My Life Under Sharia Law

"The most subversive thing a woman can do is talk about her life as if it really matters." ~ Mona Eltahawy

You can listen to me read this story here:

One-time or recurring donations can also be made at Ko-Fi.

I am publishing this on the day of my conversation with Yasmine Mohammed, which starts at 11AM, Pacific Time, 8PM, Central European Time. I hope you will join us.

Before I start my story, I want to say a couple of things. It isn’t always easy for me to write these personal stories. I bare my soul, I let the world see my vulnerabilities. I do it for one reason, to give people in the West, especially women, insight into the reality of living under Sharia law as a Western woman. There are not many voices doing this. If I can open the eyes of one woman to the truth, then it is worth it.

When I went to Egypt, I never dreamed I would be sitting here, writing it all out for others to read. I went with an open heart, ready to embrace Islam. I steer clear of politics or world views in this story. I do that elsewhere. Here, I write about the intimate life in the villages of Luxor. I dig beneath the surface of what tourists see passing through.

It’s amazing how you can pour out your heart and people still refuse to listen. They say, oh, that’s just your experience. Lots of other women embrace Islam happily. Let me tell you, there are hundreds of social media sites where women go to express their pain, the nightmare of their lives. The vast majority are too embarrassed or too terrified to tell their stories except in these private support groups.

After my article, The Lost Foreign Women of Luxor, was published in Egyptian Streets, many women messaged me. I cannot share those messages because it would be too dangerous for them. One woman told me she wished she could tell her story, but if she did, she would not live to see the morning. I also received death threats from men and derision from woke Western women who called me a real “Karen” and accused me of trying to impose my white imperialist colonialism on Egyptian women. I got so tired of their foolishness, their willingness to embrace the fake propaganda spread by Western “influencers” rather than the truth.

Yes, there are women who get married to these men and accept living under the strict rules of Sharia law. But if you listen to them, it doesn’t take long to realize how brainwashed they are. It is no different from joining a cult.

I’m introducing this story with a short explanation of the Muslim Brotherhood by Egyptian activist Dalia Ziada. She is one of the most articulate and knowledgeable voices on this topic. I don’t mention the Egyptian Brotherhood, but it’s important to have this larger picture of Egypt before delving into my story.

The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in Egypt. It is the most dangerous organization because it is their ideology upon which other extremist groups, such as al Qaeda, was founded, with its main goal to establish an Islamic Caliphate. This Caliphate should rule all people--meaning you and me, everyone, everywhere.

So, I would like you to go into reading this with that knowledge in the back of your mind.

I went to Egypt with the perception that it was the most progressive nation in the Middle East, and I know a lot of people are under the same impression. My story shows how deeply embedded this cultish ideology is in everyday life. I don’t really know how it can be rooted out. But one thing I do know is that we don’t want that ideology spread to the West as it is doing now.

With that, I hope you enjoy my story.

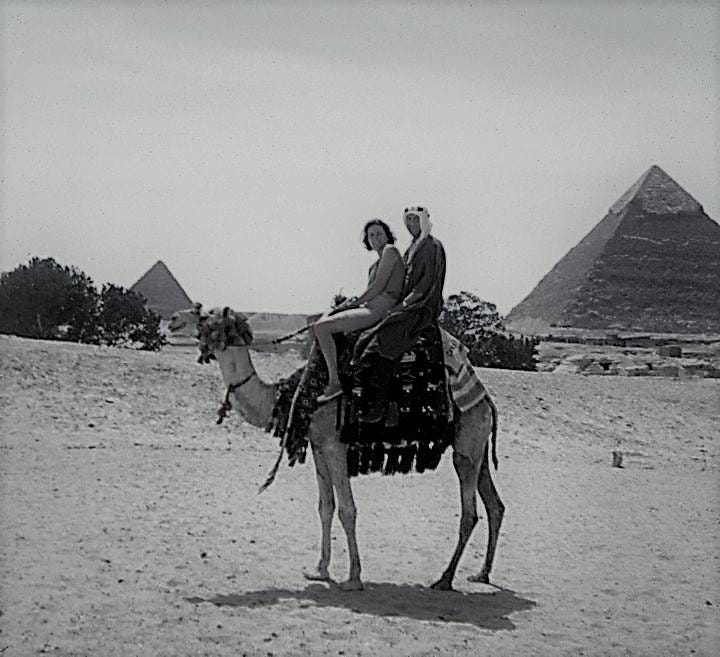

I landed in Luxor, Egypt at the end of 2017, excited and eager to embrace everything about this magical land, including Islam. I’d fallen in love with Luxor as a child, when we had left dangerous Cairo, just days before the 6 Day War, and driven down to the peace and quiet of this ancient city. All the tourists had fled, and we were treated like royalty. We even got a deal at the Winter Palace, on the banks of the Nile.

Sailing on the Nile in a felucca, listening to the stories of a Nubian sailor, his flowing white robes and turban in contrast to the blue of the sky and black of his skin, I felt as if I had gone back in time to the stories I loved about Arabian princesses and Sinbad the Sailor, magical lamps and genies. Generally, I’d had enough of museums and old buildings, but the Valley of the Kings and Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb were nothing like that. Luxor Temple in the moonlight. What could be more fantastical.

