Listening to Monsters

Monsters all have sad stories to tell. But be warned, monsters are still monsters and given half a chance, they will kill you too.

You can listen to me read this essay here:

One-time or recurring donations can be made at Ko-Fi

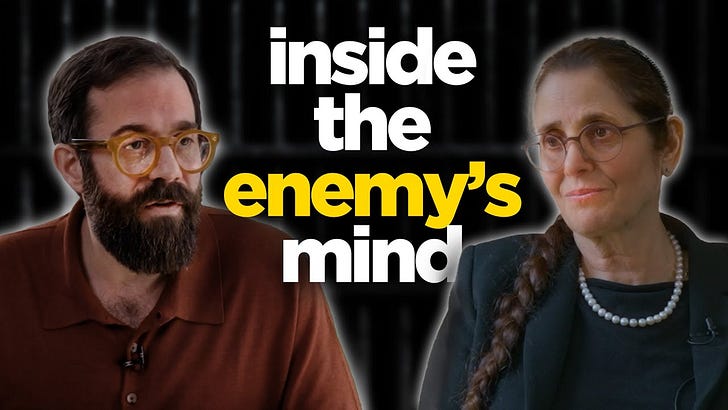

Jonathan Sacerdoti became one of my heroes during the Oxford debate, which I wrote about in Is Israel a Genocidal Apartheid State? Since then, I’ve tried to watch as many of his interviews as possible. When I found out he was interviewing Israeli criminologist Dr. Anat Berko, I absolutely had to watch it—and it does not disappoint!

As the introduction describes:

Dr. Berko has interviewed countless terrorists. As Israel releases convicted terrorists in return for hostages held in Gaza, she describes who they are and what they did. With her deep knowledge of Palestinian and Arab culture, she explains the background to the attacks and the religious and social motivations of the various categories of criminals, including women and children.

About Dr Berko: Dr. Anat Berko is a world-renowned expert on counterterrorism and policy maker whose research focuses on suicide bombers and their handlers. Berko is a former member of the Israeli Knesset and Lieutenant Colonel (ret.), Israel Defense Forces. She is the author of two books and numerous articles on terrorism and government policy in confronting terror.

Dr. Berko is the mother of

and I encourage you to follow her and subscribe to her Substack.For me, there was added interest in this interview since I devoted ten years of my life to teaching creative writing to High-Risk Offenders (HROs), youth facing life sentences for the most serious crimes. I co-founded InsideOUT Writers, a creative writing program for incarcerated youth, teaching in all three Los Angeles County juvenile halls, many of the camps, and other placement facilities. At the writing table, I encouraged youth to explore the stories of their lives, breaking barriers with others at the writing table who might have been enemies on the street. Through this process they were able to take all the jumbled thoughts in their heads, organizing them like pieces of a puzzle on page after page, making some sense out of how the abused becomes the abuser.

I recognize much of what Dr. Berko talks about with Hamas in the hierarchy of gangs. How, as she says, “everyone has their jobs”, and leaders such as Yahya Sinwar do not send their own children to blow themselves up. It is children of poorer families who are most taken advantage of, growing up knowing only abuse, violence, bitterness and hate. They become the foot soldiers, the ones who are sacrificed first in whatever war those in power decide to carry out.

In 1997, I met Casey Kaddish Cohen, one of the foremost authorities on the death penalty phase in California. It was Sister Janet Harris, the other founder of InsideOUT Writers, who introduced me to him. From the minute we met, we had an immediate connection. We became best friends; he was the person I trusted more than anyone else in the world, my confidant and mentor, until his death three years later from cancer.

Casey worked on many of the most notorious murder trials in California. Leslie H. Abramson, who represented the Menendez brothers, said of Casey that when she talked to her clients, she got virtually nothing, while “when he sat down with them, all this stuff came out.”

Casey and I spent as much time as we could together, discussing philosophy, morality, his cases, my cases, he taught me how to interview the girls in my writing classes. He took a special interest in Silvia Sanchez’s case, the girl who became a close friend of mine over the years and would go on to spend twenty-five years in prison for a murder committed by her older, abusive boyfriend,

Shortly before his death in 2000, Casey asked me to visit California Death Row inmate Maureen “Mikki” McDermott, a woman whose habeas appeal he had worked on and who he believed was innocent. He felt he had failed her somehow.

That was how I found myself fulfilling my promise to him years later, heading to Central California Women’s Facility to spend many hours speaking with Mikki.

With that introduction, please watch the interview with Dr. Berko.

Below that, you can find out more about Casey and Mikki.

