The Power of Words

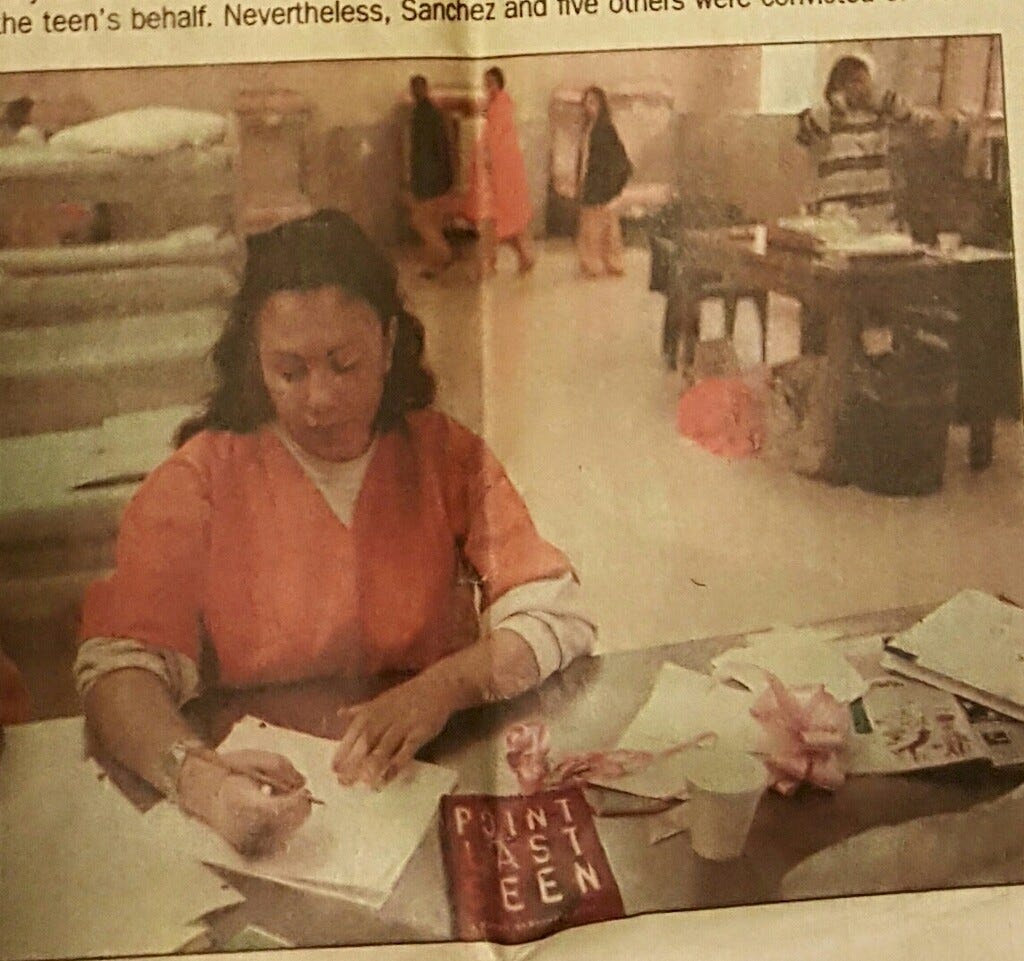

"I have exchanged my weapon for a pen; my battlefield for a blank page." ~ Rocky, Central Juvenile Hall, Los Angeles, 1996

Once a month, I do my best to publish an inspirational essay. Most of my writing deals with such very dark subjects I felt it was important to make a balance with some uplifting and encouraging words. Not just for my readers, but for myself, because it isn’t always easy writing about such terrible things. Some of these inspirational essays have been hidden behind a paywall. Slowly but surely, I am bringing them to life for everyone to read. I love all of these essays. They are more personal and mean a lot to me. I hope you will enjoy them. This essay was written in 2022, and it is as relevant today, perhaps more so, than it was then.

I know that some of my readers are offended by swear words and I respect that. Please be advised that there are some of those in this essay. If I avoided everyone who used such words, I would never have met all the wonderful girls that I write about in this essay—or a lot of other people. This is the reality of life.

I hope my readers and listeners will consider becoming paid subscribers. It is thanks to you that I am able to spend the long hours needed to research and write and record my essays.

One-time or recurring donations can also be made at Ko-Fi.

You can listen to me read this essay here:

Anyone with one iota of common sense knows that dividing children based on race, telling one group that they are the oppressed and the other group the oppressor, focusing on differences rather than commonalities, creates division, fear, and hatred. These are tactics used by gangs. This is what prison does. This is how tyrannical governments control the populace. These are the techniques of dictators used to pit one group against another to weaken them so that they do not rebel against their oppressors.

Do those in our school systems know this? Of course, they do. We can only conclude that they are propagandists, not educators, intent on imposing their psychological perversions upon those who are under their influence.

