Reflections for a Sunday: Castles, Zorro and Aliens in a Strange Land

In that village school, I learned that people can seem different--and it isn’t always about color, it can be about class, education, culture, religion—but underneath, we are all basically the same.

You can listen to me read this essay here:

For this beautiful Sunday, I thought I would tell a bit more of my childhood adventures traveling and living abroad, to give some relief from all the heavy topics lately. I have many new subscribers (thank you!) so please bear with me, those of you who already know, as I explain how it happened that my family had all these adventures.

In 1966, when I was ten years old, my dad heard the voice of God telling him to give up his successful business career and become a writer. As a result, we left our home in Los Angeles and began traveling the world so my dad could gain inspiration for his books. We had no set plan, we landed in London and proceeded from there. I’ve written about some of our adventures, such as smuggling Bibles into Romania and escaping out of Egypt right before the 6 Day War.

One-time or recurring donations can be made at Ko-Fi

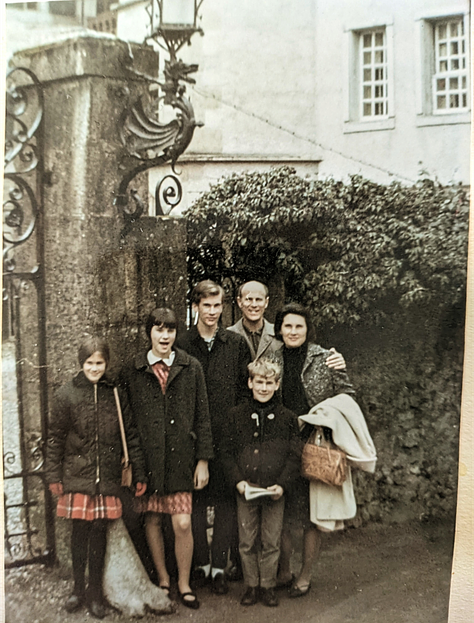

This story touches on my experiences living in a 17th century castle in the village of Echandens, Switzerland and most specifically, attending the village school. Living in a castle with turrets and dungeons and a winding central staircase was a dream come true for a girl with my vivid imagination.

My older sister, Janna, was just as imaginative as me, and the stories we made up as we explored the castle, and its grounds were better than anything we could have ever imagined back home in boring Woodland Hills. I have many more stories to share about that!

Everything would have been perfect if only our parents hadn’t decided it would be a good experience for us to attend the village school. All four of us had to go, my older brother Davy, Janna, me, and my younger brother Jon. None of us wanted to.

On the first fateful morning, we were roused from our beds before dawn, a cruelty that we found inexcusable, the air so cold our breath was cloudy. Outside, it looked as if it was the middle of the night. It was never dark like that when I got up for school in Los Angeles. Never freezing cold, the kind of cold that had no mercy.

“I'm not going!” I sat at the kitchen table, tears in my eyes.

“Me neither,” said Jon.

Janna and Davy sat in stoic silence.

“Eat your breakfast.” Mom sounded severe. Her lips were pursed. When she did that, there was no moving her.

“It'll be good for you,” said Dad, doling out blobs of oatmeal into our bowls.

I stared down at what looked to me like throw-up. I wasn't going to eat it.

Mom put milk on the table, in a pitcher. We got the milk from the local farmer, warm from the cows. Mom would leave the milk to sit until the cream rose to the surface. Then, she would skim off the cream and whip it with a hand whisk, expressing delight when it actually started to thicken and turn to cream. Dad made Dutch apple pies and loved to pile a mountain of whipped cream on top.

At first, I was suspicious of that milk and cream. It smelled and tasted funny to me. I preferred the kind that came out of a carton, like the milk back home. But after a while, I got used to it.

“The teachers are looking forward to having you there,” said Mom. “The other students will be so curious; you'll probably be treated like movie stars. Lots of attention.”