I met a murderer once. Or at least, someone who had been convicted of murder. Because truth is never easy to discern and whoever tells the best story usually wins, regardless of whether it’s true or not.

It’s been many years since I sat across the table from California death row inmate Maureen “Mikki” McDermott. I did this on two occasions, traveling up from Los Angeles to Chowchilla Women’s Prison, spending a total of approximately 5 hours each time with her.

Her case is especially interesting now as one of Donald Trump’s first orders as president was to compel the Justice Department to restart federal executions, which have been on hold since a moratorium was imposed in 2021.

Mikki’s latest habeas appeal was denied in 2023. She is now 79 years old. If she is executed for the April 28,1985 murder, she will be the first woman to face the gas chamber in California since 1962 and will be the fifth woman put to death by the state.

The Crime

Back in June of 1990, Mikki, a registered nurse, had been sentenced to death for a particularly heinous and callous crime.

As the story goes, five years earlier, Mikki had hired a hospital orderly, Jimmy Luna, to murder her roommate, Stephen Eldridge, so she could collect a $100,000 mortgage insurance policy. Stephen, co-owner of the house where they lived together, was stabbed 44 times and his penis cut off by Luna. Mikki and Stephen were both gay and this was made much of in the trial, which took place in 1985 at the height of the AIDS scare. Luna claimed Mikki had ordered him to cut off the penis so the police would think it was a crime committed by a crazed lover or a homophobe.

So why had I gone to visit a monster like Mikki?

It was in 1997 that I met private investigator Casey Cohen. At that time, I was president of InsideOUT Writers, a creative writing program for incarcerated youth that I had founded with then Catholic Chaplain of Central Juvenile Hall, Sister Janet Harris. The youth I worked with were kids who were facing life sentences for serious crimes.

It was Janet who had introduced me to Casey. I used to joke when I walked through the grounds of CJH, the Catholic nun on one side of me and the atheist Jew on the other side, that I was perfectly balanced. Those were great days, but they didn’t last. Nuns can be do-gooders and have a darker side, too. She tried to destroy my life so she could take all the glory for founding InsideOUT Writers. The underbelly of the nonprofit world isn’t very nice. But that’s a story for another day.

Casey’s real name was Kaddish, meaning in Hebrew “a prayer for the dying.” He often spoke of his name ruefully, as if it was a kind of curse given to him by his father who hadn’t been religious but had bowed to the power of tradition. With Casey’s thick beard and soulful brown eyes, he was like a father confessor and witnesses and criminals alike found themselves confessing their deepest and darkest secrets.

At the time I met him, Casey had the reputation as one of the foremost authorities on the death penalty phase. He was usually hired by the defense during the habeas appeal to help uncover stories from the murder’s past in order to humanize them so that they could escape the death penalty for life in prison.

Casey had worked on some of the most notorious murder trials in the country, all the way back to the tragic murder involving Marlon Brando’s son, Christian Brando. He was a favorite of famed criminal attorney Leslie Abramson, and his last job involved her client, 18-year-old Jeremy Stromeyer. On May 25, 1997, at 3:47 am, Jeremy followed 7-year-old Sherrice Iverson into the bathroom of a Nevada casino and molested and killed her, twisting her neck to make sure she was dead, just like he’d seen on TV.

You’re probably thinking as you read this, what a morbid world, how did you end up there? That’s a longer story than I have room to tell here, but suffice it to say, it was a world that interested me. After all, I was working with incarcerated youth who were facing life sentences for serious crimes. From Casey, I learned how better to talk to the girls who were in my first writing group and how to help them share their stories.

“Everybody reads about Jeremy, but no one comes to know Jeremy the way I do,” Casey told me during those days before the trial. “No one else hears him speak those barely audible words. And then I have the responsibility of interpreting it all so the attorney can go into the courtroom like into the lion’s den, and fight for their client’s life. People may think they don’t deserve saving, but when it comes to the courtroom, it isn’t a moral issue. It’s about honesty and fairness. Well, it should be. But most often it’s about power and political careers. If you can beat them at their own game, now that’s a victory.”

Over the course of his career, Casey had traveled the world in search of those stories. He’d gone anywhere and everywhere, down some dark alley in Chinatown, or across the world to some mountainous village, interviewing the friends and families of convicted murders. He complained that the stories came to fill him like poison.

Hearing Casey talk about the stories as poison caused me great sadness. From the first time I met him, at a little Mexican restaurant not far from the downtown courthouse, frequented by lawyers, detectives and judges, I’d found out he was dying of cancer. I would know him for only three years.