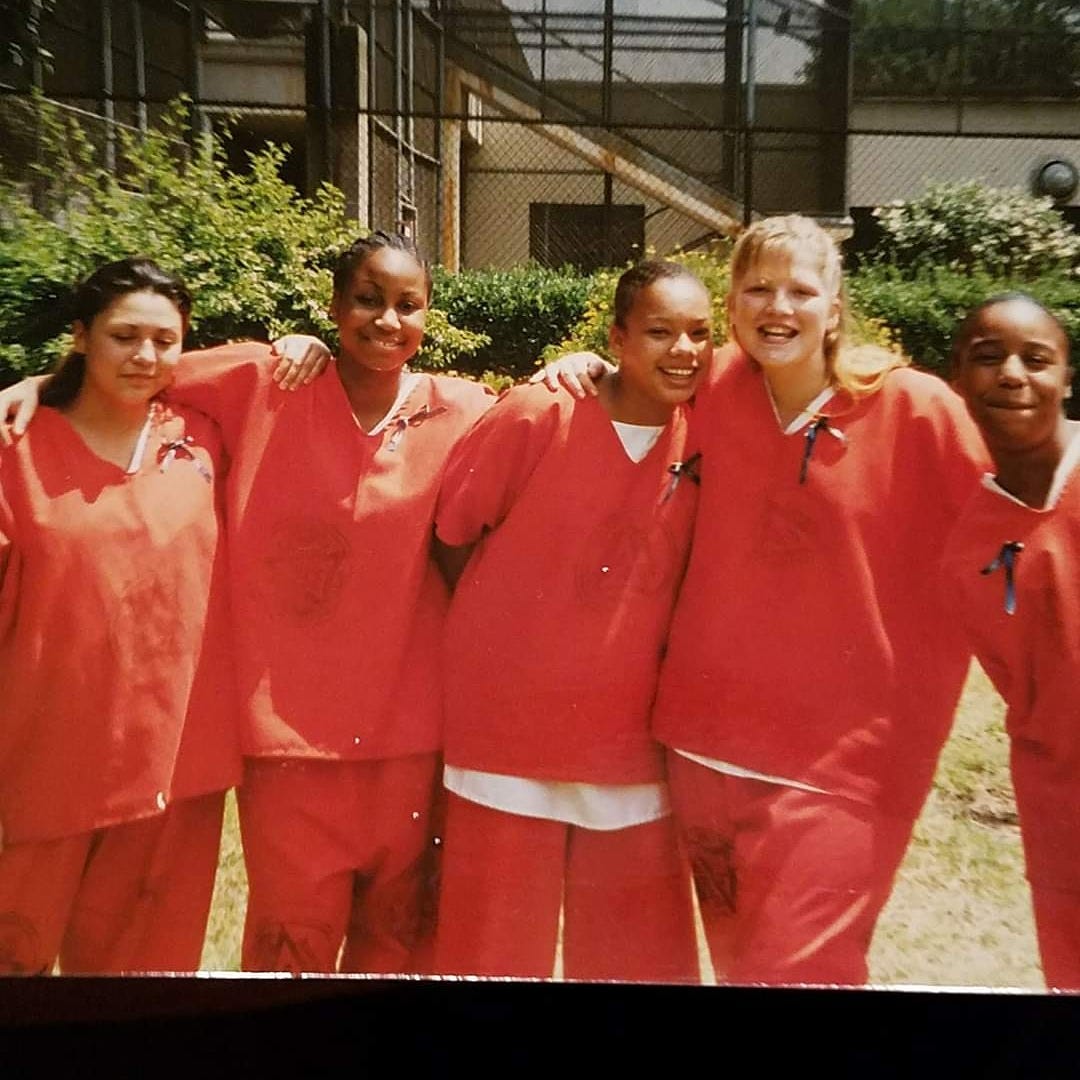

Back in 1996, I started a creative writing program for incarcerated youth in Central Juvenile Hall, Los Angeles. Imagine if I had gone in there and said, hey, I’ve got a great idea. I’m going to have these kids write about their lives but I’m going to separate them by their gangs and by the color of their skin. I’m going to encourage them to think about all the ways they hate one another and I’m never going to suggest that it could end. Instead, I am going to reinforce those differences by constantly reminding them of how unfair it all is. Oh, and the white kids will be ostracized by the black and brown kids and will be berated and shamed into confessing that they are the privileged oppressors of everyone else.

In those days, the teachers and the staff would have looked at me like I was crazy. I would be reinforcing everything that the gangs they belonged to had already told them they needed to do in order to be protected from enemies on the other side of the street. My teaching methods would have only made it a hundred times worse.