Great. The last thing any of us wanted was lots of attention. It would not be of the movie star variety, of that, I was sure. I wanted to go back to my room, pull the quilt up to my chin and keep reading Wind in the Willows. I wanted to join Ratty and Toad and all the others on their adventures and leave mine alone. Anyway, we weren't obligated to go to school, the schools back home had given us the year off. All we needed to do was keep up with our math. How could our parents do this to us?

But what choice did I have? My parents always said, “This family isn’t a democracy.”

As we walked out of the gate, leaving our cloistered world behind, the sun was rising above the village, shifting the black to a pale gray. The ground beneath our feet crunched with frost. I didn't know it was possible to be so cold, to suffer so much.

And I have to do this every day, I thought.

Even Saturdays, because there was school on Saturday mornings. We had Wednesday and Saturday afternoons off and all-day Sunday. But, of course, on Sunday we went to church. So that meant we never had a single day—not a single one, where we could sleep in. We left for school in the dark of the freezing early morning, and we came home in the dark of the freezing late afternoon. Incomprehensibly, the Swiss took time off from work and school at noon and everyone went home for a leisurely hot meal, then returned. It made the day interminably long. And, we had to walk back and forth to that hated schoolhouse four times a day. What a wasted effort!

Winding through the village that first morning, vigilance was necessary in order to dodge the cars speeding through the narrow-cobbled lanes. More than once, we found ourselves jumping back, bodies pressed against a wall to avoid being smashed. On the other end of the village, the imposing schoolhouse loomed on a small rise, within a gravel courtyard; a two-storied, squat building with a set of stairs leading up to the entrance door.

Just as we entered the gate, the tinkle of a bicycle bell sounded behind us, along with a jolly, “Bonjour!”

We drew aside to allow the bike to pass. On it was hunched an old woman who looked exactly like every Disney fairytale of a witch on her broomstick, the edges of her flowered dress billowing beneath a great coat, a scarf wound around her head and neck. On her feet were a pair of big black rubber boots. How she managed to maneuver a bike in those boots without falling off, I didn't know.

We watched in horror as the witch came to a halt in front of the schoolhouse, got off and walked up the steps, her short, sturdy body slightly hunched forward, her big boned, construction worker hands swinging back and forth.

“Is that our teacher?” cried Janna in dismay.

“I can't believe this!” I grumbled.

“I'm not going in,” said Jon.

“Yes, she’s our teacher,” said Davy, who always seemed to know everything. “But not yours, Jon, I think you have a different one. Anyway, her name’s Madame Petriquin.”

“What?” we all said at once.

Davy rolled his eyes. “Come on,” he said, and we all followed him inside.

We shortly found out that there were only two teachers and two classrooms. The students were divided into two groups, younger and older. Jon was stuck in the younger class, separated from the rest of us. His teacher was younger too and didn't look half as scary as ours, but he was still terrified to be on his own. He would have rather faced the old witch if it had meant being together.

From the first miserable day, I hated that school. We all did, although somehow our parents continued to maintain that we loved it. “What a wonderful experience,” they'd exclaim. Except that they weren't the ones experiencing it, so they didn't know.

Gathered with the other kids in the foyer, we were greeted with giggles, grins and friendly hellos. A few of the kids tried to speak to us but we just shook our heads. Eventually, they gave up. The doors to the two classrooms opened and we waved Jon good-bye, his face a pinched mask of fear.

The first thing we found out was that we should have brought slippers. No shoes were allowed inside the classroom. The other kids found it very funny that we didn't know such an obvious rule. This was only the first of many misunderstandings giving rise to jokes and laughter, making us feel more and more isolated with each passing day.

I had never been in a classroom filled with so many busy, noisy and badly behaved children, of such a wide age range. Nobody seemed to be able to sit still and be quiet. Some were throwing things and even fighting with one another.

Madame Petrequin yelled for quiet and amazingly, everyone obeyed, although they all immediately turned to look at us as Madame introduced us to the class. At least, that’s what we assumed since the teacher gestured in our direction and said our names, and everyone greeted us in unison.

