The Power of Words

“Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic. Capable of both inflicting injury and remedying it.” --J. K. Rowling

A new inspirational essay for the month of September.

Anyone with one iota of common sense knows that dividing children based on race, telling one group that they are the oppressed and the other group the oppressor, focusing on differences rather than commonalities, creates division, fear, and hatred. These are tactics used by gangs. This is what prison does. This is how tyrannical governments control the populace. These are the techniques of dictators used to pit one group against another to weaken them so that they do not rebel against their oppressors.

Do those in our school systems know this? Of course, they do. We can only conclude that they are monsters, intent upon imposing their psychological perversions upon those who are under their influence.

Back in 1996, I started a creative writing program for incarcerated youth in Central Juvenile Hall, Los Angeles. Imagine if I had gone in there and said, hey, I’ve got a great idea. I’m going to have these kids write about their lives but I’m going to separate them by their gangs and by the color of their skin. I’m going to encourage them to think about all the ways they hate one another and I’m never going to suggest that it could end. Instead, I am going to reenforce those differences by constantly reminding them of how unfair it all is. Oh, and the white kids will be ostracized by the black and brown kids and will be berated and shamed into confessing that they are the privileged oppressors of everyone else.

In those days, the teachers and the staff would have looked at me like I was crazy. I would be reenforcing everything that the streets had already told these kids they needed to do in order to be “safe.” My teaching methods would have only made everything worse.

I started teaching my first group of girls sometime in the early winter of 1996. The unit where they were housed was called Omega. Hmm, sort of biblical, I thought, reminding of the Bible verse, about Jesus being Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.

Omega was on the furthest end of the vast compound. In order to reach it I had to pass through a number of gates, buzzed through by guards lazily sitting in their guard houses, and listening to music. Finally, I made it to the last checkpoint and nervously knocked on the door. It was a Saturday and their free time. How would they react? Would they make fun of me, pull disrespectful faces, tell me to fuck off, or worse, refuse to even participate? Perhaps I would have to leave admitting defeat.

Entering Omega, I found myself face to face with forty sullen girls staring at me from their bunk beds without much interest.

Mrs. Pincham, senior staff in charge, greeted me. Known simply as Pincham, she was a big-boned Black woman dressed in casual stretch pants and an over-sized t-shirt. On a belt around her waist hung a hefty can of mace.