I started teaching my first group of girls sometime in the early winter of 1996. I’d gone in months before that to teach a few classes in the girls’ school. I had been blown away by the power of their writing and after careful consideration, I had decided to go back. I had a vision to start a creative writing program that would give a voice to youth, boys and girls, who had never been given a voice before. Society considered them monsters. Maybe they were and maybe they weren’t but why were they here and what had happened to them? Why not listen to what they had to say?

The unit where they were housed was called Omega. Hmm, sort of biblical, I thought, reminded of the Bible verse, about Jesus being the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.

Fittingly, Omega was on the furthest end of the vast compound. In order to reach it I had to pass through a number of gates, buzzed through by guards lazily sitting in their guard houses, and listening to music. Finally, I made it to the last checkpoint and nervously knocked on the door. It was a Saturday and their free time. How would they react? Would they make fun of me, pull disrespectful faces, tell me to f**k off, or worse, refuse to even participate? Perhaps I would have to leave admitting defeat.

Entering Omega, I found myself face to face with forty sullen girls staring at me from their bunk beds without much interest.

Ms. Pincham, senior staff in charge, greeted me. Known simply as Pincham, she was a big-boned Black woman dressed in casual stretch pants and an over-sized t-shirt. On a belt around her waist hung a hefty can of mace.

Pincham didn’t waste time on pleasantries. “I’ve picked some girls for you, the ones that’ll be here the longest so they can get the most out of it. They’re all High-Risk Offenders. HROs. They’re the ones dressed in orange, here for the most serious crimes.”

She gave me a penetrating stare to see if I was grasping what she was saying. I nodded.

“I’ll call the girls,” she said. “But watch yourself.”

As one of the other staff ladies called out their last names, the inmates rose off their beds, bright orange blobs that turned into girls with names and faces. As they lined up, Pincham gave me the rundown on each of them.

Hill and Lorenzo were both accused of armed robbery. Hill, a tall black girl, looked too beautiful, sweet and serene to have done such a thing. Highly religious, she continually expressed her innocence. A case of mistaken identity, she said.

Osuna and her homeboy had stolen a car, ran over a police officer, and were chased all the way to the Mexican border. She was shot in the back by border patrol officials and dragged from the car. I suppose nowadays, it would have been all over the news as further proof of racism within the police force. Back then, the news covered it without bias, just as what had happened. When her grandmother came to visit Osuna in the hospital she was so happy—until she discovered her grandma’s only reason for being there was to get her hands on the $700 robbery money Osuna had hidden in her panties.

Jacobs was a blond, blue-eyed accomplice to a murder. Jacobs alone knew what had really happened that night since the man charged with committing the crime was discovered a few months later, shot dead in the desert. When the authorities brought Jacobs in, she was examined and found to be pregnant. Shortly before I met her, she had given birth to a little boy named Aaron. Jacobs refused to say who had fathered the child but Pincham was sure it was the murderer. As with all babies born to incarcerated females, Aaron was taken away from his mother within twenty-four hours of his birth. Luckier than most, or at least I hoped so, custody was granted to Jacob’s father, not to the State.

At the age of fourteen, Rocha was the youngest of the group. She was accused of murdering her social worker on a dare.

“Oh yes,” Pincham said. “She’d done it.”

This wasn’t hard to believe since Rocha was one of those rare kids who didn’t deny her crime. Rather, she’d look you right in the eyes and admit it without showing one bit of emotion.

Lorenzo was a feisty sixteen-year-old in for robbery and assault with a deadly weapon. At the age of ten she’d walked across the Mexican border carrying nothing but a backpack with a stolen Barbie doll inside. A border guard had taken pity on her and sent her to live with her aunt in San Diego. Unfortunately, as is often the case, life this side of the border hadn’t proved much better for Lorenzo. On a violent night in the park, she’d been caught with a gun while her homeboys abandoned her and ran.

Andrews was a short, shy black girl in for kidnapping and rape. She was accused of abducting a girl off the sidewalk, holding a gun to her head and driving around town with her older, male cousin, trying to sell the girl for $20. When no one seemed interested, Andrews had jumped out of the car in disgust, telling her cousin to kill the bitch for all she cared. The cousin didn’t take her up on the suggestion, but figured, why not, since nobody else had raped her, he might as well do it himself. Afterwards, he had dumped the victim by the side of the road.

Sanchez and Gonzales were in for robbery and murder. They kept to themselves, the toughest and meanest of the bunch. No one messed with them, after all, they were 187s, and commanded respect. They had a reputation to live up to and an obligation to play the part.

Pincham had a little extra to say about them. “You better watch those two. They’re quiet, don’t hardly speak at all except to each other. But there’s a lot going on underneath. Talk about stress. And I can’t say I blame them. They’re facing life without parole.”

“So, did they actually do it?” I couldn’t resist asking.

Pincham shook her head and rolled her eyes as if I was an idiot. “Of course not! Sanchez’s boyfriend did it. I don’t know the whole story, though.”