When Casey wasn’t working on murder trials, he worked with Charlie English, known at that time as “attorney to the stars,” handling damage control with the likes of Tommy Lee when he got in trouble for allegedly abusing Pamela Andersen; or Robert Downey Jr. when he was picked up for drug or alcohol related charges, in the days before he turned his life around. Casey’s job was fascinating and dangerous, inhabited by a host of characters more colorful than any movie, with him the most colorful of all.

But it was Mikki’s case that troubled Casey until the very end. He was sure she had been innocent. He talked about it often and I came to know the case very well. I never questioned Casey’s assessment. After all, he was the expert, not me, and highly regarded in the field by his peers. Even the BBC had taken notice, doing a segment on his life for their Everyman series.

Casey had worked on Mikki’s habeas appeal with attorney Verna Wefald. They had done their best, but her appeal had been denied. He couldn’t bear the thought of Mikki sitting in a sterile room on death row, day after day, year after year, never being free again. Never traveling to far off lands, as she had hoped to do.

So, he started writing her letters. Only they weren’t ordinary letters. They were the most fantastical letters you could ever imagine. Within the pages of the letters, Casey created an imaginary world, inhabited by wild and wonderful characters. Casey wrote as if he were one of those characters, calling himself C. and her M. Each letter talked as if he was in some exotic location, Paris, Rome, San Franscisco during the 60s, a tropical island, running into old flames and dangerous acquaintances, attending wild parties.

None of it was true. But it was true within the world of the letters and when I read them, I was transported into that world and saw it all. I thought of Mikki receiving the letters, taking them out of the envelope, settling on her bunk, and sailing away on a ship of imagination. Away, away, from the purgatory of waiting, waiting for death.

Here is a little taste of one of the letters:

Dear M.

Do you remember the endless days and nights of heat and the painful summer we spent in Brazil (before you ran off with Bobbi Havana)? I can still see the room we rented, the large window overlooking the river. I dreamed about that time last night and it was like we were there again. I felt the tropical air. I saw the restaurant we would walk to down the dark, tree-lined path that led from our back yard. I heard the music and saw the lights of the town and the colorful, slow moving boats dancing on the water. In all my previous letters, in all my recriminations and complaints about your friends, I never mentioned, nor did I think, about that time or of Bobbi. What brought this up?

I can't say where I've been recently, but for five days I was trapped (depressed and lonely without you) in a cabin in a very remote park. Night after night I sat up, propped against the pillows, listening to the hissing rain on the trees just outside my open window. One night I must have been drifting off to sleep when I was startled by a sudden flash of strobe-like lightening and a loud reverberating thunder that seemed to go on forever. When I was fully awake I saw a living black stripe on the wall opposite the bed. When I walked closer it turned out to be a column of ants seemingly stirred by the heat and humidity, crossing horizontally from the window to a crack in the wall on the other side of the room. The column was fully four inches wide and at least 12 feet long. Eventually, the weather let up and in that brief time I walked outside just as a full moon came into view through an opening in the clouds, which were moving quickly across the sky. Then more lightening, rolling volleys of thunder and rain even more relentless than before.

I came inside and picked up a book of poetry which had been unread since I stuffed it into a compartment of my suitcase weeks earlier before I left Malaysia. Here was what it said on the page that fell open:

Do not think

after the clouds have vanished away,

“How bright it has become!”

For in the sky, all the while,

The moon of dawn.

At that moment I realized what a fool I had been not to see my M., the M. I had known, the M. I had traveled with in Europe (during that golden age). I realized I didn't know you then and that just possibly it was why you ran off with the likes of that aged, disgusting Artur, who I later learned was a unit leader in the Hitler Youth. And it explains why the Bobbi Havana episode.

Now I know why your tears fell like raindrops and why that melancholy air after the fun stopped. I understand why you needed people and why you threw yourself into planning parties with such intensity. That night the clouds parted, I understood the brightness that was hidden all that time. I know I was miserable to be with much of the time. And there were many occasions you had to take care of me.

Madrid, for example. New Year's Eve. A closet-sized room, confined to a squalid little bed, shivering and coughing. A small light bulb hanging overhead from a wire. And despite the fatigue, the apprehension and depression, lacking the will to stand and turn off that light, listening to the Christmas music on the street below, hungry, shabby, unshaven. And eventually a deep sleep in which I dreamed of “our” beach in Mexico. Bright, hot sunshine. Dos Equis on ice. Tanned bodies. No longer racked by coughing spasms. Young again. Healthy. Do you remember my white suit? Do you remember the night you took my hand and led me on to the open dance floor? My dream didn't last long.