I resisted my dad’s insistence that Islam was the religion of Satan. All these people desperate to sell us something because they were poor, the women so mysterious behind their veils, they couldn’t all be agents of Satan. I mean, that was ridiculous. And not at all nice!

Yet my dad’s frustration was valid; I saw how he constantly had to ensure we weren’t cheated and lied to. He was angrier than I’d ever seen as he argued with taxi drivers and staff at hotels. My dad was not one to lose his temper, this was the only time I saw him come close, not once but over and over.

We just happened to arrive in Cairo days before the 6 Day War. There we were, in a bright red VW van with a big, obligatory USA sticker on the back window. Men roamed the streets with guns and knives, whipped into a frenzy by Nassar’s voice screaming on loudspeakers, “Death to America and its stooge Israel!” and the throngs screamed along.

It wasn’t like that in Luxor. Everything seemed peaceful after the chaos of Cairo. But it was the same, my dad assured me. Beneath the smiles, Muslims were all the same. “You cannot trust them. They believe we are infidels, worthy only of death,” he said.

I’ve told this story before, but just to recap for those who don’t know, we ended up escaping out of Egypt, crossing into Lebanon and then driving over the mountains of Syria into Turkey just 36 hours before the borders were closed. Later, we found out that another American family hadn’t been so lucky. Their car had been set on fire as they tried to escape a mob. Of course, there was no internet, no social media back then and we never found out if they survived.

So many years later, I thought surely things were different. In 2014, I’d been in Istanbul, my favorite city, when one day, sitting in a cafe on Istiklal Street, a crowd of people ran by, protesting the war in Gaza. I joined the throng and ran with them. Who wouldn’t have sympathy for the Palestinians?

Surely, I thought, places like Luxor had remained untouched by the hate and controversy, just as it had been in my childhood. Getting off that plane so many years later, I truly believed, as my traveling to other countries had proved, that people around the world weren’t that much different from one another. It had to be the same in Muslim countries.

And so, I was excited to return to a place I loved, ready to embrace everything about the culture and religion. Like so many Westerners today, I thought I knew what I was talking about. Nobody could have convinced me otherwise. And yet, within me there always remained a nagging doubt. What if my dad was right? The only way to find out was for me to go there and experience it for myself.

I’d been traveling the world for about four years before I found my way to Luxor. My kids were all grown up and independent. Finally, I had the chance to become the gypsy I’d always wanted to be, living a simple life, going where the fancy took me.

In Costa Rica I’d met a Canadian woman, I will call her Sarah, who’d gone on holiday to Luxor. Within three weeks she was married and living in a villa that she and her husband, Ali, were fixing up into an Airbnb. The bottom floor was finished, and she invited me to stay there.

That was all I needed, an invitation from someone I knew who lived in Luxor. I was intrigued that Sarah had so suddenly gotten married. She was an independently minded older hippie with long white dreadlocks who had never been married and had seemed perfectly happy with her freedom. Now, suddenly she was married, and to a much younger man, it was obvious to see from the photos, and to a Muslim, no less. What had happened? I was intrigued.

Sarah picked me up at the airport and took me to the villa, situated in the villages along the banks of the canals. It was really nice, especially for the price of $300 a month.

I settled in and before long, she and Ali took me around to see the sights. Every day, I ran through the villages, down to the Nile, the people finding me a strange sight, but smiling and waving. Boys started running after me, laughing and joking. One boy raced me on his donkey.

I was teaching English online in China at the time and despite a sketchy internet, everything seemed to be working out well.

I loved my life in Luxor. Within the first week, I felt so at home, I thought perhaps this could be the place I would settle down at last.

One late afternoon, Sarah took me and a friend of hers to a rooftop restaurant owned by Ali’s brother, Mohamadin. That was when I first saw Mohamadin, balancing a huge tray of food, gracefully walking towards us in his bright blue jellabiya. I have to say, he caught my eye. But he seemed to know Sara’s friend, she was clearly flirting with him, and they spent time talking together.

From then on, I went often to the restaurant, with its delicious food and stunning view of Luxor Temple across the Nile. One late afternoon as I sat drinking a mango smoothie, Mohamadin asked if he could join me.

We sat together and talked for a long time as the sun set. I was pleasantly surprised by his command of English and his princely manner, polite and calm, unlike the dramatic loud voices of most of the men. I knew nothing about the “bezness” of Luxor.

Luxor is known as the capital of bezness in Egypt. The men are adept at flattering and seducing women into marrying them and then bilking their wives of all their money. This is an art passed down from father to son. Most of the villas on the West bank are built with the money of foreign women, thanks to bezness.

Of course, I couldn’t help but notice the old ladies walking the streets, holding hands with their young men. I thought, aren’t they embarrassed? Don’t they know how silly they look? But beyond that, I didn’t think too much about it.

There’s a saying in Luxor, MMD, or “My Mohammed is different.” Every woman thinks her husband is different from the others, that he really loves her, no matter how old and, let’s face it, ugly she may be. It’s sad, but then, most of these women had never been told by the men in their home country that they were beautiful. They had never been given so much attention. Back home, they would no doubt be living alone, forgotten by their families and friends, if they even had any.

Once married, their Egyptian husbands make sure they are cut off from their former lives. In the beginning, they don’t see the danger signs, they are so enamored. But in the end, they become prisoners of Luxor.