“So, what about Rocha, what’s she facing?” I asked.

“Fifteen years to life,” said Pincham.

“That doesn’t make sense,” I said. “You say she committed the murder and she’s facing less than the two girls who didn’t?”

Pincham let out a dry laugh. “You solve the mystery of this justice system and then you come back and explain it to us, okay?”

The girls were now lined up at the back of the room waiting quietly with their hands behind their backs. To the left of Pincham were six long steel tables and she motioned for them to sit at the one closest to her desk. Great, I thought. She’ll be listening to every word.

She turned her aggressive stare on the girls. “Now sit,” she ordered. “And behave yourselves.”

Finally, it was time.

All of the girls sat down except for one. She wore glasses and was tall, with thick, strong arms and legs and a round belly that pulled on her county shirt. Like most of the other girls, her complexion was sallow from lack of exercise, fresh air and healthy food. I wasn’t straight on the names yet but I thought she might be Osuna.

“Hey, friend, I remember you,” she said in a booming voice that echoed throughout the room. “You wanna chair?”

Before I could answer, she brought me one and placed it at the head of the table.

“Now, you sit here, it’s best,” she commanded, positioning herself directly to my right, my watchdog from the very beginning. From that day onwards, no one would dare usurp her spot.

I hadn’t even started, and I was already feeling desperate. Not fifteen feet away, Baywatch was on TV, two scantily clad lifeguards were locked in a passionate embrace, the sound so loud it was impossible to ignore the smacking of lips, the sighs of delight, and the heavy breathing. Two staff members were yelling reprimands and Pincham was on the telephone. Half of the girls at my table were transfixed by Baywatch, the other half talking amongst themselves.

“Hey, quiet!” yelled the big girl to my right, banging her fist on the table. “Show some respect.”

Heads snapped around in surprise and the talking stopped. I gave her a grateful look. She might be loud and overbearing, but for some reason, she had decided to look out for me.

“Okay, thank you. My name’s Karen (at least back then my name wasn’t a bad word). How are you all doing today?”

Oh, that was a lame question. How good could they be doing, stuck someplace where none of them wanted to be?

Most of the girls looked back at me and said, “Fine,” unenthusiastically. The two girls at the end of the table ignored me completely, lost in their private conversation.

“Could you please introduce yourselves? I’ve been told your names, but I need a reminder.”

The big girl started. “I’m Osuna.”

“If you could give me your first names, I’d appreciate it.”

“That’s cool. Elizabeth Osuna. You gonna start coming every Saturday?”

“I think so.”

“Great, cuz I like to write.”

The girl next to Elizabeth whacked her arm. “Shut up. It’s my turn.”

Elizabeth stuck out her chin belligerently. “Who you talkin’ to, bitch?”

“Ladies!” yelled Pincham.

My state of panic increased. Name-calling already and I hadn’t even been with them five minutes. How long would it take before the fistfight started?

I expected the girl next to Elizabeth to get madder but instead she smiled nicely—a little too nicely—while twirling her long, gorgeous locks between her fingers. “My name’s Maria Lozano. And I know how to write, unlike some people.”

She stared off into space with a look of supreme superiority. Fortunately, Elizabeth did nothing but emit a loud grunt.

The blond girl said, “I’m Janice Jacobs. Don’t pay no attention to them. They always get into it.”

“Uh, huh, oh, and you don’t?” Elizabeth jibed.

Janice stuck out her tongue.

I waited for the last girl on the right side of the table to speak. She was still talking to her friend across from her, oblivious to the rest of us.

“Hey!” said Elizabeth. “Your turn, come on, girl.”

Slowly, disdainfully, she turned her head, as if just noticing us for the first time. Her eyes were big and expressive and right now they wanted everyone to know she was bored. Tattoos marred her light olive skin.

“Who, me?” she asked in a voice so soft; I could barely hear her. “What am I supposed to do?”

“Your name,” said Elizabeth impatiently. “If you got one.”

“Oh, okay. Sanchez, Silvia. What we doing here anyway?”

“Oh, come on!” said Maria, exasperated.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I’ll explain in a minute.” I nodded at the girl across from Silvia. “And you?”

“Leonore. Leonore Gonzales,” she answered. Her voice was even softer than Silvia’s and at odds with the defiance on her face. The tattoos on her face were the mirror image of her friend’s.

The next girl had light brown hair and freckles on her nose. “I’m Erika Rocha.” It was the girl who had killed her social worker. She looked as innocent as a baby.

“Oooh,” said Elizabeth in a cutesy voice. “My lil’ sis.”

“Brittany Andrews,” said the short black girl, her eyes downcast, offering nothing more.

“Ipress Hill,” said the tall one. Almost apologetically, she continued, “I’m a poet. I’ve done a lotta writing, I even won a poetry contest at school. But I don’t know why I’m in this group. I’m going home soon.”

