Reflections for a Sunday: Life & Death

"How can we grow up, and heaven has this blueness, the earth has this greenery, and the Lord has this fragrance, and the heart has this wondrous power to love, and the soul has this infinite energy."

"How can we grow up, and heaven has this blueness, and the earth has this greenery, and the Lord has this fragrance, and the heart has this wondrous power to love, and the soul has this infinite energy of faith."

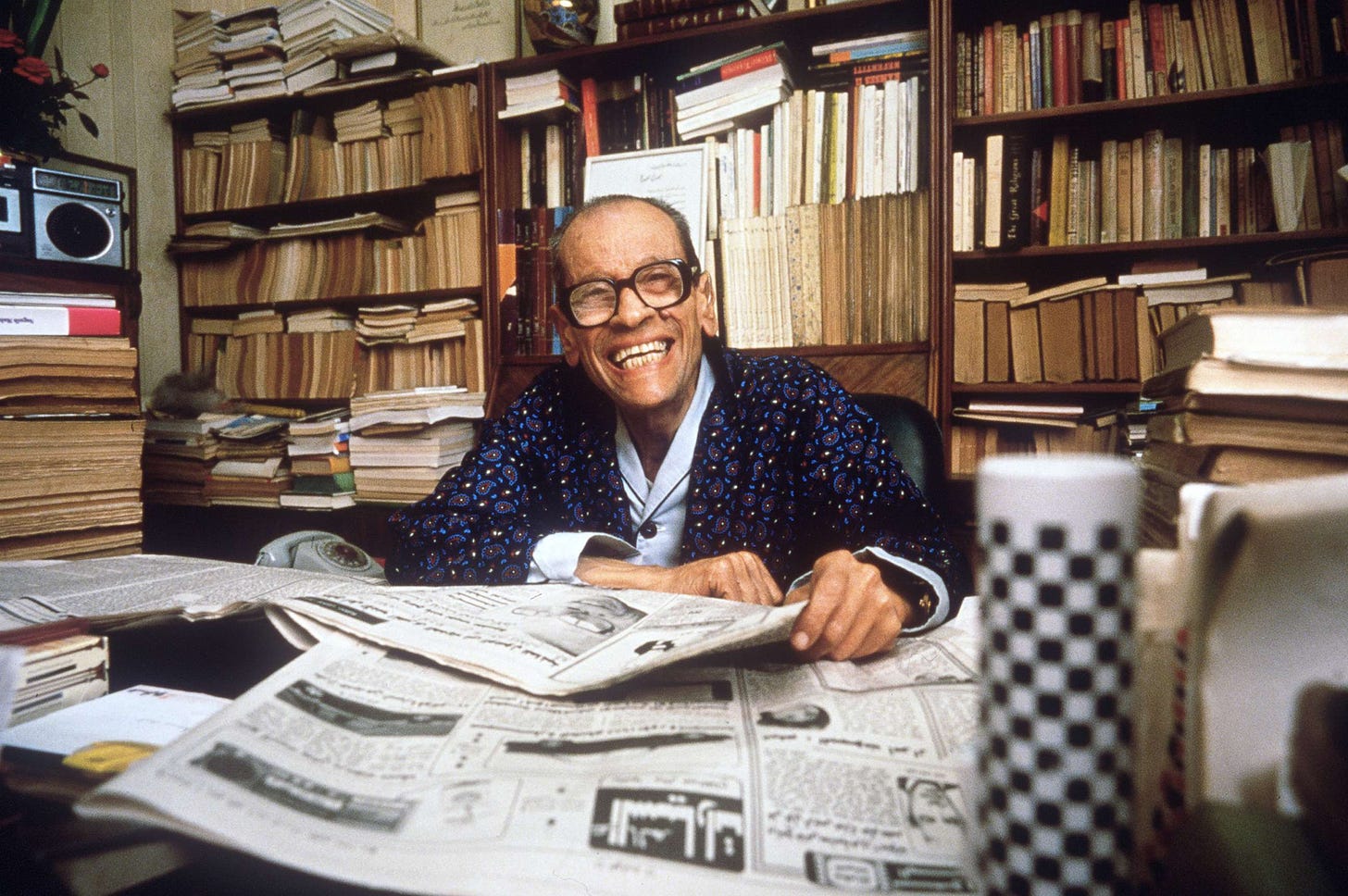

― Naguib Mahfouz

You can listen to me read this essay here:

One-time or recurring donations can be made at Ko-Fi

This coming week, I plan on sharing some short videos that I took while living in Luxor, Egypt. The mysterious, haunting beauty that drew me to this magical place. After that, I will publish at long last the story of my adventures in Luxor and just how deeply I got involved in life there.