Mohamadin started looking after me. With his best friend, nicknamed Bango, they owned a taxi boat. Whenever I needed to cross the Nile, they took me. If I needed help with the internet, they made sure it was all taken care of. Anything I needed, they were there for me.

For hours, we talked at a favorite restaurant, Al Beairat. Mohamadin told me how he had grown up poor in a village. He explained his life, how hard it had been, how he had learned English from tourists, how slowly but surely, he had built up a good business, with the taxi boat and the restaurant. He said that he owned the villa where I was staying. He had made a deal with Sarah that she could live there for five years as long as she put her money into fixing the villa up and running it, doing the advertising on social media. I knew she worked online and didn’t have a lot of money. It seemed an odd deal, what would happen to her after five years?

But that wasn’t my problem. She seemed happy. And indeed, her life seemed idyllic. Mohamadin and Bango also explained that they owned another property they were fixing up. I thought, wow, they must be well off. I was impressed with how hard they had worked to get to where they were today.

I spent more and more time with Mohamadin. We sailed the Nile in a felucca, just as I had done as a child.

We rode horses across the desert, visiting the Coptic Monastery that lay beyond the villages, burning under the hot desert sun. I didn’t know then that this was where the foreign women of Luxor were buried, dumped into shallow graves, their stories lost forever among the bones of thousands of years.

As we left the monastery, Mohamadin took off at a gallop on his Arabian steed, and I followed after him. He told me later that he well knew what he was doing, he wanted to make me love him with that ride. I wouldn’t have gone so far as to call it love, but I did love the romance of the situation.

One night as we sat outside at Al Baeirat, Mohamadin confessed his love for me. Now, I have to tell you, I didn’t believe him. We’d only known each other for a couple of weeks. I thought to myself, this is just what happened to Sarah. Like Sarah, I was much older than Mohamadin, but I was healthy and fit, I could have probably outboxed and definitely outrun many of the men, who sat watching football and smoking endlessly. I knew it was a game he was playing, but there was no question we were attracted to one another, and I thought maybe I was in for this adventure.

There I was, drinking a beer with this intriguing man, moonlight twinkling like diamonds on the Nile, and I thought to myself, I could learn so much if I do this. No man had interested me in years, but this man did. Not just the man, but the entire situation. I had faced years of abuse in my first marriage, something I’ve written about elsewhere. Because of the abuse, I’d developed the ability to detach myself emotionally from situations. So even though my emotions were played upon by Mohamadin, a part of me remained wary and I have no doubt that my writer’s curiosity and my ability to disconnect saved me from becoming too entangled.

He asked me to marry him, and I wasn’t as shocked by it as I should have been. I had strayed far from my Christian faith at this point, and I had no problem entering into the relationship. If we had been anywhere else in the world, we could have had an affair, but that wasn’t possible in Egypt. There is no way to be in a relationship with an Egyptian man except by getting married. In fact, a man cannot even enter a woman’s apartment alone. He can go to prison if he does. So can the woman. Many months later, a foreign woman in Cairo was thrown from her balcony and killed by the men who lived in the building because she had allowed a colleague into her apartment to have a cup of coffee.

Mohamadin told me there was one thing that might be a problem for me. He was married to an Egyptian woman. Again, I was shocked but not as much as I thought I would be. Somehow, in Luxor, these things seemed quite natural.

And they were.

After all, Muslim men could marry up to four wives. He told me about his wife, how it was an arranged marriage, he didn’t love her. Of course, that’s what they all say, right? Within the first month of marriage, she had become pregnant, which was her obligation, and had born a son. But then, she had almost immediately become pregnant again—with triplets, all boys. This was something Mohamadin had never expected. He loved his children, but he was now stuck with this huge responsibility that he had never imagined he would have so quickly. He was extremely unhappy and weighted down with worries. This, I could understand.

He explained that according to law, he had to inform me that he was married, and he had to inform his Egyptian wife of his desire to marry me, and she had to agree.

“And did she?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said.

I found out later that most wives agree since they can expect a better standard of life out of the arrangement, once their husband starts scamming the foreign wife. Even if they don’t agree, it didn’t really matter, there is no way to stop their husbands from doing what they want.

Most of the men who play these games with foreign women lie about being married, telling their foreign wives that they are single or divorced. The entire family is in on the scam so even if the new wife goes to the village to meet the family, they will claim the woman living there is a cousin, or something, when it is really his wife. The lies are endless. But Mohamadin didn’t lie to me. In fact, he assured me he wanted me to be a part of his family. I met his sons, and they were so sweet and adorable. I enjoyed spending time with them.

I think he told me the truth because he wanted to register our marriage, so it would be more official. Most Orfis are just pieces of paper. If they are torn up, you are no longer married. I suppose I am still “married” to Mohamadin, but beyond Egypt the marriage is meaningless.

I thought about Mohamadin’s proposal. If I was going to embrace Islam, this was part of it. And I was insanely curious. When would I ever get a chance like this again?

A part of me felt like a spy, going undercover. I have no regrets that I said yes to Mohamadin’s proposal. Because I went as far as I did, I am able to speak with authority and warn other women about the truth of living under Sharia law.