When the door burst open, you were there with Mario, (our bartender friend from Barcelona). You had run into him on the street and somehow located me. I can still see the shock on your face. But what a joy it was. My misery instantly turned to hope. My self-pity erased. My survival assured. And because of you, M. The way you washed my face and dressed me. And then you and Mario helping me down the stairs and into a waiting taxi. And before I knew it we were at Fatumbi's villa. Fatumbi (“reborn”), how appropriate. Is it any wonder I can't abandon you no matter what?

Now, some sad news. Fatumbi is dead. Yes, he was in his 90's. No one knows for sure. He was so vibrant, alive, interested in the world until the end. He was the only European to penetrate the Yoruba society and learn their language. I heard he was even a “priest” in Africa where he learned voodoo. They said he was a babalao, a father of secrets. What secrets he must have taken with him. We were so lucky to have known him and learned from him.

Enough for now, M. I will no longer have a sarcastic tone when I refer to you as the Jewel of Paris. I will no longer refer to your wardrobe as “tres tackeee.” I will send you postcards from my destinations. And who knows. There is still our Paris, our Barcelona, our songs, our true friends. And, as always, you are in my thoughts.

M., if you know how to get in touch with Danielle, the one whose mother let us use her house when we flew to the Cote d'Azure, please let me know. Raphael Limon (sourpuss) asked me to locate her.

Forever, C.

Perhaps you can see now why I considered Casey’s gift to me of the letters as beyond any price. Shortly before his death, he sent copies of the letters to me, asking me to write about them and to visit Mikki if I could.

I began to research the letters. I found that reality was mixed with fiction. When he spoke of illness or special places, of C being abandoned, they were subtle hints of things that had really happened. He was ill, he had been abandoned and alone in far off hotel rooms, interviewing some criminal or family member of a murderer. In the letters M nurses him back to health, just as Mikki was a nurse.

When I discovered that Fatumbi, “Reborn,” was a real person named Pierre Verger, I started writing about all of it. Casey had told me many times about how he hoped I would tell the story. But what story? Was Mikki innocent or not? Where did the reality of her life end and the fantasy begin? How could we ever know.

This is a topic that came to haunt me, and it is something that explains my interest in AI and how we are being drawn further and further away from reality and into fantastical worlds created by AI. How will we know at some point which are our thoughts, and which are the thoughts of AI, as if takes over more and more of our thoughts. If a story is told well enough, does that make it truer than the truth, which might not be as pleasant to hear?

Somehow Casey, like Dr. Berko, was able to face monsters and listen to their stories, learning who they were beyond the one moment of their terrible crimes, absorbing their horrors and their tragedies and making sense of them. They were able to get to the truth without judgment. Hearing about someone in the media is very different from sitting with them face to face.

This is what I learned from Casey. Once he heard the stories, he wrote them down and turned them over to lawyers and prosecutors, judges and courts for them to decide the fate of the monsters who had shared their lives with him.

Casey absorbed the lives of hundreds of murderers into his spirit, and then, he let them go. But not Mikki. For whatever reason, he took her story and turned it into something totally make-believe. That he would write such a richly detailed series of letters to a woman on death row to make her life more palatable, surely, she must be innocent, I thought.

And so, when I finally managed to make that trip to visit Mikki, you can imagine how great my expectations where. It hadn’t been an easy process to get to see her. I had to write to her and ask her permission. We wrote back and forth a few times. She was suspicious. The press had been cruel, and a horrible TV movie had been made about her crime. But I was a friend of Casey’s and so she agreed to see me.

That was how I found myself sitting in a tiny room, across the table from Mikki, a big glass window on one side with a burly guard outside. She was a small woman, so ordinary, it was hard to imagine her plotting such a devious, horrific murder and then convincing a madman to carry it out.

She suggested I buy some food from the machines, so that’s what I did first. Eating our snack, we talked about her life on death row, she told me about the other women, many of whom were there for killing abusive partners or their own children. She told me how she only got out once a day for a short period, to walk around and around a tiny yard with walls so high all you could see was a square of sky far above. Once, a bird had fallen from the sky and she and the other women with her gathered around it. Mikki had picked it up. For the first time in years, she had touched another living being, feeling it’s small heart fluttering in her hands.

It was a surreal moment, listening to her describe all those murderers gathering around the bird, praying to God that it wouldn’t die. And then, suddenly, it ruffled its feathers, and they watched as it flew high over the walls and disappeared into freedom. “God answered our prayers,” Mikki said.