“Hill shouldn’t be here, she’s innocent,” Maria explained. She started chanting “innocent” and all the girls except Silvia and Leonore chimed in.

“Shut up!” ordered Elizabeth, suddenly remembering her self-appointed responsibilities. “You know Karen ain’t gonna come back if you do that.”

“Oh, sorry,” said Maria, giving me another of her radiant smiles. She folded her hands on the table and put on a demure face, just like a model student.

“Okay, okay,” I said. I picked my bag up off the floor and plopped it on the table. Everyone looked at it curiously. Even the two renegades at the end of the table couldn’t help stealing a glance.

“We’re going to start doing some writing. I guess you all know that’s what this is—a writing group.”

They nodded.

“So, first, we need pencils.”

Elizabeth jumped up. “I’ll get them.”

She came back with a tub filled with stubby pencils with blunt ends.

“Can we sharpen them?” I asked.

Elizabeth threw up her hands in mock horror. “Damn, are you serious? We might stab each other.”

“Seriously, just like that?” I asked.

I had a hard time imagining them taking their pencils and stabbing each other right then and there.

Maria twirled her pencil wickedly. “Oh, no, we wouldn’t do it now. We’d wait ‘til later, hide ‘em down here.” She pointed down her shirt.

It was amazing, I was to discover, what they could squirrel away in their bras.

Ipress laughed. “Yeah, but how about that Montez girl, huh? Remember what she did?”

“Hell, yes. That bitch was scandalous,” said Maria. She looked at me, suddenly self-conscious. “Oh, excuse my language.”

“Okay,” I repeated. Much as I was curious about the Montez incident, we needed to get back on track. “I’m going to pass out some notebooks. They’re different colors, so please, everyone try to choose what you like and hopefully you’ll all be happy.”

I pulled out the notebooks and the minute I put them down, the girls dove in.

“Blue, that’s my color!”

“Red, gimme red!”

“No, I want red!”

“So take it heina, here’s another one.”

“Black, that’s mine!”

“Ladies!!!”

The table went silent. Pincham towered over us, grim with disapproval. She snatched the notebooks.

“Can I talk to you, Karen? At my desk.”

“Watch out,” mouthed Elizabeth.

I followed after Pincham, wondering what was wrong. Slamming the notebooks down on her desk, she spoke loudly and distinctly so that everyone in the room perked up to listen.

“You should know better than to bring in gang-related materials.”

“Excuse me?” I said, completely baffled.

She held up two of the notebooks. “Blue? Red? You ever hear of Crips and Bloods? Not to mention a few others?”

A murmur of excitement went around the room. Just saying the names gave everyone a shot of adrenaline. Pincham frowned. “Shut it! We can’t have this in here. It’s against regulations, and for a very good reason. These colors can kill. You’ll have to take them home.”

Giggles flitted across the room. What a disaster. It was one of those things I should have known if I’d had an ounce of experience. I felt sure that if Pincham could, she’d have slapped me in orange and sent me to my bunk in disgrace. Still, I had to salvage the situation as best I could.

After apologizing for my mistake, I said, “How about this—I’ll tear off the covers. Then they can still write in them.”

I demonstrated with one. It didn’t look nice, but it worked.

Pincham wasn’t pleased, but she was fair enough to concede. “Okay, I guess you can do that. But try and think next time, okay?”

I ignored the jab. We took the notebooks back to the table and each girl tore off a cover, Pincham keeping a close watch to make sure every offending bit of color was removed.

“There,” I said. Defaced notebooks now lay in front of each of them.

With great surprise, I saw that the atmosphere around the table had completely changed. Everyone wore smiles and was looking at me with attentive interest. Even Silvia and Leonore wore tiny grins. Instead of causing the girls to lose respect for me, being chewed out by Pincham meant that we were now connected. Pincham didn’t like me. They didn’t like Pincham. I was cool.

I plunged right in, taking advantage of the unexpected camaraderie. “I’d like you to write a piece titled ‘Me.’ Think of it as if you were painting a self-portrait, as a way of getting to know yourselves better. But be careful, it’s like lifting a lid of Pandora’s Box. All sorts of things begin to fly out. Oh, of course, maybe you don’t know about Pandora?”

They shook their heads, so I told them the story.

“Oh, yeah,” said Ipress. “I remember that story from school. It’s a myth.”

“You tell good stories. You gonna do it some more?” asked Maria.

“Sure,” I said, pleased with the compliment.

“But what we gonna do right now?” asked Brittany. “I wanna write but I don’t get what you mean.”

I tried to explain. “Writing is just like talking. It’s like having a conversation with someone, only you write it down instead of saying it. All of you can talk, all girls can. It’s a girl thing. We love to gossip and blab to our friends.” I looked pointedly at Silvia and Leonore. They just stared back, expressionless once again. “Writing is no different. Feel free to write anything you want about yourselves. Anything you feel tells who you are. Whatever comes to mind. Except your crimes,” I added hastily. “You have court cases and you can't write about that.”