There was one thing that I made clear to Mohamadin. If he ever disrespected me, even if he just yelled at me, that would be the end. Over the course of our many conversations, I had told him about my abusive first husband and how I had completely changed my life, trained as a full contact boxer and kick boxer, trained in weapons and had trained other women to defend themselves. I assured him that I was the last person he wanted to try and push around. He said of course, he would never treat me with anything but respect. And I have to say that he kept that promise, until the very end, when everything fell apart.

I can tell you one thing. Mohamadin had no idea what he was getting himself into when he married me, even with my very clear warning. Although Mohamadin was intelligent and observant, he had never been on a plane, he had no concept of the world beyond the borders of Luxor. He didn’t know about American women like me, or how free I was to do exactly what I wanted and how hard I had fought to get that freedom and how I had no intention at this point in my life of giving it up. I would fight and die rather than do that.

We were married on a sailing boat called the Amira Sudan, a sandal that is larger than a felucca but smaller than a dahabiya. A fun, simple party, with Mohamadin’s friends witnessing our Orfi marriage contract, a lawyer showing up for a few minutes with the documents for us to sign, to make it official. They said I needed to choose an Arabic name, and I chose Sama, meaning sky. Mohamadin’s friends called me sister and vowed to protect me forever.

As the evening wore down, I looked across the Nile at the Winter Palace thinking of my childhood self all those years ago. On a night just like this, I had lain on the balcony staring across the Nile at where I was now. My family had pulled mattresses onto the balcony to escape the heat, and we had looked up at the stars together marveling at the beauty of it all. It felt as if my childhood self was now staring back at me over the years, giving her blessing. You will find out everything you want to know, she seemed to be saying.

I thought of my dad and the conversations we’d had about Islam. If he were still alive, I knew how angry he’d be at my marriage. I felt a momentary twinge of concern, but it quickly passed.

Once Sarah found out about our marriage, her attitude toward me changed from nice to hate-filled. Unbeknownst to me, all this time, she had been plotting for her friend to marry Mohamadin. I only found out later how women like Sarah, who fully embrace their lives in Luxor, will often pimp out a friend from back home, and if they can get the woman to marry the man chosen for her, then they get a cut of the profits. I had ruined her plan. The layers upon layers of deceit in Luxor are impossible for a newcomer to unravel.

Looking back, I hope Sarah is still happy there, I have no ill feelings towards her. I remember her saying one evening before my marriage, as we sat having coffee on the roof, how she had never had a family. Now, she was part of a big family. She said this with a lot of love toward her new family. The men in Luxor know how to work on the weakest part of a woman, promising her things that will repair some pain or give her some emotional attachment that is lacking in her life. I could see how Sarah would find that connection hard to resist and would do anything to protect it. Last I heard of her, she had reverted to Islam and now wears the full Muslim hijab and robes.

As long as these women were willing to accept the scamming game, they had some sense of security. But when their money ran out or the scams failed? They were thrown out with the garbage. This I saw happen over and over again, once I figured out the truth of what was going on.

But I didn’t know it then. All I knew was that Sarah was livid at me for marrying Mohamadin “behind her back” as if I had plotted to destroy her life. She told me I had to get out. I was completely baffled.

“How can she do that?” I asked Mohamadin. “If you own the villa, shouldn’t she be the one who has to leave—I mean, I don’t want her to leave, I don’t have anything against her, but how is this okay?”

“Habibty, but I have a contract with her for five years,” he said, calmly and reasonably. “Anyway, you don’t want to live here anymore, do you, we won’t be happy.”

I moved onto the Amira Sudan. I still didn’t get why he had to give in to Sarah. What I didn’t know at the time was that he wasn’t giving in to her, he was obeying orders from the mafia lord who was probably the real owner of the villa. Over the course of my time there, I discovered that men like Mohamadin and Bango, who claimed to own villas were just managers. Their job was to woo foreign women into putting their life savings into building these villas. The women would sign contracts thinking they owned the villas, but they didn’t.

Everyone was in the on the scam, the lawyers, the real estate agents, the police, everyone. Often, the men would sell the same property over and over to different women, each one thinking she owned it. If the women gave any trouble or ran out of money, their lives were made so miserable, often with physical violence, that they left the country, if they could afford it. If they couldn’t, they lived on in poverty unable to ever escape. After I met Gitte, she told me there is a saying in Luxor, a woman can only leave Luxor with the skin on her back. Nothing else.

Mohamadin didn’t ask me for any money for a property, so I never thought about being scammed. I was enjoying my life. I loved living on that boat. It was so romantic.

I enjoyed going across the Nile to the souk and buying fabric to make my jellabiyas, the long, flowing dresses Egyptian women wear. Men wear their own version, and I would buy fabric for Mohamadin, too. We would then go to the ladies who sewed them for me. Mohamadin’s was sewn by a man. To me everything looked like a painting. As an artist, I loved the atmosphere, the colors, the mystery of life in Luxor.

I really liked the seamstresses; they were more independent than most of the village women and they were so much fun. Again, I wished I could talk to them, but none of the village women spoke English.

My niece came to visit, and she was treated like a princess. One evening when we went to Karnak Temple to see the light show, a terrible dust storm arose. The wind began to howl, and the great columns became obscured, as if the gods were angry at us for disturbing the temple.