Madame was truly ugly; I just don't know any other way to describe her. Her skin was deeply lined, and she had a large a wart on the end of a bulbous nose, yes, a wart, just like a stereotypical witch. She had stringy gray hair that looked like it was never washed, held back in an untidy bun. But the worst thing was her teeth. They were yellow, with brown stuff stuck between them as if she never used a toothbrush. She was a teacher, but she didn’t even know the basics of personal hygiene. It was disgusting. Back home, elderly ladies at least tried to look younger. They dyed their hair, wore make-up and push-up bras. Not in Europe. Old ladies looked old, and they didn't try to hide it.

Once the class had settled down, Madame called us up to her desk where she let out a stream of guttural French, sounding as if she was constantly clearing her throat in order to spit. And actually, she did spit. I had the unfortunate luck of standing in the line of fire. As she spoke, projectiles hit me in the face numerous times, but I was too intimidated to move or try to wipe it away. So, I just stood there enduring it, thinking, this woman is a health hazard, I’m going to get some horrible disease.

We all stared at Madame as she spoke, trying desperately to understand her rapid words, thinking that maybe, miraculously, if we just listened really hard, it would make sense to us.

It didn't.

At last, she handed each of us a cahier, a booklet. She demonstrated what she wanted us to do by drawing a very bad likeness of a cat and then, underneath, writing the French word for cat: chat.

Ah, yes, so we were supposed to draw pictures of things and then write what they were in French. The other children would help us.

That's how we spent most of our time. Drawing pictures in our cahiers and writing the French words underneath: horse, cat, cow, rose, tree, house, and so on. There were a lot of words. This could keep us busy for a very long time. It was mind-numbingly dull. I loved to draw, but not like this.

The classroom never stayed quiet for long. There were two boys who were constantly in confrontations with Madame Petriquin; a battle she seemed to enjoy just as much as they did. They were bigger and older than the other kids. We found out later that they had taken the exit exam more than once and hadn't passed. So, they'd simply stayed in the village school.

“How old do they have to be to get out—a hundred?” Davy wondered disdainfully. He might have looked down on them, but he didn't dare show it in school. Davy's brain was big, but his muscles weren't, and he was no match for these guys.

These boys were a hand full, demanding everyone's full attention with their rakish, devil-may care attitudes. One had freckles and a mass of wiry, dirty blond hair—and when I say dirty, I don't mean it as a term describing the color, I mean it was really dirty—and everyday he wore the same homemade brown sweater that looked three sizes too small. Fashion wasn’t something these kids were big on, they all wore the same outfits day after day, no variation. The other kid was darker, taller and less muscle-bound, and more morose than his gregarious friend. Janna and I immediately nick named the blond one Tom Sawyer and the darker-haired one Huck Finn.

From that very first day, Tom and Huck began trying to attract Janna and my attention by making loud, very obvious “pst” sounds and throwing spit wads. We ignored them as best we could but most of the other kids found it quite amusing and kept looking over, smirking and giggling while Janna and I grew increasingly uncomfortable.

Madame reprimanded the boys a number of times to no avail. Eventually she rose from her chair and marched down the aisle towards them, unleashing a torrent of sharp language and kicking them in the shins. Wow, Janna and I couldn’t help gasping in shock.

When the kicks seemed to have no effect, she positioned herself between the two of them, still lecturing, and began slapping them about the head, first one and then the other. When this produced no results other than bigger smirks, she took a ruler from her large pocket and commenced wrapping them on the knuckles.

I watched in fascination, feeling like I really had entered a chapter of Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer.

“Can you believe this?” Janna whispered to me.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the drama, nor could she. We’d never seen anything like it. If a teacher had behaved like this back home, she’d probably lose her job for child abuse. In fact, the parents would have sued the school long ago and insisted the boys’ graduate. But then, the boys would have no doubt ended up in jail before long.

