Reflections for a Sunday: That Time My Family Smuggled Bibles

"You can’t understand. It’s a different world we live in. The secret police are everywhere. Please never say my name. What we have in our country is the same as in Germany under Hitler.” 1967

"You can’t understand. It’s a different world we live in. The secret police are everywhere. Please never say my name. What we have in our country is the same as in Germany under Hitler.” From a conversation my parents had with a young intellectual from behind the Iron Curtain, 1967.

One-time or recurring donations can be made at Ko-Fi

You can listen to me read this essay here:

This beautiful Sunday I thought I would share one of the many stories I have from my incredible childhood experiences. I wrote a little bit about it quite a while ago in How to Become a Domestic Terrorist, and since I have so many new subscribers since then, I think you will all enjoy it.

In 1967, my family did a crazy thing. We smuggled Bibles into Romania. This was a serious crime. My parents could have been imprisoned for it. At the age of eleven, I had firsthand experience of what it felt like, as an insignificant nobody, to defy the full power of a totalitarian regime.

We drove around in a bright red VW van; you can see it below. I am next to my mom, my dad behind, then my younger brother, Jon, the eldest, David, and my older sister, Janna.

When my family braced itself to enter what was then known as the Iron Curtain, we knew exactly who we were and why we did it. We were God’s servants standing against the forces of Satan. The Bibles we carried were precious and worth the danger of bringing them to my dad’s contact.

Okay, I say we all understood this, but to be honest, I didn’t, not really. I had no idea what it meant to be that serious about anything. To not just talk about convictions but to go to so much trouble to live them.