One of my favorite authors is Naguib Mahfouz. I discovered his books, the Cairo Trilogy, well, I don’t remember exactly when, but it must have been in the early 1990s, around the same time I discovered the writings of Salman Rushdie.

It was in 1989, that the Iranian Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued an apostasy fatwa against Salman Rushdie, but what many people don’t know is that he wasn’t the only writer to be targeted by Khomeini.

From ABC News are the brave writers who defied the fatwa:

Ettore Capriolo

Ettore Capriolo, an English literature expert who had translated "The Satanic Verses" into Italian, was stabbed multiple times on July 4, 1991, in Milan, Italy. He survived the attack. The attacker was never arrested.

Hitoshi Igarashi

Eight days later, a 44-year-old Japanese scholar, Hitoshi Igarashi, was found stabbed to death at his office.

A year and a half earlier, Igarashi and his publisher held a press conference in Tokyo to announce their translation of Rushdie's work.

Aziz Nesin

Turkish writer and humorist Aziz Nesin started translating "The Satanic Verses" in the early 1990s. In May 1993, Nesin published excerpts from the controversial novel in the newspaper Aydinlik.

The move, along with some of his speeches led to riots in Istanbul by Islamic fundamentalists who denounced Nesin for “spreading atheism.”

A few months later, a mob organized by Islamists gathered around the Madimak Hotel in Sivas, to protest the presence of Nesin. They set the hotel on fire. Nesin and many other guests escaped, but at least 37 people were killed.

William Nygaard

Publisher William Nygaard, who had put out a Norwegian translation of Rushdie's novel, was shot three times outside his home on Oct. 11, 1993. He survived the attack, but was hospitalized for months.

Naguib Mahfouz

Egyptian writer and Nobel Prize laureate for literature Naguib Mahfouz was stabbed in the neck by a Muslim extremist outside his Cairo home on Oct. 15, 1994.

He survived the injuries, but his right hand was paralyzed afterward.

Mahfouz had denounced the fatwa against Rushdie, saying that "the veritable terrorism of which he is a target is unjustifiable, indefensible."

The fatwa was forgotten for years, only to be revived in August 2022, when Rushdie was stabbed fifteen times as he was about to give a talk on how the United States was a safe haven for exiled writers. Miraculously, Rushdie survived the attack.

It’s quite incredible, how brave these writers were, and still are, as recently as a couple of years ago, speaking out defiantly in the face of death. It was so obvious, what was right and what was wrong. Rushdie’s latest attack should have reminded people how the hatred of the West and our freedoms never ends and how it can reach us even here.

But that didn’t happen. How quickly the tide changed. On the eve of the one-year anniversary of the Oct 7th massacre, no one would have denied a year ago that Khomeini was evil. Yet now, incredibly, millions in the West cry out in support of his successor, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. The two men are no different: their love of death over life. It is the West that has changed. Somehow, we now welcome those who call for our death, as if we are committing some sort of mass suicide.

In a rare sermon on Friday, Khamenei praised Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel as a “logical, just and internationally legal action”. He referred to Israel as “a rabid dog,” “blood thirsty,” and “wolf like,” and said that “any strike on the Zionist regime is a service to humanity.” He wore a Palestinian checkered kaffiyeh, a clear message to all the Western protestors who proudly wear the scarf without realizing its bloody history and how it represents their own deaths, not life or freedom for Palestine, as they suppose.

As I left for Luxor around Christmas time of 2017, there was no war, and the fatwas seemed a distant memory. Life has always been filled with such contrasts, anyway, and I was not one to deny myself the possibility of learning something new, just because of potential danger.

"When calamities multiply, they wipe each other out.

and crazy happiness comes to you with strange taste

And you can laugh from a heart that no longer knows fear!" ~ Naguib Mahfouz

And so, I got on a plane from Phoenix, Arizona and made the long journey, landing first in Istanbul, then Cairo, and at last taking a small plane to Luxor.

No story of Egypt can start without the Nile. This great river captured my imagination from the first moment I laid eyes on it. I had seen it as a child, but that had been from the ground. I had never seen it from the air. The entire flight, it lay beneath me, winding on and on forever, like a great snake.