Surely, all the bashing must have hurt, but the boys just laughed, and took to hiding their hands under their desks, refusing to bring them out again. Madame tried to pull their hands out, but they wouldn't let her. All the while, the boys kept glancing over at Janna and me as if we should be proud of their fearless defiance, while the other kids in the class laughed or ignored the show.

At last, Madame reached out and grabbed first one by the ear and then the other, twisting hard with all her might. That got a reaction; yelps of pain which they quickly repressed, Madame throwing a fiendish grin at us, as if this display was all for our benefit and we should now be proud of her.

With a ferocious yank, she pulled both boys out of their chairs and deposited them in opposite corners of the room.

The surprising thing was that they actually obeyed without any protest. Over the course of the next few months, we realized that this was an oft-repeated ritual, always ending with the boys pulled by their ears into the corners, where they would stay, often until lunchtime, sometimes even until the end of school, turning around every so often to make faces at the classroom, with the usual glances at me and Janna to see how impressed we were.

Needless to say, I was a model student. Keeping my mouth shut was easy since I didn’t speak French. After a few days, Madame gave each of us a book called “Mon premiere livre” and we were then ordered to copy the French words out of the livre and draw pictures of the words in our cahier. This worked better than us simply trying to think up random words on our own. Day after day, that was what we did.

At recess, our relief at getting out of the classroom lasted for only a few moments before terror set in. I should have had a premonition when the teachers locked themselves in their rooms and the kids were let loose without supervision. My first mistake after I walked out of the schoolhouse was to pause at the top of the staircase. Almost immediately I felt a powerful push on my back and down I tumbled to the great merriment of the children around me.

Nursing my wounds, I turned around to see who had done it, but no one owned up. The other kids were milling about, shaking their heads at my stupidity. A couple of them came up and talked to me, as if they were giving me advice, lecturing me even on how avoid such a calamity in the future.

“It's like they think it's my fault,” I fumed to Janna. “Whoever did that to me should get in trouble. But no, that would be too civilized!”

We met up with Jon who was almost hysterical with anger and fear.

“She's insane!” he said of his teacher. “I think Hitler's in her body. She barks orders. She never smiles, only looks at you with hatred, and then, when she sees you're scared, she smiles but not like a real smile, if you know what I mean. The bad kids, she beats them, I mean beats them. With a board!”

“She can't be worse than the witch,” I said. “Have you seen that wart on the end of her nose? And she spit at me. She’s a health hazard!”

“Getting spit at isn't as bad as getting killed!” cried Jon.

“You're not going to get killed.,” said Davy in a maddeningly reasonable voice.

“We should call the American Embassy,” I said. “We have rights!”

“Oh, sure,” said Janna. “Let's tell them how we're getting spit on by our teacher.”

“Yeah, and what happens when I get beat up by mine?” said Jon.

We were standing by ourselves on the playground, shivering with cold and misery. I say playground, however there was nothing about it to inspire play. It was an empty area enclosed by a chain link fence, resembling a prison yard more than a school yard. The other kids were making a terrible noise, screaming, laughing, running around in circles, sliding across the icy spots, jumping over mounds of snow, always with the intent of gaining the advantage in hitting or pushing one another. They kept looking over, as if trying to impress us with their antics. The teachers were still nowhere in sight.

We simply stood with our chins held high, aloof. They must have thought us to be terribly spoiled. We thought them to be terrible heathens. It was as if we faced off on opposite ends of a battlefield, waiting to see what would happen. At least, that was how we saw it. I think now that they had no intentions other than to befriend us, they just went about it in ways that we found baffling.

“Aren't the teachers coming out to supervise?” Janna wanted to know.

“I don't think that would improve the situation,” said Davy. “They would just join in the violence.”

When Janna and I found out that on Wednesday the boys got the afternoons off while the girls had to stay and learn to knit and crochet, I’d had enough.