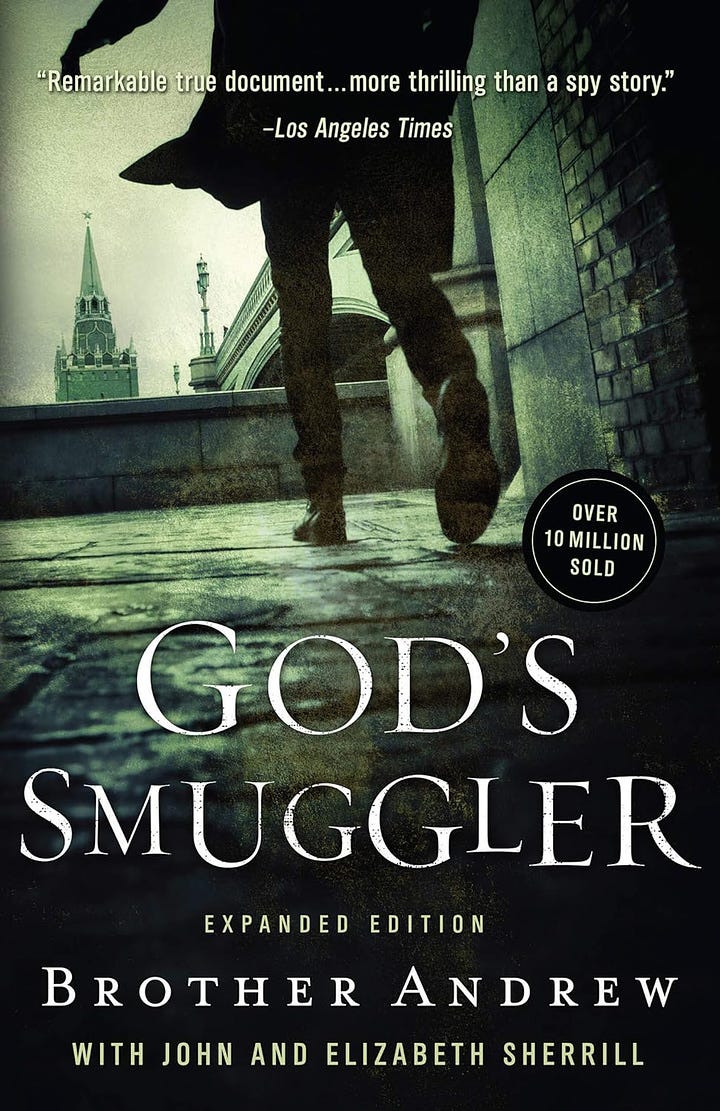

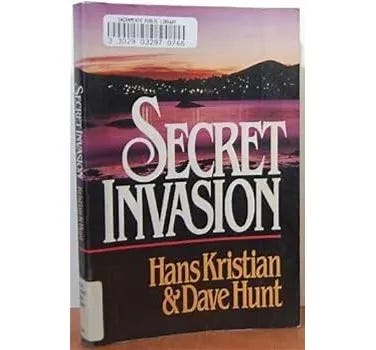

I’ve written about this previously, saying it was Brother Andrew who gave us the Bibles, but I realize now it could have been Hans Kristian, since Dad knew both of them. My mom wrote nothing about it in her journal, I suppose out of caution to protect whichever one it was since smuggling Bibles was dangerous. At that time, both men were well known for their Bible smuggling ministries.

Whichever one it was that inspired my dad, I remember Dad talking warmly about how they had a lot in common, joking that they both loved adventure. In fact, they’d both dreamed of being spies in their youth. Dad had even studied Russian at university.

So, however it happened, we found ourselves embarking on our dangerous mission in June of 1967. This was shortly after our escape out of Egypt, days before the outbreak of the 6 Day War.

“They’re in the brown suitcase.” Dad pointed to a nondescript suitcase that looked like it had seen better days. “At every border crossing we’ll pray, and God will answer our prayers. This is a wonderful opportunity to learn to trust in Him.”

Dad patted the drab and well-used suitcase, packed into the middle of all the others. He gave each of us kids a good, long stare. “See? Here it is, plain as day. We aren’t actually smuggling anything. But just to be on the safe side, don’t talk about the Bibles or the suitcase, not even in our hotel rooms. Understand?”

I nodded my head along with everyone else when, in fact, I wanted to scream, that’s not making me feel any better, saying we’re not smuggling and then telling us we can’t talk about the Bibles—not even in private!

As we approached the first border crossing into Bulgaria, Dad stopped the car and prayed, just as he said he would, that the Lord would blind the eyes of the guards. This became a ritual before each crossing and checkpoint. Once, when we unexpectedly arrived at a surprise checkpoint, my dad actually backed the car up and parked so he could pray. Surely this looked suspicious, I thought. But we made it through without difficulty.

Each time we successfully passed a border or a checkpoint, relief drenched me in an exaggerated feeling of well-being. It was great to be alive, it was great to be here, I loved this country, I would never doubt again. Glory hallelujah!

All thought of how much I wished the Bibles would disappear was forgotten as I surveyed our beautiful surroundings, pleasantly surprised to see that the communist countryside was as lovely as any place we had been in the West, with forests just as lush and green, fields covered in wildflowers, and friendly people, the women dressed in long skirts and kerchiefs.

Once we reached the towns, we began to see reminders of the people's “liberation” with the ever-present monument to the Soviet Soldier. We came to expect the many check points where we had to show our papers, or sometimes simply a man standing on a street corner who jotted down our license plate and time of passing. In every hotel and even in private homes, we were automatically registered with the police.

In my mom’s journal, she describes a conversation we had with a college student we met.

“There is no liberty in my country,” he said. “America, yes.” He claimed that 90% of the people listened to Voice of America, including the communists. After his education was completed, he would be sent to a village to work for a few years. Then, if he was lucky, he might get permission to return to the city.

At the Hungarian border, Mom records that even the lining in her purse was ripped out. She approached a car with Czech license plates and asked in German what they were looking for. They did not reply. She persisted, in German, “Do they think someone might be trying to escape this ‘Wunderschones Land der Freiheit?’ Quietly came the reply, ‘Das ist recht, das ist recht.’

My parents were very brave. Me, not so much. I suffered such anxiety at those crossings.

Another Czech contact confirmed the same oppression there. To ‘escape’ would mean retribution on their families. When Dad asked if there wasn’t something people could do to change this, the reply was, “The people are nothing. There is no hope. All is propaganda. At the beginning, people believed their promises but no more.”

The state blamed everything on America, the poverty, everything that went wrong. A young man from the Soviet Union told us he was at a trade fair conference and managed to hide two Life Magazines under his shirt and take them home. “Couldn’t you go into the American Embassy and read the magazines?” my parents asked. “No, the police have a building on both sides, and they take photographs of everyone who goes in. You can’t understand. It’s a different world we live in. In the days of Stalin, no family could trust its members. No one dared to speak. Normal relations were shattered. There were 20 million in Siberia. 5 million of them were killed. It is better now but still horrible. The secret police are everywhere. Please never say my name. What we have in our country is the same as in Germany under Hitler.”