Flying from Cairo to Luxor all you see is desert, endless desert, cut in half, right beneath you, by the Nile. There is no river in the world that so expresses life in the midst of death as the Nile. All along the riverbanks are trees and lush foliage and fields of grain, date palms, mango and banana trees. And then as if God had taken a knife and cut a line on either side to say that beyond this line life must not pass, the green turns to yellow.

This is Egypt. The life of the Nile and the death of the desert.

In Luxor, when the sandstorms come, it’s as if the gods have risen up in anger, seeking to envelop every living thing and bury it with the bones of the pharaohs. But the sand can never defeat the water, it can never fill the Nile, no matter how it rages, and the storms are always vanquished, until they rise again.

From the moment I landed in Luxor, I loved that contrast, that battle between two forces unable to defeat one another, living side by side, always in a dance of flood and drought, the people dependent on the whims of the water and the land. That battle was nothing like it once had been before the Aswan Dam was built. In 1970, Nassar’s dream was fulfilled of taming the Nile and the Aswan High Dam was finished. Unfortunately, for Nassar, he was assassinated before he could experience the result of his labor. The dam brought to an end the annual cycle of flood and drought in the region and exploited a tremendous source of renewable energy.

Oftentimes as I sailed the Nile, bending over the edge of the felucca and looking into the waters, I sensed the river’s anger and resentment against being tamed, hidden within its dark depths. The Nile is a heavy river, holding many secrets. I was told no machine of man can ever reach its bottom, it is so filled with sludge that once something sinks down there, it never comes up again, nor can it ever be found.

With the sandstorms, I sensed the same anger and resentment, long buried with the bones of the pharaohs and rising up when called by the gods. The sand and the water are filled with discontent that they can no longer battle one another as they once did in ancient times.

Getting off that plane, I didn’t know how angry Luxor was, the land, the water, the people, and the spirits. If you do not believe in such things, go live in Luxor, and you will see. But don’t go there unless you are very strong within your own spirit.

Instead, I felt excitement and anticipation. I had dreamed of coming back so many times. And now, here I was. Perhaps, I could set my wandering to rest. Perhaps here, in this place where I had experienced such magic as a child, I would find my home at last.

In part, I can thank the writings of Naguib Mahfouz, in particular, The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, Sugar Street, for my hope, since I revisited his writings shortly before I decided to go to Luxor.

Mahfouz said, "One's homeland is not the place of one's birth, but the place where all attempts to escape end."

I had spent much of my life escaping bad situations, not least of all, Egypt itself days before the 6 Day War. This should have been the end of my escapes, but it turned out to be my most dangerous escape of all. Even so, I miss Luxor in the depths of my soul.

During the pandemic, all the tourists fled. Riding my bike along empty village streets and then the long avenue leading to the Valley of the Kings, past the Colossi of Memnon, it felt as if I had traveled back to my long-gone childhood days. How well I remembered our family pulling a mattress out on the balcony of the Winter Palace to escape the heat and falling asleep to the sound of wild dogs howling across the Nile. Now, if it was close to sunset, the wild dogs came out of hiding and I had to sometimes beat them away with sticks as I raced by on my bike, my heart thumping in my chest. Perhaps they were really ifrits, guarding the tombs, who knows. It’s easy to have such thoughts among the tombs of the Pharaohs.

Ifrits are a type of powerful and cunning jinn, winged creatures of smoke and fire, who haunt ruins and torment and kill those who dare to disrespect them.

Only a handful of the tombs are open to the public. It is said there are many more still to be discovered. Walking on the sand of the west bank, I had a sense of wonder, knowing that beneath my feet lay treasures still to be discovered along with the rotted bodies of the dead who had hoped to take it all with them into the afterlife.

It is not unusual for villagers to find artifacts beneath the earth of their properties. These villagers are the descendants of the tomb raiders of old and they seldom reveal what they find to the authorities, knowing if they do so, they will be forced to give up their homes and likely be compensated a pittance for their findings. And so, they keep their secrets, just as they have always done, funneling their findings into the still thriving black-market treasure business.

It seems the earthly gods never learn their lesson. They use and abuse the common folk, but as with the villagers of Luxor, it is usually the common folk who have the last laugh. The Pharaohs intermarried, thinking it kept them pure and strong when it only weakened them. They expended all their energy on building monuments and stuffing their tombs with riches, mummifying themselves so they could live forever. None of this worked. Meanwhile, the people who had been enlisted to build the tombs and decorate them, defied the gods, refused to believe in the fearmongering stories of ifrits and robbed the tombs, growing richer than the Pharaohs and living longer in the process.