Their faces remained as empty as the papers in front of them. No one even picked up a pencil.

I tried again. “Okay, it’s like this. When you meet a person for the first time, what’s the first thing you notice?”

Maria smiled. “If it’s a guy, his eyes. That’s so important.”

“No, no,” said Elizabeth. “His shoes.”

“Girl, what?” said Ipress.

“It’s true. I mean, if it’s a guy, I always look at his shoes first. You can tell if he got cash, if he got taste, by the kinda shoes he wears.”

“Hey, heina,” said Janice. “Money don’t mean nothing when you’re trying to find a good man.”

“Hold on a minute,” I said. “So, now we’re talking about men? How’d we jump there? This is supposed to be about each of you.”

Elizabeth let out a loud guffaw. “It don’t matter where we start, we always end up there.”

Just a few minutes ago the talk had been about stabbing each other with pencils and now they sounded like typical boy-crazy teenagers. They flipped back and forth from one extreme to another and it was hard to keep up.

“You’ve all made a good point,” I said. “The first thing we notice about people is their physical appearance, and that means their shoes, hair, color of their skin, the clothes they’re wearing. If we consider them beautiful or ugly, smiling or frowning. We judge people by the way they look, even if we say we don’t, we do. We can’t help it. We judge ourselves that way, too. We look in the mirror and what do we see?”

Elizabeth grimaced. “Don’t even make me go there. Now, Rocha, she’s pretty. She don’t mind looking in the mirror.”

Erika smiled. Yes, she was pretty, but with a disconcerting emptiness in her eyes. So far, she hadn’t entered into the conversation at all.

I continued. “That’s where we start, with the physical, but it’s only the top layer.”

“You mean you want us to describe the blood and guts underneath?” said Brittany, horrified.

“Oh, come on, girl, you know she don’t mean that,” said Ipress.

I laughed. “No, I don’t. Beneath the surface there are layers and layers to each one of us. It takes courage to peel back the layers because it means exposing yourself to others—and yourself. What makes you laugh and cry? What makes you get angry? What’s your worst and best childhood memories? How do you think other people see you as opposed to how you see yourself? Ask yourself these questions and see what answers you come up with. In fact, let’s write those questions down on our papers and then answer them one after the other to get going.”

They seemed to get the idea then and everyone started to write. Relieved, I sat back, happy to take a break for a minute. I rubbed my eyes and when I looked up, Silvia was staring at me. Quickly, she turned back to her paper. I was surprised to have caught her with a thoughtful, intent expression on her face, something she obviously didn’t mean for me to see. It undermined her previous demeanor, which had very clearly stated, “I don’t give a shit.”

I moved my chair down to the other side of the table, explaining I wanted to divide my time equally between both ends of the group. Elizabeth gave me a disapproving frown but didn’t try to stop me.

I smiled at Silvia. “How are you doing?”

She shrugged, not looking at me, working away with her pencil.

I saw that nothing graced her paper except her last name, written over and over in different styles of gang script. I saw that Leonore’s paper was empty.

“Can I be excused?” said Leonore. “I don’t feel so good.”

“Sure,” I said. “Come back when you feel better.”

Silvia watched her friend walk away. “She won’t get better and she won’t be back,” she said. Silvia had a way of speaking softly but with a hard edge. “She don’t wanna be in the group. Is it mandatory?”

She didn’t lift her head when she spoke, just her eyes, challenging me from under thinly plucked brows.

I knew Pincham wanted it to be mandatory but I didn’t see the point of forcing them to come past the first class.

“No,” I told her.

She nodded.

We stared at each other, dark brown eyes meeting light gray.

I thought she’d get up and walk away, too, but she didn’t. Instead, she asked, “What you doing here, you got kids?”

“Yes, I have three.”

Her eyebrows shot up. “Damn, how old are you?”

“Thirty-nine.”