These were just some of our experiences conversing with people who were brave enough to speak with us.

As we neared the border crossing into Romania, my fears grew in magnitude. The dour guards made the familiar and dreaded demand that we all get out. They searched our van from top to bottom and as they did, I became increasingly nervous. My stomach was in knots, and it took all my self-control not to throw up.

Just look normal, I kept telling myself.

Normal?

They brought a special device to check in the tires, for what, I couldn’t imagine. Then came the worst moment, the moment we always dreaded. Dad was commanded to open the back of the van. He did.

The guard motioned for my dad to take out all of our luggage. Then, to my intense horror, the guard proceeded to systematically open each one.

That was it. I knew I was going to die. I looked at my older sister, Janna. She didn’t look back but continued to watch bravely as the guard threw clothes onto the ground.

Then, the worst thing happened. My younger brother Jon, who was only eight, ran up to Dad and demanded in his loudest voice, “Did he look in the brown suitcase yet?”

We all froze.

The guard stopped his searching. “Brown suitcase?”

He then turned to the pile of suitcases and reached down to pull one out. That moment of reaching was an eternity. And then, it was all I could not to cry out in relief. He had grabbed the other brown suitcase, the one that didn’t have Bibles. He proceeded to inspect every item in the suitcase before discarding it in disgust.

The guard nodded at us to put the suitcases back and we hurried to clean up the mess and replace them. Nobody said a word until we were through the checkpoint and into Romania.

Then, the interior of the van erupted into whoops of happiness and relief. We had made it into the country where Dad would meet his contact. We didn’t have to cross any more borders. Looking back, truly it was a miracle that not once at any of the border crossings did a guard look in that brown suitcase, even though, at some point, they had looked in all of the others.

Romania seemed somehow drearier and more oppressive than the other countries. Mom commented that the people were the dourest we had ever encountered. The fact that the sunny skies grew dark with rain might have influenced our perception. The rain quickly turned into a driving thunderstorm and Dad carefully navigated the slippery road, where we saw a terrible accident, a truck that had crashed over a steep embankment. Passing through the villages we noticed the houses were all set in perfectly symmetrical rows, each front richly carved and painted, while the other sides were drab and bare. It was like a creepy movie set, not real somehow.

The deeper we progressed into the country, the more oppressive the atmosphere grew. It was horrible to think that these people lived like this every day of their lives. They could never fully trust their friends and family. At any moment, they might be betrayed by someone who claimed to love them.

Late one night, we finally found a private home to stay near to Count Dracula’s castle. We hadn’t eaten any supper and the couple made us some tea. Mom passed out pieces of Swiss chocolate and I miserably thought that I just might die of starvation.

Appropriately, the next day we visited the castle of Vlad Tepes, of Count Dracula fame, imagining the thousands of stakes driven into the ground and the bodies impaled upon them. Vlad might have inspired modern stories of vampires, but to the people of this land he was a hero who had fought for their independence from the Turks. One person’s hell can well be another’s heaven.

“And then, everything’s so beautiful,” I said.

“Yeah, but in a devil way,” said Janna, her green eyes large and hypnotic. “Just watch out for vampires. They’re here, I can feel it.”

I shivered. My sister loved to frighten me. She was such a good storyteller, and I was such a good listener.

The legends of Count Dracula cast a spell upon us as we drove through the Carpathian Alps, the forests forbidding and mysterious, the grassy valleys so shining green it almost hurt my eyes to look at them.

At one point, Ceausescu happened to be making a tour through the towns and villages just as we were heading through the countryside, along a narrow road. He and his entourage were right in front of us, and it was slow going, as traffic was held back. Each village we entered, we saw evidence of the great leader’s passage, flowers trampled in the streets, banners hanging in disarray, the decorations on houses being removed. We continually arrived at the end of the show. Nowhere did we see signs of joy or continued festivities. It was an eerie feeling.

At last, we made it to Bucharest. We drove in dreaded silence along the wide empty boulevards past Palace Square. I pressed my face against the glass of the car window, looking out at the austere, authoritarian buildings made of cold stone.