The sand bit into my skin like a million tiny needles and I wrapped my scarf around my face, telling my niece to do the same. I grabbed her hand, and we turned and ran for the protection of a small shed in the parking lot. The others, who were from a German tour group, quickly followed, and we all huddled together. Eventually, vans came to take them to their hotel, and they dropped us off at the ferry. A long line of people was waiting, but no ferries were being allowed to cross. It was too dangerous with almost zero visibility. If a giant cruise ship came along, they wouldn’t see the smaller boat.

I called Mohamadin and before long a taxi picked us up and took us to a quiet spot further down the banks of the Nile. We waited in the taxi until Mohamadin and Bango’s taxi boat appeared out of the gloom, with Bango’s brother guiding it. We got in the boat and started across the water that had become a roiling sea. We were alone out there, and I felt like a ghost in a dream world. I thought of the ancient pharaohs and the frightening “River of the Dead” or “Amentet,” that they crossed to reach the afterlife. My niece seemed to be enjoying the adventure as much as I was. She was studying to be an archeologist.

Once back at the Amira Sudan, I was thankful to see Mohamadin waiting for us. The experience made me trust him more. He had orchestrated our return flawlessly, while the crowds were probably still waiting for the ferry or had given up. We went below to our room, and, yes, we had a passionate night, and I feel asleep to the sway of the boat and the moan of the wind. The next morning dawned clear and bright. Up on deck, sand covered everything, piles of sand. Men came to clean it all away.

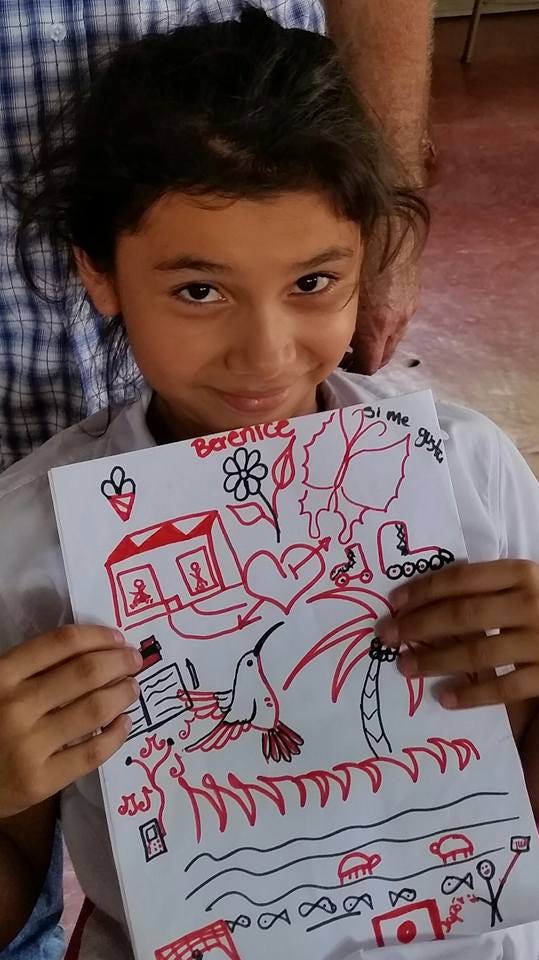

In the summer, it was way too hot to live on the boat and I moved into a villa with a lovely garden. That’s when I first put up my boxing bag. There are no secrets in villages and before long curious children were climbing the wall to peek over the top and watch me punch and kick the bag. Soon kids were banging on the gate, demanding to come in and try it. It was all boys at first, but slowly, girls shyly started to arrive. I hadn’t come to Luxor to start a boxing club for girls. But over time the idea took shape. Still, it would be many months before I would set up the classes.

In the meantime, I was having a great time, teaching online, writing, and going out to restaurants, weddings, sailing trips. In the evenings, we had barbeques with Mohamadin’s small circle of male friends. There were no women, of course. I never got to know any Egyptian women. They all stayed in the villages and none of them spoke English.

Over the course of a few months, Mohamadin and I watched the entire series of Game of Thrones. He was completely fascinated by the show. He remembered the plot and understood parts of it better than I did. He told me stories of ancient Luxor, of the black-market treasure trade. What it was like hustling to make money from tourists as a teenager. Once out of school, there had been a Swiss family that he had worked for as manager of the villa where they stayed. A nice family that had taken him under their wing. But the father had come on to Mohamadin, or at least that’s what he thought. When Mohamadin was invited to go to Switzerland, all expenses paid, he declined. Ever since he had always wondered if he had turned down a golden opportunity.

In all fairness to these men, I saw how circumstances pushed them into becoming nothing more than male prostitutes, although they would never see themselves that way, insisting it was the foreign women who were the prostitutes. If you grew up in the villages and you wanted to make money, you got involved in the bezness.

And then, overshadowing every aspect of life, there was Islam. One of the first words I learned was haram.

“It is forbidden!”

Mohamadin and I used to joke about that. I’d say, yes, I know, “It is forbidden” in a deep threatening voice and we’d both laugh. But the reality is that it wasn’t funny at all. If you are a tourist, it’s all very enchanting. You don’t see how Islam controls every aspect of life.