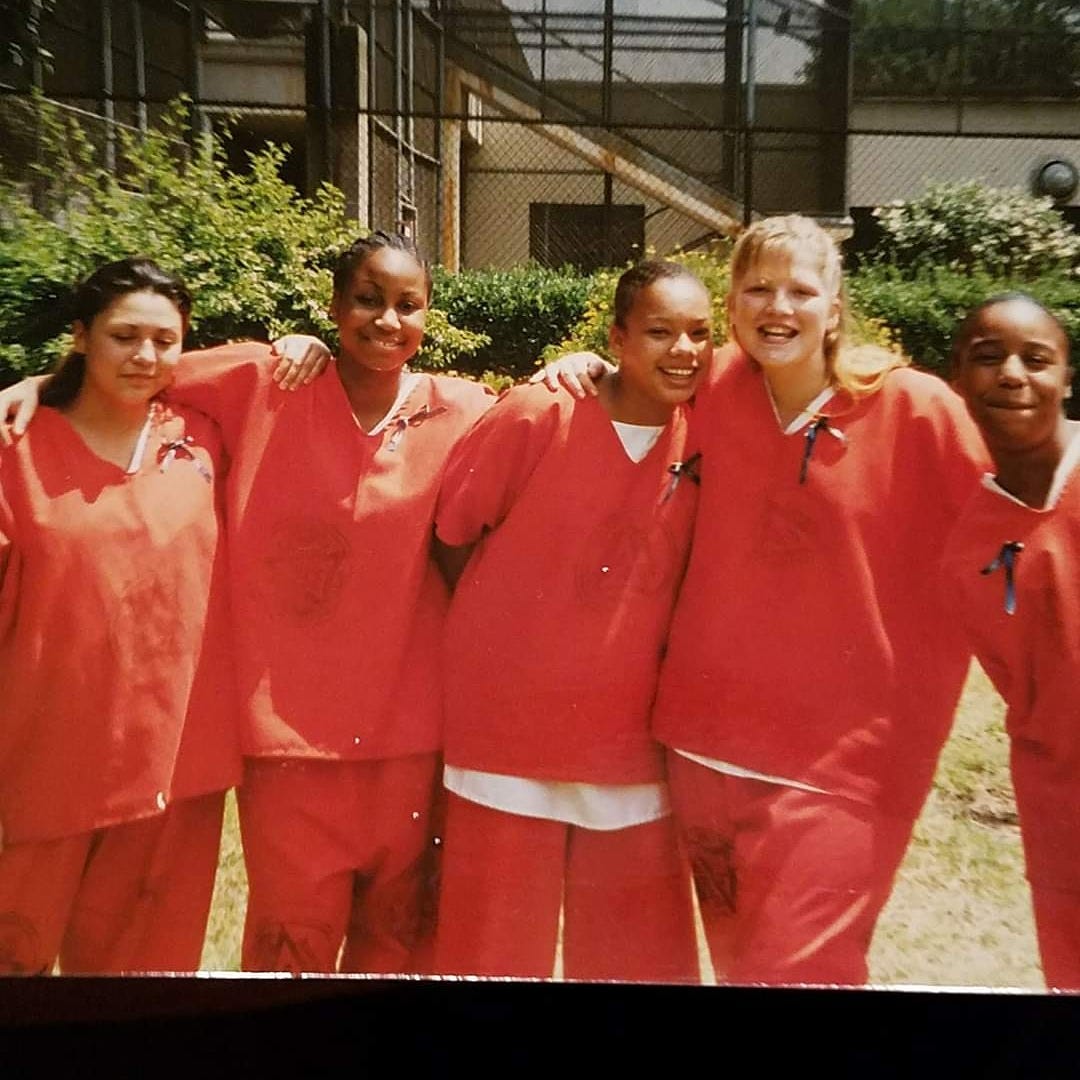

Pincham didn’t waste time on pleasantries. “I’ve picked some girls for you, the ones that’ll be here the longest so they can get the most out of it. They’re all High Risk Offenders. HROs. They’re the ones dressed in orange, here for the most serious crimes.”

She gave me a penetrating stare to see if I was grasping what she was saying. I nodded.

“I’ll call the girls,” she said. “But watch yourself.”

As one of the other staff ladies called out their last names, the inmates rose off their beds, bright orange blobs that turned into girls with names and faces. As they lined up, Pincham gave me the rundown on each of them.

Hill and Lorenzo were both accused of armed robbery. Hill, a tall black girl, looked too beautiful, sweet and serene to have done such a thing. Highly religious, she continually expressed her innocence. A case of mistaken identity, she said.

Osuna and her homeboy had stolen a car, ran over a police officer, and were chased all the way to the Mexican border. She was shot in the back by border patrol officials and dragged from the car. I suppose nowadays, it would have been all over the news as further proof of racism within the police force. Back then, the news covered it without bias, just as what had happened. When her grandmother came to visit Osuna in the hospital she was so happy—until she discovered her only reason for being there was to get her hands on the $700 robbery money Osuna had hidden in her panties.

Jacobs was a blond, blue-eyed accomplice to a murder. Jacobs alone knew what had really happened that night since the man charged with committing the crime was discovered a few months later, shot dead in the desert. When the authorities brought Jacobs in, she was examined and found to be pregnant. Shortly before I met her, she had given birth to a little boy named Aaron. Jacobs refused to say who had fathered the child but Pincham was sure it was the murderer. As with all babies born to incarcerated females, Aaron was taken away from his mother within twenty-four hours of his birth. Luckier than most, or at least I hoped so, custody was granted to Jacob’s father, not to the State.

At the age of fourteen, Rocha was the youngest of the group. She was accused of murdering her social worker on a dare.

“Oh yes,” Pincham said. “She’d done it.”

This wasn’t hard to believe since Rocha was one of those rare kids who didn’t deny her crime. Rather, she’d look you right in the eyes and admit it without showing one bit of emotion.

Lorenzo was a feisty sixteen-year-old in for robbery and assault with a deadly weapon. At the age of ten she’d walked across the Mexican border carrying nothing but a backpack with a stolen Barbie doll inside. A border guard had taken pity on her and sent her to live with her aunt in San Diego. Unfortunately, as is often the case, life this side of the border hadn’t proved much better for Lorenzo. On a violent night in the park, she’d been caught with a gun while her homeboys abandoned her and ran.

Andrews was a short, shy black girl in for kidnapping and rape. She was accused of abducting a girl off the sidewalk, holding a gun to her head and driving around town with her older, male cousin, trying to sell the girl for $20. When no one seemed interested, Andrews had jumped out of the car in disgust, telling her cousin to kill the bitch for all she cared. The cousin didn’t take her up on the suggestion, but figured, why not, since nobody else had raped her, he might as well do it himself. Afterwards, he had dumped the victim by the side of the road.

Sanchez and Gonzales were in for robbery and murder. They kept to themselves, the toughest and meanest of the bunch. No one messed with them, after all, they were 187s, and commanded respect. They had a reputation to live up to and an obligation to play the part.

Pincham had a little extra to say about them. “You better watch those two. They’re quiet, don’t hardly speak at all except to each other. But there’s a lot going on underneath. Talk about stress. And I can’t say I blame them. They’re facing life without parole.”

“So, did they actually do it?” I couldn’t resist asking.

Pincham shook her head and rolled her eyes as if I was an idiot. “Of course not! Sanchez’s boyfriend did it. I don’t know the whole story, though.”

“So, what about Lopez, what’s she facing?” I asked.

“Fifteen years to life,” said Pincham.

“That doesn’t make sense,” I said. “You say she committed the murder and she’s facing less than the two girls who didn’t?”

Pincham let out a dry laugh. “You solve the mystery of this justice system and then you come back and explain it to us, okay?”

The girls were now lined up at the back of the room waiting quietly with their hands behind their backs. To the left of Pincham were six long steel tables and she motioned for them to sit at the one closest to her desk. Great, I thought. She’ll be listening to every word.

She turned her aggressive stare on the girls. “Now sit,” she ordered. “And behave yourselves.”

Finally.