“It's not fair to have to stay in school!” I fumed to my parents. “And I hate sewing, I hate knitting. Just because I'm a girl, I shouldn't have to do that stuff!”

But they turned a deaf ear. It was good for me.

Madame Petriquin had us knitting little bears. We made each limb separately, stuffed them with cotton, and then sewed it all together. When I looked at my finished bear, I was actually pleased with myself. It wasn’t bad. But I that didn’t make me feel any better about the injustice of having to stay in school when the boys didn’t.

P. E. was conducted once a week and consisted of running around the dismal playground, doing jumping jacks, deep breathing, stretching and banging on our chests and sometimes even pretending to be animals, such as bears ( there seemed to be an obsession with bears), which meant having to roar and stomp our feet, a disaster since the students inevitably ended up by trying to maul one another and had to be pulled apart. It was absurd watching Madame Petriquin demonstrate each activity with jerky, arthritic movements and then having to imitate them while she watched and critiqued.

For Davy, this was the most dreaded part of the week. He didn't engage in frivolous activities. Running, jumping, getting hot and sweaty, trying to overpower another person physically, these were things he looked down on with disdain. Back home, he was the smartest kid in school. He was captain of the chess team. He did not behave like a Neanderthal.

So, usually, on P. E. days Davy didn't join in, and Madame Petrquin allowed him this privilege. But one day, Jon's teacher came out to lead the class instead and she would have none of Davy's excuses. While we all stood dejectedly, blowing smoke through our noses and stomping cold feet, she barked the order to pretend we were “avions.” While she spoke, she stared at Davy pointedly, making it clear she wanted his participation.

We looked at one another in disbelief. “Airplanes?”

Janna, Jon and I shrugged and began to run with the other students, extending our arms like wings, dipping up and down, making noises like an engine. Davy stood aside, refusing to join in. With a triumphant grunt, almost as if she had hoped he would refuse, Jon's teacher marched up to him and yelled two inches from his face, waving her own arms as if she were about to bomb him. Shocked by her aggressive attitude, Davy had no choice but to try to escape her. In a kind of sick desperation, his face white with humiliation, he raised his arms and began running around the playground, the teacher running after him, pushing him, goading him to flap harder, make louder engine noises. The greater his discomfort, the more triumphant was the teacher's pleasure. It was truly horrific seeing my cultured, sensitive big brother, who I had always looked up to and respected, being reduced to such a ridiculous display, just because this horrible woman wanted to prove her superiority.

In that moment, I felt deep hatred for that woman whose name I cannot remember. Jon had been right. His teacher was much worse than ours. Madame Petriquin might be a witch, but this woman truly was Hitler incarnate. The kind of person who took delight in destroying other people's spirits.

Davy didn't recover from the airplane incident. That very day he demanded that my parents take him out of the school. If they refused, it wouldn't matter, since he was never going back. He would rather die than go back to that insane asylum. Our parents relented and told Davy he could attend the French Lyce in Lausanne. When Janna heard that, she insisted on being allowed to attend it with Davy. They told her she could.

Jon and I were too young to attend the Lyce and so we were left to endure the village school on our own. We pleaded and pleaded to be let out. Our parents remained firm. We couldn't use the beatings as an excuse, since in all fairness to our teachers, Jon and I had never been beaten by them. We were exceptionally well behaved, quiet as little mice, which really defeated the purpose of trying to learn French. We were too scared to speak.

Attending school made our time at home more precious. The television in the sitting room caused some excitement in our family, especially when we found out that our two favorite TV shows, Lost In Space (Perdue Dans La Space) and Zorro, were on once a week.

Our excitement quickly turned to bleak disappointment when we found that both were badly dubbed in French.

We had been so excited learning of the American shows. We had sat down the first time, all of us in a ring around the television, turned it on with great expectation, only to watch the mouths of the actors make strange noises, the words not in sync with their lips, looking ridiculous.

“No,” we cried in unison.