We all know now what would happen to Ceausescu. But in those days, the powerful couple basked in glory, with no premonition that one day their greed and corruption would unleash a bloody revolution and they would die in disgrace.

Those future events were but whispers beneath the surface. All seemed solid and built to last forever. Monuments of vengeful soldiers towered over us, celebrating the Glorious Deliverance. We passed few cars on the wide avenues or pedestrians on the sidewalks. It was all so foreboding, so constrictive, making me feel as if I could not breathe but there was no obvious illness or object blocking my airways. This was a futuristic city straight out of a dystopian novel, but it was right now, right here.

This was where Dad would meet his contact and it seemed fitting that it should be such a soulless and imposing metropolis.

Dad had memorized the street number of his contact as it was too dangerous to have anything written down. We’d been warned that a journalist had written an article in an American magazine about a Christian leader’s activities here without naming him, but it hadn’t mattered. The man had been picked up and had disappeared. We did not want to put Dad’s contact’s life at risk.

My parents had asked on several occasions for a map of the city and found that there were no maps available to tourists. In fact, our asking was treated with suspicion, as if we must be planning some kind of covert operation. Which I guess we were. Several times Dad got out of the car to seek help from pedestrians. Each of them looked shocked at being approached, darting furtive looks left and right as they scurried silently on. One or two paused long enough to give short, mumbled responses that meant nothing to us, before rushing away. We had never encountered such fear from the people as we did in Romania.

We began to feel desperate. Because the streets were so empty of vehicles, we stood out as if we were under a spotlight on center stage. We might as well have had neon lights flashing on our van and a loudspeaker blaring: Subversive activity happening here; come and arrest us! We didn’t dare keep driving around and around, attracting attention to ourselves.

Finally, I don’t remember how, we found the drop off location, the streetlamps casting a pale light in the falling rain. We watched with trepidation as Dad walked down the sidewalk, the brown suitcase in hand. Perhaps it would be the last time I’d ever see my father. I imprinted an image in my brain of him disappearing into the gloom of the night, hunched over in the interminable rain, his coat slick with water, that horrible brown suitcase held tightly in his hand. Then Mom drove us off for some “sightseeing,” which was a joke since it was now a miserable, rainy night and there was nothing much to see anyway.

Tears stung my eyes. I was angry with my dad for doing such a crazy thing. He didn’t need to. It was just one suitcase of Bibles. How could it possibly make a difference anyway? What would happen if my dad disappeared? Our family couldn’t survive without him.

We came back an hour later to find Dad waiting for us. I was so relieved; I didn’t immediately realize that he was still holding the suitcase. Anxiety emanated from my dad, but no one dared ask why he still had the suitcase. He put it back in the car, climbed into the driver’s seat and took off, looking this way and that.

“No one was there,” he said tersely. “I hope no one was following me.”

He would say nothing more.

Once we returned to Austria, we discovered that just days before our arrival in Romania, my dad’s contact had been bought out of the country for $7,000. This man had been a pastor and the director of a Romanian seminary. When the communists took over, he'd been demoted to janitor. The teachers at the seminary had been fired, some of them imprisoned. They'd been replaced by government workers who had tormented and abused the newly appointed janitor on a daily basis. The situation had become increasingly dangerous for him.

As we drove away, we knew none of this. After all, there were no cell phones in those days, no internet. For all we knew, the pastor had been imprisoned. For all we knew, we would be next.

I should have been concerned about the pastor. Instead, all I could think of was that we were still stuck with the blasted Bibles. So much for God’s will! We'd traveled such a long distance, braved so many searches and interrogations. It was like God was playing a joke on us. Why would he do that?

I can’t think of many experiences in my life that were more disappointing and terrifying than that night in Bucharest.

Now, my dad had to come up with a new plan of how to dispose of the Bibles. We had some other contacts we could give some to. For the rest, he decided that we would hand them out randomly to people who might want them. God would lead us to the right people. I hated this idea, but of course I couldn’t object. Honestly, I wished we could just ditch them by the side of the road.

Once my dad had a plan of action, his spirits rallied. “This must have been God’s will all along,” he said. “We can’t see the big picture. But God can. He knows exactly where these Bibles need to be.”