The Pharaohs are long-gone. But the villagers remain.

During the years I lived in Luxor, I heard many stories of magic and lost treasures. The villagers are fabulous storytellers. They will assure you that they believe their stories. They learned their magic from the best, the Pharaohs. It is in their blood to surround you so completely with smoke and mirrors that all sense of reality disappears, and you are lost under a spell.

Many evenings I found myself at The Rest Cafe, just opposite the forbidding El Qurn Mount, Stella beer in hand, listening to spell-cast stories. One such story, I will never forget, told to me on a starry night when the moon hung full, and the dogs howled beneath it.

The current owner of The Rest Cafe is a descendent of Sheikh Hussein Abd el Rassuhl, a member of the Howard Carter expedition that excavated the tomb of Tutankhamun. He was a mere child at the time and acted as their water boy. It was this boy who all villagers agree led Carter to the right place to dig for the tomb.

As far back as the 13th century the inhabitants of Abd el Gourna had not only secretly mined for treasures from the tombs and sold them, but had built an entire village into the mountain, inhabiting even the tombs themselves. These people lived and breathed the mysteries of The City of the Dead. They became a dynasty of tomb raiders.

The greatest of them all were the Abd el Rasul brothers, Ahmed and Mohammed.

These brothers had an instinct, perhaps placed in them by the gods themselves, to discover the secrets hidden within the mountain. At night they would search for the tomb entrances by lamplight. The ancient Egyptians called this “Hy,” or “He who knows the secrets of the location of the tombs.” It is said they drank of a potion left inside the tombs for the pharaohs to give them long lives and insights. This is why the curses that befell others never befell them.

In 1871 the brothers’ lives changed forever. One of their goats fell down a hole in the sand and disappeared. Cursing the loss of a goat, they climbed down after it and discovered Deir Al-Bahri, a vast tomb where priests from the 20th dynasty had buried 40 mummies along with thousands of papyri and other treasures hoping to hide them from ancient thieves. The Abd el Rasul family told no one of their find and began discreetly selling off the treasures. But as more and more treasures appeared on the market in Cairo, word got out and speculation arose. The government sent the first Egyptian archeologist, Ahmed Pasha Kamal, to investigate. The police caught the brothers and tortured them. But no amount of torture could make the brothers reveal the location of the tombs. After some months, Mohammed was released. But of Ahmed, nothing was ever heard of since.

When Mohammed was released, he made a deal with the government. In exchange for an enormous sum, he gave up the location of Deir Al-Bahri to Kamal. In fact, the brothers had argued about this before, Ahmed vowing never to give away the family secrets, while Mohammed had come to realize that their tomb raiding days were over, and it was time to reinvent themselves.

In return for this fabulous information, Mohammed became very wealthy, and that wealth was passed down through the generations. The Rest Cafe and the land upon which it is built is owned by Mohammed’s descendants. The cafe is not a tourist destination, in fact it seems the owners care nothing for tourists, which is unusual in Luxor. It’s whispered that beneath the cafe are untold treasures to be excavated but the family refuses to give up this land. Even more interesting, is that the government has not forced them to do so.

But what happened to Ahmed? It was said both brothers loved the same woman, another reason for them to hate each other. Did one brother betray the other? Have Ahmed’s remains joined the millions of other bones still hidden within The City of the Dead?

Perhaps we will never know. Perhaps this story isn’t even true. These are the mysteries that tantalize us and keep us guessing. These are the mysteries that fuel our imaginations and bring excitement to our lives.

It’s sad to think that nobody wants mysteries anymore. We’ve become obsessed with truth while at the same time insisting that truth doesn’t exist. It you don’t agree with something someone else says, it has become “misinformation”. I hate that word. I refuse to use it except as I have used it here—to rebel against it.

I remember when I first started teaching creative writing in Central Juvenile Hall, in Los Angeles, people thought I was a fool. This was in 1996, before it became “cool” to go into prisons like that. I was working with High-Risk Offenders, youth facing life sentences for serious crimes. The youngest in my class was fourteen-year-old Erika Roche, who had cold-bloodedly shot her case worker on a dare. She ended up spending around 25 years in prison. When it finally came time for her to be released, she killed herself rather than face freedom. She didn’t know how to survive beyond those walls.