That was the best story I heard. Otherwise, Mikki talked about other friends who wrote to her or visited her, the television shows she watched. She was very bitter about her sentence. She was innocent, she said. She refused to talk about the crime.

She did remind me a few times that she was a nurse, a kind person who cared about other people. When she had first been put in jail, awaiting her trial, she’d saved another woman’s life who’d been choking on an apple. This was true, it had been mentioned in the press.

“Is that the action of a murderer?” she demanded of me, her eyes, always wide as if confronting some confounding surprise, growing wider, her voice taking on a slightly belligerent tone.

I could only shake my head, no, of course not.

When I mentioned the letters, I expected a light to shine in her eyes, a far-off expression of nostalgia to overtake her. But nothing of the sort happened. She had forgotten about them. They hadn’t held any magic for her. It didn’t occur to her how brilliant and unique the letters were. Her TV shows were far more interesting.

I remembered how Casey had once said that most murderers are boring people. Mikki was boring. She had no imagination. I asked if she still had the letters and she said, yes, she would have to take them out and look at them again. But I got the feeling that perhaps she had thrown them away, that she probably wouldn’t even bother looking for them in her room.

The original letters. It was hard for me to bear. I had poured over those letters, read them so many times. The copies I had were precious to me. She didn’t seem to understand how much effort it had taken Casey to write the letters, or what an unusual thing it was for a person to do.

I visited her one more time, asking if she could bring the letters with her so I could see them. But she didn’t. Our second conversation was much the same as the first. Nothing of interest or value was said, just talk of TV shows and how unfair life was and such banal comments they aren’t worth repeating here.

I began to doubt Casey’s belief in her innocence. Could he have been wrong? I ended up meeting with her lawyer Verna Wefald and reading through the 1,000 pages of the habeas trial. I saw how the original trial and Mikki’s conviction had certainly been unfair.

The prosecutor Katherine Mader had formerly defended Angelo Buono, one of the Hillside Stranglers. In that case, she had fawned over Buono and treated him like a misguided little boy, a tactic used to humanize him for the jury. With Mikki, she had done the opposite, likening her to ‘a Nazi working in the crematorium by day and listening to Mozart by night,’ a ‘mutation of a human being,’ a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing,’ a person who ‘stalked people like animals,’ and someone who had “resigned from the human race.”

Casey had explained all this to me and that a trial like that can make or break a District Attorney’s career. Mader won the case. And she became a Superior Court Judge.

Casey had known what I came later to understand very well myself, that whoever tells the best story, or perhaps even more important, whoever tells the story with the most money and press behind it, is the one who wins.

Perhaps Casey had wanted desperately for this one story that he had told of Mikki to be true. And in that, he was no different from anyone else. We all create the stories of our lives, and we tell them over and over and we want them to be true.

Was Mikki innocent, or had she told herself that story so often over the years that now even she believed it?

During our second visit, Mikki got angry with me, she didn’t want me to tell her story. She said she only agreed to see me because she understood I wouldn’t write about her. But that wasn’t true. Between the first and second visit, she had sent me a children’s book idea she had, some of it written, wanting me to get it published, but it was terrible, to be honest, and there was nothing I could do about it.

I argued with her, but Mikki, don’t you want to truth to be told? So many people have said such horrible things about you, don’t you want to tell your side of the story, after all, you have nothing to lose. But she was insistent.

After the second visit she cut me off and I never went back. In fact, even without her cutting me off I doubt I would have returned. It seemed after the initial spark of interest on both sides, we had nothing more to say to one another.

It takes a certain type of person to be able to absorb such stories, to sit with such monsters and listen. But it is a necessary undertaking. Like Dr. Berko, I understand just a little bit the strength it takes to interview these people, to put your own feelings aside and let them speak.

The monsters Dr. Berko got to know, and the monsters Casey got to know are different in some ways, but in other ways they are the same. All monsters have sad stories to tell of the past. But monsters are still monsters all the same, and given half a chance, they will kill you too.

To this day, doubts remain in my mind about Mikki. Is she innocent or not?

However, of one thing, I am sure. I would never want to share a house with her.

You can find out more about Casey in this Los Angeles Times articles He Tries to Prove There’s a Little Good in Everyone

You can find out more about me and Silvia Sanchez in this Los Angeles Times article Sparks in the Darkness

That's so interesting! Small world.

Karen,

What an amazing life you've led!

The interview between Jonathan Sacerdoti and Dr Anat Berko was incredible and enlightening.

I follow Tzlil's substack and both mother and daughter are beautiful human beings.

Stand for Israel 🇮🇱

Shalom.