The village kids were obsessed with Zorro. When they discovered that we came from Los Angeles, the “land of Zorro,” we immediately grew in their esteem.

“Hollywood?” they said.

“Oui,” we said tentatively. At least it was a word we all understood.

We tried in our broken French to explain we didn’t actually live in Hollywood, but they weren’t listening.

“Hollywood!” they exclaimed again, talking rapidly amongst themselves.

“Zorro!” they said pointing at us, making signs as if they were fighting with a sword.

“Oui,” we hazarded.

That agreement on our parts was a grave mistake. From that moment onwards, the kids were convinced that we came from the “land of Zorro,” and that we must therefore know Zorro personally. It hadn't occurred to us that they would think Zorro actually existed. But they did. And nothing we said could convince them otherwise. It logically followed in their minds that we must be master sword fighters. Sword fighting wasn’t a thing among the kids back home. We didn’t know how to sword fight—not the real thing. It didn't matter, they were convinced we did, and they were determined to fight us to see who was better. When a kid comes at you screaming a war cry, pointing a sharpened stick at your heart, you have no choice but to defend yourself. We learned to fight out of necessity and really, no one was ever hurt too badly.

Tom and Huck were the leaders of the village gang, and they liked nothing better than to lay in wait for us outside the school grounds. We were no match for them at fighting, but we were pretty good at running. Once Davy and Janna left, the confrontations got worse. They became a daily challenge with the two of us chased home by crazed Zorro fanatics.

Sometimes Tom and Huck played hooky from school and instead of waiting for us outside the school grounds, lay in wait on strategic rooftops where they would suddenly jump down, crying “Zorro, Zorro!” We had to be ever vigilant. Sometimes, it got scary, but we always managed to escape one way or another.

More than ever, I missed my friends back home, especially Kelly. And I’d have given anything to exchange Bill, the school bully, for Tom. Bill was meaner and dumber than Tom but a lot easier and more fun to outsmart since I’d been able to talk to him. With Tom there was nothing I could say since we couldn’t understand each other. To these kids, I must have seemed like some like a dunce. They didn’t know I could talk about lots of different subjects and even crack a joke once in a while.

One afternoon, I was sitting outside on a bench, my back up against the building so I could see all around in front of me and no one could sneak up from behind. At this school constant vigilance was necessary. I shivered. It was freezing cold every single day. How I longed for the hot LA sun and a dip in the pool rather than this miserable loneliness.

The school bell was about to ring, and Jon and I prepared for the run home.

“You ready?” I said.

He grimaced. “Yep.”

One, two, three, the bell rang, the gates opened, and we ran. We were so good at it now, that it was virtually impossible to catch us. On this occasion, we were well ahead of Tom and Huck and a couple more of their friends, thinking that the gate to the castle was open. It wasn’t. Tom let out a yelp of triumph. Jon and I ran to where the castle wall sloped down low enough to climb over. We jumped and I felt someone grab hold of my leg. Jon was on top of the wall and kicked the culprit in the head. They let go and I tumbled over. Once on the other side we jumped up and down and made faces at our pursuers.

“Idiots,” yelled Jon.

Their eyes grew wide in disbelief, then narrowed with rage. They banged against the castle wall, letting out a barrage of words, including, “Nous allons te tuer!” We were getting better at understanding French but still had trouble speaking it.

I made a face at them and yelled, “Quel âge avez-vous les gars? Bet you’ll never graduate, bunch of Bozos!”

We knew we were safe inside the castle grounds. Although they could have easily climbed over the wall, they never did. They were scared of the castle owner, Madame Franco, who lived in the big tower. She was the village aristocrat, related to General Franco, and nobody messed with her.

Eventually the gang got bored with yelling at us and they left. We headed towards the castle.

“Your mouth is going to kill us,” I said angrily. “Why’d you have to say the one English word they can understand?”

“What?” said Jon.

“Idiot…idiot,” I repeated, saying it with a French accent.