We really don’t appreciate what we have, do we. People told me back then; those kids are monsters. They’re liars. They’d as soon kill you as talk to you. They’ll just write lies; you can’t trust them. What’s the point?

My answer was, why would I care what they write? It’s called creative writing; they can say anything they want. And if they tell me a story that I believe, I will praise them for writing so well. In fact, since they were free to say what they wanted, telling lies was never an issue. They were free to say anything.

Often what they said was such searing truth, that I would go home and weep from those stories of pain and suffering and how they then turned around and caused the same pain and suffering to others.

Freedom is a scary thing. It’s messy. It can be downright dangerous. But it’s worth it.

I think about all the stories I heard from those girls in juvenile hall, like Silvia, when she finally found the courage to start writing, wondering how she could have trusted the man who abused her and committed the murder for which she was standing trial:

That night, why can’t I forget that night? I wasn’t supposed to be there. Me and Claudia, we were supposed to go see some other guys but then Jerry showed up and I was afraid to leave. Oh, if only I’d left before he got there!

I’m trying to let go. I dunno what to say to him or myself. I loved him once, maybe I still do. I’m so confused. He was my teacher and I was the student and I was a good student so I learned.

Like the very first lesson. He taught me how to make love, something I didn’t know. He’s the only person I ever made love to, real love. He gave me an “A.” I wasn’t a virgin when I came to him but he made me feel like one. So I enjoyed my lessons. I’m letting go but how can I let go of that memory?

But then things started to change and I no longer enjoyed my lessons. He changed. He wasn’t no longer the teacher I met. People started telling me, Silvia, you’re fifteen and he’s in his twenties, you’re too young for those lessons and he’s too old to give them to you. Silvia, he’s not teaching you love, he’s raping you. Can’t you see it? Silvia, why are you crying? Does love hurt that much? Silvia, why can’t you no longer go out with your friends and family? Is that part of the lessons he’s teaching you? Why can’t you no longer have fun? Why can’t you eat, Silvia? Why can’t you stop crying, you’re making a river of tears.

I was crying cuz my teacher left me for another student. I never failed his class but he left me. So now, I’m trying to let go, day by day.

How could anyone say that writing wasn’t true. It’s universal. I saw the same stories played out before my eyes in Luxor, from the women who so craved love that they would do anything the men told them to, they endured the abuse, the humiliation, just to be loved. And then, when they realized it wasn’t love, but hate, they told themselves more stories, so they could keep on living.

Luxor is a land of lies but at the heart is so much truth.

This is how life is. It is not disinformation. It is the stories people tell themselves to go on living. If we see it like this, there is nothing to fear. This is what I found out behind the prison walls of juvenile hall with those girls I came to love. And it all came back to me in Luxor in ways I never could have imagined. Anyone can put themselves in a prison, anywhere, but not everyone can free themselves. Often times, freedom is more frightening with the truth it makes us face, than the prisons we make for ourselves.

It’s the brave storytellers that remind us of what freedoms means.

Those who hated Salmon Rushdie, like extremist cleric Abdel-Rahman, known as "the blind sheikh," blamed it all on Naguib Mahfouz. He said that if only Mahfouz had been killed, his book Children of Our Alley would never have been written and, therefore, Rushdie would never have been inspired to write The Satanic Verses.

How could such stories be so dangerous. They weren’t even true. But fiction can be truer and more dangerous than what is fed to us as “true”. We are not allowed fiction anymore. It’s “disinformation”.

I am a lover of stories, and nowhere did I hear more enchanting, more horrific, more beautiful stories than I did in Luxor. But in the end, I had to escape that place, too.

I end with a quote from Palace of Desire, my favorite of the Cairo Trilogy.

"The truth is not harsh, but escape from ignorance is as painful as childbirth."

Beautiful poetry

Karen, you are an angel.

It is a sunny lovely day. I listened to your writing today as I am sewing patchwork pumpkins.

Thankyou for sharing your knowledge and interest in Luxor, and your experiences.

I have learned so much. I worked for 10 years for an orthopaedic surgeon in Alexandria Virginia, before marriage and kids. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/washingtonpost/name/rida-azer-obituary?id=2269493 He was such a generous and lovely man. I was too young and busy to ask questions about him, and his life and how he came to the US but his Obit tells a lot. He would fly home via the Concorde several times a year.

God Bless you dear friend