The call to prayer happens five times a day, waking you up in the middle of the night, never letting you forget that Allah was watching over you. In the morning, the cafe televisions are all set to the same station reciting the Quran, endlessly in a hypnotic voice. Children attend classes in the mosque, where all they do is recite the Quran, over and over, never an explanation, just accepting what it says like zombies. Then there are the tedious washing rituals and bathroom rules that I really didn’t understand. If my family back home had worried that I might convert (revert Muslims would say) to Islam, they needn't have. It was the last thing I wanted to do.

But if you are born Muslim, you can never leave Islam. I was told this in no uncertain terms. If you denied your faith, you were killed. But who would leave anyway? Islam was the one true religion.

Mind you, these men of Luxor were not extremists. That’s what I want those who are reading this to understand. They were ordinary Muslims. This is what it means to be a Muslim in an Islamic country, living under Sharia law. The religion itself is extreme. Mohamad’s life was one of lying and cheating to infidels. This is the example the men of Luxor followed.

When talking about the 6 Day War, I was told that Egypt had won, not Israel. That was so obviously false, yet I didn’t dare to disagree. Wars with Israel were not a topic to argue about. Every so often I caught the undercurrent of hatred for America and Israel, but it was mostly kept hidden from me. But every day that I went out, if I was on my own, I encountered disrespectful looks and words from men and boys. A woman should keep her eyes downcast, she should cover her head, but I did neither of these things, and I was no longer a tourist, I lived there. Once a group of boys yelled at me and I understood the word “Nazi” repeated over and over.

Mohamadin and his buddies claimed to be devout Muslims, but they were quite the sinners. They drank, they smoked weed and if they were sitting down, they were smoking cigarettes. They were initiated into sex with whores, taken there by their fathers. When we got married, Mohamadin got tested for STDs. Most men in Luxor would never do this, but he did it on his own before I even asked him to. I hadn’t had sex for years, by the time I made it to Luxor, I truly thought that was it for me, so there was no danger of me giving anything to him. And he assured me that the only woman he had been with was his wife. Of course, she hadn’t had sex with anyone else.

“Habibty, when would I have had time for sex,” he told me, and this seemed reasonable. It was only recently that he had finally been able to get out of the house since his triplets and his wife had all been very fragile after the birth and needed a lot of care.

For most of the men, though, they would have sex with anyone, some of them were well known to have sex with gay men, and they would even sell young boys to male tourists. When it came to infidels, anything was acceptable if it meant making money off of them.

I saw how the men spent the evenings roaming the corniche looking for tourists to seduce. I came to recognize the foreign women who lived there, trapped in marriages that they could not escape, eaten alive by their vampire husbands. They formed alliances amongst themselves and then fought like cats. Many were alcoholics, drug addicts, having been led into addiction by their husbands as a way to control them. The British women were among the most unpleasant, treating one of the hotels, El Gezira Garden, as their “club”. They paid a fee to feel superior from everyone else, to swim in the pool and then lie about on chaise lounges and gossip as they drank tea.

I used to stop by the hotel for a fresh squeezed orange juice after my run and I had to be careful not to unknowingly sit on one of their chairs. Because, after all, they paid for it, and I didn’t. One time I overheard a woman talking to someone on the phone, advising her to leave her husband who had beaten her up yet again. After she hung up, she rolled her eyes at me as she took a puff on her cigarette and said, “She’ll never leave.”

“Where could she go anyway,” I said.

She shrugged. “There’s no escape, not really.”

My life wasn’t like that, and I knew it never would be. I didn’t have these issues with Mohamadin and if I did, I would simply get on a plane and leave. I had a life beyond Luxor, something many of these women didn’t have. I had children that I loved and that loved me back. I had friends, colleagues, a job. My family and many of my friends might not exactly be happy I was living in Luxor, married in such a crazy fashion. But they still loved me, and I knew my sons, one of them 6’ 8” and the other one 6’ 5” would be on a plane in a second if they thought I needed them.

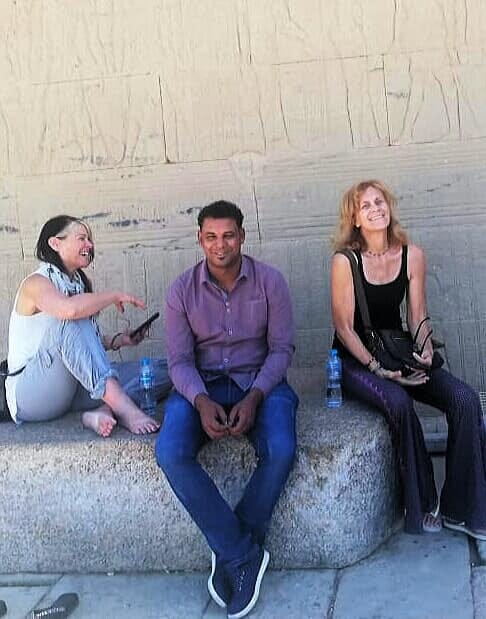

One friend, Leta, a tough trainer in the gym like me, came to visit twice. We had the time of our lives. We went down to Aswan with Mohamadin and Bango. Bango started working on her to buy a dahabiya, but she was never fooled. She enjoyed her adventure and then went home.