“I don’t care, they are idiots,” said Jon.

“This is so stupid,” I cried, shaking the icy dirt from my shoes. “Every day the same stupid game.”

The next day Jean Pierre, a skinny runt of a kid whose hair grew in strange wispy tufts of mousy brown, jumped on my back during recess and started pulling my hair with all his might, just like he always did. He was obsessed with tormenting me. Perhaps he wanted to make my hair look like his. If I could have killed him I would have, but I didn't know how to kill anyone, I didn't even know how to beat a person up. Such actions didn't come naturally to me. But I was learning.

Every day at recess I tried to keep Jean Pierre off of me by keeping my back to a wall, always watching to see where he was. He would look at me fixedly from across the playground, his pixie eyes filled with challenge. He was always dirty, in old sweaters with holes in the elbows, holes in his shoes. I'd try to keep my eyes on him, but eventually, without realizing it, I'd be distracted and look away, just for a mere few seconds, and when I'd look back again, he'd be gone. That's when it would happen. I'd whirl around in a panic, but I wouldn't see him. Suddenly, he'd be on my back, yelling with triumph, and once there, it was impossible to remove him.

I didn't understand why. Where was the logic, the reason? What did he gain from it? What bizarre thought process had gone through his mind in order for him to think up this torture? And why me?

The hair pulling hurt so badly that I screamed. It was humiliating. Nobody except Jon came to my rescue. Everyone else just watched with interest to see what would happen. While Jon yanked on the kid and punched him, I reached around and tried to pull him off, pinching him and shaking back and forth, banging him into the side of the school, which only succeeded in hurting me. He was oblivious to pain. My head felt like it was on fire, as if all my hair was being pulled out in clumps.

At last, when I thought I would never get rid of him, he jumped off, laughing, and darted away so fast, I didn’t even try to chase him.

I was red-faced and sweaty, panting hard. In my frenzy to get rid of him, I hadn't looked where I was stepping, and I was splashed with mud up my legs.

I looked around at the kids on the playground. They looked back, smiling and laughing. That was it. All my frustration, humiliation and anger welled up inside of me, rushing from my stomach into my throat and out my mouth. I screamed at them, my body rigid, my hands clenched in fists at my sides, “I hate you! Do you hear me? H-a-t-e you!” I said the word hate in a long-drawn-out ear-splitting growl, as if I were possessed by a demon.

No one said anything back. They just stared, open-mouthed, showing the first signs of real concern, as if before that moment, they hadn't realized that maybe I had feelings, maybe I was a human being, just like they were.

In anguish, I ran up the stairs and into the schoolhouse, slipping all the way, the bottoms of my shoes caked an inch thick with mud. I kept running, into the girls' bathroom, only stopping when I reached the far wall and could run no more. I stayed there, pressed against the wall, crying and crying, wishing I could get out of that prison.

I heard the door open and turned to see faces peeking in at me.

“Go away,” I screamed. “Partez!”

The door slammed shut.

I cried some more, but I was exhausted and running out of steam. No one can keep up that kind of hysteria forever. I slid down the wall and landed in a heap on the floor.

Again, the door opened a crack, and the faces reappeared. I didn't scream at them this time. Emboldened, the door opened completely to reveal all of the girls.

One of them, a nice-looking girl named Nadine, with short brown hair and blue eyes, bravely approached me, speaking softly.

“Je ne peux pas te comprendre,” I said bitterly. “But that doesn't make me stupid!”

There was a commotion, and the sea of faces parted to reveal Madame Petriquin. She actually looked worried and kind.

She made a comforting “Tsk, tsk,” sound and shooed everyone away, except for Nadine. Nadine reached down and helped me up. She put an arm around me, and I didn’t resist. She and Madame helped me out of the bathroom.

