if I had entered an upside-down place where miracles were possible and preconceived notions were thrown away.

At the dinner table sat former Jewish prisoners of the concentration camps who were staying there, awaiting their time to testify in the trials of war criminals. But the sisters didn’t limit their kindness simply to those who deserved it. Not only did they open their home to the Jews, but they visited the Nazi prisoners, praying for their salvation.

Here is a quote from my mom’s journal:

The trials still continue and there are right now Jewish witnesses housed on Canaan who are there to testify. The sisters are always present at these trials to help these poor people, many of whom after all these years can scarcely speak of their experiences. Of the thousands in the particular camp from which this group came, only 47 survived. One man lived in a cupboard for 14 months, another in a hole in the ground. But they go as well to speak and sing to prisoners. This month Sister Eulia and Mother Basilea go to Poland…a land where every 7th male was killed by the Germans.

I was only ten, but I haven’t forgotten meeting these Holocaust survivors who had suffered so much. I sat there with them at dinner. I heard their stories. It was beyond what I could understand at the time, but I held it all in my heart. Then, after having seen Dachau for myself, I thought back to those old men, thinking, wow, they were there, they experienced it, they survived. I couldn’t imagine being that strong. That courageous.

I was sleepy, full of good food and lost in this otherworldly experience, sitting at that table surrounded by Jews and nuns and my parents and sister and brothers, thinking how miraculous it was that we were part of the same family. There was good, here at this table, and I was so thankful to have found it.

After dinner the sisters danced and sang all the guests down the candle-lit halls, dropping each of us off at our rooms with a blessing. Outside an angry storm raged, a deluge of rain beating upon the rooftops, while inside we were safe and warm and comfortable. It seemed that no danger could enter our secure fortress.

The next morning, as we said good-bye, Mother Basilea hugged me and prayed that God would bless me.

She cradled my face in both her hands and looked at me with sharp eyes. Certainly, she wasn’t physically beautiful. I wondered how old she was, older than my parents probably, but her skin was smooth without many lines. Her hair was thin and dully gray. Not beautiful. Majestic. She was majestic in my young eyes.

“You are an artist,” she said.

I nodded, tongue-tied.

She smiled brilliantly. “It is a gift from God. Use it well.”

I nodded again, still unable to speak for I was in such utter awe of her. How she had known I was an artist; I had no idea. No doubt my parents could have told her in the course of some conversation. It didn't matter. I'd been given a blessing and admonition all at once. Her words stayed with me, positive and powerful, a shield against the evils of what I would see and absorb into my spirit at Dachau. There was goodness and I could choose to be a part of it. This I remembered long after the image of Mother Basilica's eyes and her smile had faded.

My family had been subdued and thoughtful, in a peaceful sort of way, while staying with the sisters. Driving away the spell lifted and we felt a bit like Moses descending from the mountain, back into ordinary society where cruelty and violence were an everyday occurrence.

“Okay, those ladies were weird,” said Janna. “But nice,” she acknowledged. “Amazingly nice.”

I agreed. Weird was a good word. I loved the word “weird.” It covered so much territory. That's what I would do when I wondered about things. Just conclude that everything was weird and leave it at that. Of course, such thoughts were accompanied by a desperation. My brain didn't allow me to happily conclude that the world was simply “weird” and leave it at that. Not after Dachau.

As we drove away from Dachau, along another bumpy, winding road, Janna announced, “I’m going to knit another bear.” This was something we did to make the time go by.

I groaned. I wasn’t good at knitting. But what else was there to do. It was strangely therapeutic to knit, just do something practical that didn’t require deep thought. Keep my hands busy so my brain didn’t need to think too hard.

I look back now and think of all the people I encountered on our travels. Because I spoke with eyewitnesses I know the truth of the Holocaust. All I can do, as with others, is to pass on those stories and pray that there are enough of us telling them to counterbalance the lies. Because the further we get from those times, and the more the algorithms that now determine “truth” push lies upon us, the more ignorant people will be about the very heart of what makes us human, about what gives us the strength and the courage to rise above hatred and choose courage and truth.

18 years ago, my then 13-yo daughter was critically ill and spent 63 days in the ICU. At a follow-up appointment with the neuro-opthamologist to determine how the illness impacted her vision, I was asked by a woman in the waiting room about my daughter's situation, which included medical trauma. This incredible woman, Jaffa Munk, came and put her hand on my daughter's arm and said "Molly, I was in the concentration camps, I lost my father, my mother, my whole family. They took everything, but they couldn't take my spirit. Whatever they do, whatever happens, they can't take your spirit, always remember that."

That profound message had a huge impact on my daughter and me, too, and definitely helped my daughter maintain perspective about her situation.

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn507547

Beautifully written! I'm Jewish and decided I wanted to go to Auschwitz. It is seared on my brain. I still have nightmares about it. I can't imagine how anyone survived that horror. The Holocaust deniers are damaged individuals with whom I refuse to engage. Also in this day and age some ppl will say anything for attention. We must never forget what happened and posts like yours remind us in a way that is both brutally honest yet uplifting. Thanks for posting. Sabrinalabow.substack.com