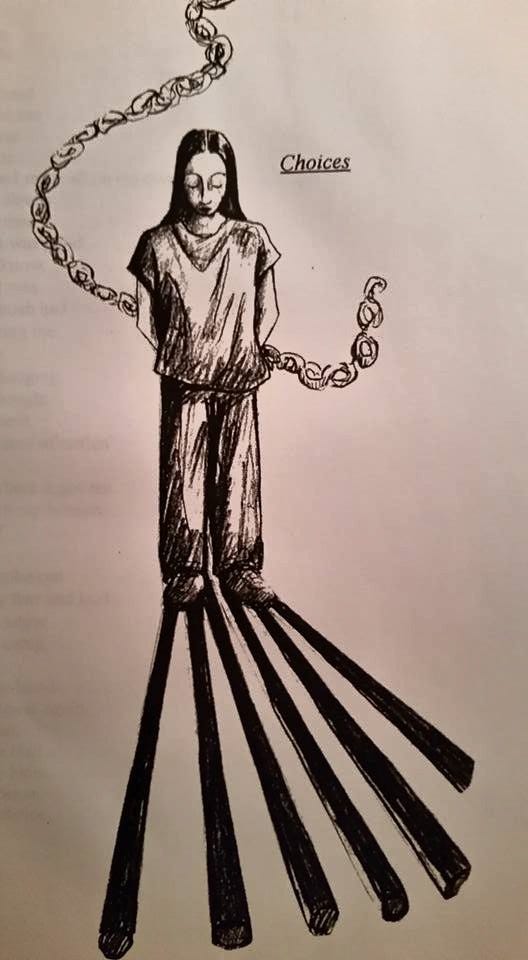

She jabbed her paper with her pencil. “Yeah, well, when I’m as old as you I could still be in prison. And somehow, I don’t think I’ll be looking so good.”

“How long have you been here?” I asked.

“A long time. You know, my hair was blond when I got here, now it’s all grown out black. My hair’s like a calendar, I kept track of the time by how much it grew out, but now I been here so long, I can’t do it no more.”

“That right there, what you just said, is as good as any writing,” I told her approvingly.

“But I can’t write like I can talk.”

“You will, I promise,” I told her.

I looked around the table, glad to see that everyone else was writing. When they were finished, Maria eagerly said she wanted to read. I was amazed to see how respectfully the other girls waited to listen to her. She cleared her throat dramatically a few times, then began to read:

Sometimes I sit here and think about my lonely, sad vida. As I go back to my miserable childhood it’s like a dream going back and having flashbacks. Now my nights are filled with sad desperation, remembering all I went through. Now I sit and think and I really hate the fact that I was ever born. You know why? Cuz I was never really born. My life, it has been a dead life, always in darkness, never in peace. My heart is like a time bomb, ready to explode, ready to give up on life.

It all started in the year of 1983 on a cold afternoon. I was only four years old. That day my mother and father had been drinking with some relatives, Uncle Mondo and Aunt Ester. It was the first time I remember looking at the world and I was surprised because I was so tiny, so gentle, so little.

So at age four I was raped. That afternoon my eyes were opened and my mind was destroyed. My whole childhood was thrown away like a piece of trash.

From that day on my nightmare began. Day by day, when the night would come, I would wonder if he would forget. But it was too hard for him to forget. He knew my room was open. I would always hide under the sheets but it was too late, he was already there, waiting. He wanted to see my little face crying and suffering. He liked it. I hated it.

All these years I put up with all those nights, all those terrible moments of pain. I cried. I was just four years old. I couldn’t understand why the world was like that. I didn’t know who I was.

Maria stopped. While reading, she had changed from the self-assured gang girl to a broken child. There she stayed, rocking back and forth and nursing her pain. The girls on either side reached out and put their arms around her.

We all sat huddled together at that cold steel table, awash in strong emotions aroused by Maria’s words. The television still blared, the staff still yelled, but now it was just a muffled background noise that barely registered.

In that moment, I became afraid of what I was doing. Why had I come here? What right did I think I had to open up such wounds in these girls when I had no idea of how to heal them? I thought to myself, You can still get out, walk away and not come back. There’s still time. But once I came to a few more sessions, once the girls got used to me, began to depend on me being there, it wouldn’t be so easy to escape. I couldn’t make promises I wasn’t going to keep. Not when so many people had let them down.

Even scarier, what would happen if I began to depend on them? I had wounds, too. Ones I wanted to bury and try to forget. This writing brought them back again.

I had no answer for Maria or for any of them. All I could do was sit silently in my chair, completely lost.

After a moment, Maria raised her head and said, “I wanna write a story about my life. You think I could do that?”

I nodded. “Absolutely. You have an excellent voice. I was very impressed with your writing ability.”

My words seemed inadequate to me, but she smiled, almost her old self again. “Good. I wanna write it all down because I think about it a lot.”

Relief overcame me. They would find their own way.

One after the other, the girls read their writing. All of them told tales of abuse and neglect. I was amazed at their honesty. I hadn’t expected it so soon, if ever.

When it came to Silvia’s turn, she refused to read.

“Shall I?” I asked.

She shrugged.

I took the paper and she didn’t try to stop me. I read the words.

My life is like a game I always wanna win so to win I cheated but instead I lost.

On that first day, I discovered how profound each one of them was, all in their own ways.

At the end of class, I gathered up the papers, assuring them when they asked that I was coming back.

As I left, Pincham gave me a curt nod. “You did good,” she said, and ridiculously I almost felt as proud to hear her compliment as the girls had been to hear mine. I continued to teach those classes for about six years. Out of it grew a nonprofit called InsideOUT Writers. I am no longer involved. Ironically, I was canceled by the elite board of directors of the organization I had started with the purpose of giving a voice to those whose voices were taken away.