Handing out the Bibles opened doors to a world we wouldn’t have otherwise seen. One old man cried when we gave him a Bible. He didn't speak English, but he didn’t need to. Words weren't necessary to convey his feelings of gratitude and joy. A young man, an intellectual who wasn't a Christian, took a Bible out of curiosity. He promised to read it when he got to the countryside where he was being sent to work on a farm.

Another family led us to a secret meeting place, and we joined a worship service. When we revealed the Bibles, it was as if we had opened a treasure chest of gold and jewels. We were invited to the home of the pastor and shared a meal with his family. These families lived in drab apartment buildings, in dark, tiny spaces, yet they seemed so happy and thankful of every little joy that came their way.

My dad decided to give the rest of the Bibles to the pastor of that church. At last, the Bibles were gone. That horrible brown suitcase was empty.

We were relieved to make it into Yugoslavia, a place that seemed much freer than the other communist countries we had visited. I loved Yugoslavia. I never would have guessed back then that I would end up married to a Slovenian pop star and living in communist Yugoslavia in the 1980s.

Once we made it to Austria that sense of freedom was magnified. I had witnessed with my own eyes the oppression, the heaviness of totalitarian regimes. The fear they imposed. And I had seen the joy in people’s eyes as we gave them Bibles. I couldn’t imagine living in a place where I couldn’t read what I wanted.

American had its problems in those days, but nothing like Romania. At least in America, if you didn’t agree with something you could stand up and say so. You could even make fun of the president if you wanted to. I never dreamed I would see what I am witnessing in America today.

I will not forget one young man ’s response to my dad, when he told the young man how popular communism was with American youth. He became very angry and distressed.

“They are fools. They are insane. Let them come and live in my country. This should be the post graduate course of every American student. America has not done what it was supposed to do. Roosevelt believed Stalin. It was America who allowed communism to take over in Europe.”

He could have been talking to the youth at these protests on campuses right now. Go and live under Sharia Law. Go to Sanaa University, where the Yemeni based Houthi terrorist organization has offered places for protesting students.

I can tell you with certainty, the Houthis are mocking us when they announce they will “welcome students suspended from US universities” over their involvement in anti-Israel protests.

What do you think. Will the gender fluid youth below who are demanding to be called by their chosen pronouns fit in well at the Houthis university?

One day, we in American will understand the long-term consequences of our actions. I just pray it won’t be too late. America isn’t perfect, but the fact youth can even protest proves how free it still is. Be thankful and don’t spit on that freedom.

Traveling behind the Iron Curtain—and that was a very good name for it—was a terrifying experience for me. At the time, I resented my parents for taking us there. I didn’t understand why it was so important to them. But then I saw the faces of those who received the Bibles and I felt ashamed. I still didn’t understand completely. It would take growing up and looking back to do that.

Of course, my experiences were unusual. Most kids do not have parents like I had. I’m so thankful they were my parents. Now, I have something I can do with those experiences. I can share them with others. Life has a funny way of working out in unexpected ways, and that is one of the reasons why I keep my hope for the future. I pray people listen and please, if you know any young people, share these stories with them.

"Roosevelt believed Stalin. It was America who allowed communism to take over in Europe.”

Every single Czech person knows this to be true. Patton's army was 60 miles west of Prague in the town of Plzen (Pilsen in English - yes, that's where the ORIGINAL beer comes from) His advance reconnaissance units were on the outskirts of Prague. Truman caved to Stalin's demands and Eisenhower ordered Patton to retreat back to the German border. A similar situation existed in Poland where the British were adamant about pushing the Red Army out but by March/April 1945 it was too late. Because Czechoslovakia had been in the western orbit prior to WW2, we were allowed three extra years of freedom. The official communist coup d'etat didn't take place until 1948.

Romania was a horrible dump. We traveled through there in 1963 on a trip to the Black Sea in Bulgaria (which was very nice for a 10 year old boy who had never seen an ocean) Romania is the scariest place I've ever been to. I'm told it's somewhat improved - just a tad. Please read the book "The Un-humans" about the communist takeover of Romania. The horror will stay with you for weeks.

Your father was a MENSCH! Bless his soul 🙏❤️

excellent story

Thank you so much for sharing.

One day, this could be our country!