The important day came when I went with Mohamadin to his village home to meet his family. His father, his two other brothers, his petite, pretty wife, and his mother, a large boisterous woman whom Mohamadin adored. This is common with Muslim men. The sons are spoiled by their mothers while the daughters serve their brothers until they are married and then they serve their husband, and their mothers-in-law. Mohamadin’s wife and mother made us dinner, served it to us and then disappeared. I asked if they would join us, but absolutely not. This didn’t make me feel a part of the family. It felt like it was orchestrated to make me think it was like that, but it wasn’t. I would have liked to talk with his wife, but that was impossible.

I was shocked at how poor the house looked inside. The kitchen was a hovel, with the most basic, ancient appliances. The floor was dirt, the rooms were dark and dreary with old furniture, some of it so wobbly it looked useless. Mohamadin and his wife and children lived two floors above. He explained how terribly hot it was on the upper floors in the summer, without air-conditioning. I wondered how he could let his family live like that when he came to stay with me on those hot days in my airconditioned villa. Why did his family live like this if he owned two large villas that he was working on, and he had shown me all the farmland his family owned. He was richer than most Americans when it came to property.

But he explained that he used every penny he had to fix up the properties so that one day he could lease them out. And the farmland couldn’t be used to build on. It had to remain as it was. He always needed money. But he never asked me for any. I didn’t mind paying for our dinners or paying for my own villa. I liked my independence. It was a new thing for me, to be the one with the money, to be the one with the power in the relationship. I didn’t have a lot of money, but a small amount went a long way in Luxor.

I was in a unique position to find out what these local men really thought about women. On nice evenings as we barbequed and drank beer, Mohamadin and his friends opened up to me and I found out shocking truths. One time, I asked them why they were allowed to have sex with other women, but their wives were not. They were deeply offended by such a question. Their wives could never do that.

“What would you do if you found out you wife was unfaithful?” I asked them.

They all answered the same thing. “I would kill her.”

I thought they were kidding, but even if they were, what sort of a joke was that. But the thing is, they weren’t kidding. Women stayed in the villages with the children because that was where they belonged. Mohamadin’s wife had an old phone with no internet. She was not allowed access to the internet where she could be tempted with all sorts of sins. Never mind that these men were all on dating aps and trying to find as many foreign women to marry as they could, lying to each one, behaving in the most reprehensible manner. Some of them had multiple wives that they juggled. Women that came for a month or two a year and gave them an allowance for the rest of the year, thinking they were the only one. Some of these men became quite wealthy like this. But they always were careful to hide that wealth so women would feel sorry for them.

Mohamadin spoke with derision about his own wife and how all she did was watch Egyptian soap operas.

“What else can she do,” I said, beginning to lose respect for him.

I started reading Egyptian women writers like Nawal El Saadawi. A quote of hers is at the top of Break Free Media.

“They said, 'You are a savage and dangerous woman.' I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous.”

When I found out that 90% of girls in Egypt are still subjected to female genital mutilation, that was the beginning of the end for me.

I asked Mohamadin, “If you had a daughter, would you cut off her clitoris?”

Without a second thought, in fact, seeming puzzled by the question, he said, “But of course.”

Girls were dirty otherwise. They were not suitable for marriage. They would be too sex crazy. Not calm and reasonable. I tried to explain to him why he was wrong, how it took away a woman’s pleasure, how it caused so many health problems. He listened but I was beginning to realize that the way he listened was not to gain information that might enhance his life or open his eyes, it was just a way for him to become better at lying to women.

I was disappointed. I had hoped he’d see the value of widening his world. I had talked to him about his children one day coming to America to study. My children could come here and visit. He had smiled and nodded his head. But now I realized he didn’t see it at all. His thinking, like most of the men there, did not plan long term. It was all about the hustle.

There are men who get married to obtain a visa so they can live in the country of their wife, scamming her and sending the money back to their family in Egypt. But this wasn’t the case with Mohamadin. All he wanted was to rise as high as he could on the ladder in Luxor.

All of this came to a head around the time when Mohamadin and Bango finally tried to scam me with a real estate deal. It was at least a year and a half into our marriage when I was told about the property that they wanted to buy. It was $50,000 and they had all but $16,000 of it. Not a very large amount, all things considered. If I invested it, we could all be equal partners, they said. I went to visit the property, and it was really beautiful although it needed a lot of work. It had two small domed houses, a garden, rooftop terraces and a large property behind that could be transformed into a gym and a fruit and vegetable garden.

One night they came to my villa with a pile of cash, they said it was about $40,000. They counted it all in front of me, with two other witnesses, in a very serious fashion, and then took off, Mohamadin and Bango on Bango’s motorcycle with the bags of money to give to the man from which they were buying the property. It was one of the strangest nights I’ve ever had. Watching them disappear down the road clutching those bags of money, it seemed almost comical.

I moved into the property, helping them to clean it up. We discussed the possibility of turning it into a writers’ retreat. I asked the advice of family and friends, but I knew they would tell me not to do it, and sure enough, not a single person said it was a good idea. My emotions told me the opposite, while my brain told me they were right.

From the day Mohamadin and Bango showed me that pile of money, they started applying pressure that I had to come up with the $16,000. They had paid, they said. Now it was my turn.

I began to feel increasingly uncomfortable. I had asked the advice of everyone I knew, and nobody wanted me to do it.