And then, cancel culture came out of the closet and into the mainstream as the accepted way of silencing anyone who dissented with the leftist agenda.

I would never be able to teach these classes today. Just the fact that I am a white woman would preclude me from doing it—especially with the unfortunate name of Karen. I can’t tell you how many times I have been lambasted for my name. How did I ever dare to go into juvenile hall and try to “save” those girls of color? Anything I do is tainted with my colonial, white privilege arrogance.

It was the same when I dared to teach girls in Luxor boxing. White liberal women in the United States condemned me. Only an Egyptian woman should do it.

I will have more to say about the boxing club when I publish my personal story of Luxor, but for now, here is my student Aya who used to climb over the garden wall if I didn’t answer her knock soon enough, training to the music of Sade.

Of course, there weren’t any Egyptian women in Luxor that could teach boxing. So, that meant no one should? How did I learn martial arts in the beginning? Someone came to America from the countries where it had been practiced for hundreds of years and taught it to me and others who were interested in learning. Should they have not come? How does anyone learn anything if we can’t learn from others who are different than we are?

I didn’t have some agenda when I went there. I set up a boxing bag on my terrace and kids started arriving. One day I came home to find about 25 kids outside the gate pleading to be able to box. Should I have said, oh, no, sorry, I’m white, I can’t teach you!

The absurdity is beyond belief.

In the same way, how about if I was living in a Los Angeles neighborhood and an Egyptian family moved in next door and I saw the father practicing his stick-fighting/dancing techniques and I was curious and I wanted to learn. Would my white neighbors revile him for teaching me something that was not a part of our American culture, of trying to corrupt me? Would they accuse him of trying to be a brown savior?

Below is an example of the stick fighting/dancing and the horse dancing at a wedding. I attended a lot of weddings in Luxor!

Disney did another remake of The Little Mermaid and now Pinocchio. They think that by putting a black actor into a traditionally white role they are being inclusive; that they are practicing equity. But these are meaningless terms used by people who are probably the most racist of all.

I can only imagine how confused Hans Christen Andersen would be by this portrayal of the fairy in his story. Last time I checked Andersen was a Dane writing about his culture. There must be plenty of amazing African legends they can make into movies. Why don't they do that? Why are they "misappropriating" Western fairy tales. Isn't it insulting to Blacks that they force them into roles in "white" stories? Yet, it would cause a huge uproar if a white person acted in an African legend.

At the writing table I saw the power of words. I saw how sharing stories brought people together. Such realizations are dangerous to the regime. It dispels their power to rule through fear and hatred. It unites people together rather than tearing thm apart.

So, this is exactly what we must do because it is the best way to fight back.

I know this is true because I taught the most hardened youth anyone will ever encounter, and I saw the power of words break down the walls of prejudice and hatred. I saw how face-to-face communication brought young people together who would otherwise have been trying to kill each other on the street.

More than 25 years later, some of those girls, like Silvia, were finally released from prison. Others were not so fortunate. When it came time for Erika Rocha to be set free after twenty years of incarceration, she was so terrified of the outside world that she committed suicide.

Through all the prison years and the challenges Silvia faced, through all the challenges I faced on the outside, we remained friends, growing and learning and overcoming.

There is nothing more threatening to the elite than the common people getting together and talking face to face, sharing stories, arguing, laughing. Communicating. Writing words down in the old-fashioned way, on a piece of paper, or in a journal. This is a lost art. When I was a girl, everyone was doing it. You had your diary, and it had a little lock. It was a secret place, just for you. Through writing, you learned about yourself, putting together the puzzle of your life, word by word.

All these ways we had of learning about ourselves and others that relied on our own intuition and interactions are disappearing. We are not supposed to know ourselves. Google knows us. AI knows us. Our psychiatrist knows us. Our government knows us. The algorithms know us.

J. K. Rowling said, “Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic. Capable of both inflicting injury and remedying it.”

She should know. She has been canceled for daring to speak up against mutilating children. She has been canceled for daring to say that you can’t change the meanings of words and not expect dire consequences.

I suppose writing Break Free with Karen Hunt is the culmination of all those years of believing that words mattered, of fighting for the voices of our disenfranchised youth to be heard. Of speaking out when I was told to be quiet.

Nothing is more dangerous to tyranny than this.

One more reason why I can't stand Elon Musk's X. When I shared this essay, they put a warning on it that it might contain "sensitive" content. I refuse the "blue check" and am censored there but this is beyond belief. https://twitter.com/karenalainehunt/status/1749068315585294622?t=TRwuy87Ps0ABbMB9lycRDA&s=19

Karen, This is beautiful. Oh so beautiful on so many levels. I taught school for 40 years. What you have given to others is a wonderful gift . God gave you these special gifts in order for you to give them away. You have touched souls. There is no life better than that. Thank you...