After that, the girls never laughed at me again. They began to protect me from the boys, refusing to let anyone bother me. Nadine even invited me to her birthday party, and I had fun. She became my best friend, and I started speaking French more boldly with her encouragement. Although I never completely lost my self-conscious insecurity with languages.

Somehow, from that day on, the world inside that school looked different and my attitude began to change. I decided to try a new approach with Jean Pierre. I didn't think it would work, but I was desperate for things to get better. I had seen him watching me with interest when I drew pictures. The next time he did this, I offered him a piece of paper and a pencil. At first, he couldn't comprehend my meaning. At last, he realized, and his small, pointy face lit up eagerly. He took the pencil, saying merci very nicely, and began to draw. For the rest of the break period, we sat in amiable silence, drawing together. When it came time to go back to class, Jean Pierre gave me the picture he'd drawn. It was of Superman flying through the sky and it was pretty good! I was impressed.

On a sudden whim, I took my colored pencils and held them out to him. His eyes grew wide with disbelief. Timidly, he reached towards the pencils with his small hand, then drew back again, his pale blue eyes looking at me questioningly. I nodded my head and thrust the pencils forward. He took them, thanking me over and over, his face shining like an angel's.

After that, I never had another problem with Jean Pierre. In fact, we became friends. My life in school changed and I began to enjoy myself a bit more. The kids weren't monsters, they weren't heathen barbarians. Well, not entirely, ha-ha. Jon and I still had our problems with Tom and Huck and their gang, but we got tougher and once the novelty wore off, they became bored with chasing us and things improved a lot. Jon’s teacher never got better, though. She really was a monster.

When people nowadays talk about prejudice and it’s all about a person’s color, I know they are missing the heart of the matter. Prejudice is really about fear of the unknown and an inability to communicate. When you don’t understand one another, when you feel like the other person is some kind of alien—and that’s certainly what we were to the kids at that school, and they were to us—all kinds of misunderstandings arise. And if you feed the fear instead of trying to understand each other, nothing will ever get better, it will only get worse.

Honestly, even when things got better, I was still glad when we finally didn’t have to go to that school anymore. At the same time, looking back, I’m thankful that my parents didn’t allow us to give in to our own fears and misunderstandings and stop going before we had overcome them. I learned invaluable lessons about communication, compromise, and even diplomacy. I learned that people could appear different—and it isn’t always a difference of color, it can be class, education, culture, religion—but underneath, we are all basically the same. We all have the same longing to be safe, to have friends, to belong, to be understood.

My sister died of cancer over ten years ago now, and I miss her every day. A few years ago, in order to keep her memory alive, I took my daughter and her daughter, my niece, to visit Echandens and the castle and the village school.

It was an eerie feeling walking through the village streets to the schoolhouse. There it was, the same as ever. I met the janitor who had actually been a student when I was there. I don’t know, maybe he was one of the kids that tormented me. But here he was, a jolly fellow, so happy to see me again all these many years later and proudly show me around.

We went up to the attic where the old school tables were still stored. I sat down at one of the tables and memories came flooding back. My daughter and my niece laughed and laughed; it was so funny seeing me sitting on that tiny chair.

Life is full of unexpected occurrences and children don’t like it when they have to do things that they don’t want to do. It takes some wisdom for parents to know when to give in to their children and when to make them keep going through the hardships. Nowadays, the trend is to coddle kids rather than allow them to face challenging situations. I’m glad my parents didn’t coddle me, although I often resented it at the time.

And I’m so thankful I was able to give my daughter and my niece the experience of traveling back in time to relive those long-gone adventures. Seeing where their mothers had lived, hearing our adventures, brought it all back to life before their eyes.

I love this... so much richness, thanks for sharing this!!

A wonderful tale…thank you for sharing! The castle must have been amazing. As a young girl in the 1960’s, my family stayed in a family run hotel (more like an Airbnb rental, really) in Malta, which was a small medieval castle. My room was in one of the turrets and how I loved running up and down the steep twisting staircase to get to my room. It’s something I’ve never forgotten!