“But you promised,” they said.

No, I hadn’t promised, I countered. Nobody makes such a promise without thoroughly evaluating everything. I told me that they had never given me the name of the person who they were buying the property from, I couldn’t find advertised with either of the two real estate agents in town. I had heard the horror stories of men selling and reselling properties over and over.

They started to lose patience. They said if I didn’t come up with the money by the end of March 2018, their contract would not go through, and they would lose everything.

“But I haven’t seen your contract,” I said.

“Habibty,” said Mohamadin (a term that was beginning to annoy me), “we make this contract by honor. And we cannot tell the owner about you, if he knows a foreigner is investing, he will raise the price.”

“But you already paid at least $40,000, you say you have a contract by honor, so how can he change it?” I countered. Nothing added up.

“You don’t trust us,” they said.

That was true. I didn’t trust them. “So, you want me to sign a contract that I haven’t seen, after I send you money? Nobody just sends money like that without assurance of what it’s being used for,” I said.

They became more aggressive.

I didn’t understand. How could I not trust them after all they had done for me. If I didn’t give them the money, they would lose their reputations, they lamented. No one would ever do business with them again. They would never recover.

Sadly, at the same time, Mohamadin’s mother was in the hospital and dying. He was devastated and distracted by his obligations to his family. For that reason, I forgave him for his frustrated attitude. Then, one day, he came to the property with his arm in a cast and a sling. A tuktuk had run into him on his motorbike as he left the hospital, and his arm was broken. Everything was going wrong for him.

My daughter is a lawyer, and she came up with a brilliant plan. “How about you give them a contract,” she said. She drew up a simple two-page contract for Mohamadin and Bango to sign.

“If they’re honest, they’ll sign it, that’s how you’ll know, not that you don’t already know,” she said.

It was a great idea. By this point I was in fighting mode, and I was going to win this battle, one way or the other. I was going to find out exactly what was going on.

The contract simply stated what we had agreed upon, that the $16,000 would go towards buying the property and that I owned one third of the property. These men are obsessed with contracts, the Orfis and the real estate contracts that they convinced women to sign. I don’t think this had ever happened to any man in Luxor before. No woman had ever presented them with a contract.

When I gave Mohamadin and Bango the contract, written in English, that they would have to translate into Arabic and then sign, I never saw two such shocked faces. They looked as if I had punched them both in the nose.

Once again, very reasonably, I explained that this was a business arrangement. Nobody should be naive enough to give money without some sort of assurance of where the money was going and the ownership that had been agreed upon. Of course, by this time, I knew that plenty of women were that naive. I just wasn’t going to be one of them.

Finally, they grasped what I meant. Whatever remnant of civility they were still holding onto fell away and they went ballistic.

“How can you do this to us,” they yelled. Even Mohamadin’s face changed and he now looked at me with hatred.

Well, if I had wondered about trusting them before, I knew I couldn’t now. It was beyond question that the whole thing was a scam. I let them rant.

I was ruining their lives. My daughter and I were liars and cheats. We were dirt. We were evil.

I had never heard Mohamadin yell or even raise his voice. Now he screamed at me, “I curse the day I met you! Look at me. You ruin my business. I broke my arm. My mother is dying. It is your fault. You with the evil eye!”

He went into the garden and picked up a rock and threw it viciously at the wall, something I had a feeling he would rather have done to me but didn’t dare. He began pacing, muttering to himself in Arabic as if he’d lost his mind. Bango was worse. Eyes filled with hatred, lips curled in rage, he shook his fist menacingly in my face. “You will be sorry for this!”

I told him to get out. I went back into the house and locked the door, my heart thumping in my chest. Eventually, I heard them both leave and I went out and locked the gate.

I called my daughter and told her the deal was off. “Good,” she said. She couldn’t resist adding, “I told you so.”

That day, I got a plane ticket back to Phoenix. But I would have to wait five more days before the flight. My son back in Phoenix found out exactly where the property was on a satellite image. He was ready to get on a plane and rescue me, but I said, don’t worry, I can take care of myself.

The next day, Mohamadin’s friend Hassan came to tell me that Mohamadin’s mother had died. Hassan tried the nice approach, telling me now much Mohamadin loved me, and I should still consider buying the property. I told him I had bought a plane ticket and I was leaving. He couldn’t believe it. I don’t think any of them ever considered that I would leave. They still thought I would back down, that they could charm me once again.

I was sad about Mohamadin’s mother. She had been kind to me. We had danced together at the wedding of Mohamadin’s cousin. She had hugged me with what seemed to be love. Mohamadin had often brought me bread that she baked just for me. But they were all such good actors. It was disconcerting how easily they could lie and so patiently.

I think in large part the death of Mohamadin’s mother may have saved me from worse revenge. Because of Mohamadin’s obligations, he had to stay at the family home for four days of mourning and it would have been inappropriate for him to plan dastardly deeds on me.

It was a huge relief to know the truth at last. The proof had been building up for a while. I had found out what I had wanted to know when I came to Luxor. It was a terrible truth beneath a web of lies.

At night, I made sure the gates were locked. I slept with a stick by the bed, thankful for the coils of barbed wire at the top of the walls. Bango came by one day, pleading to be let in and I opened the gate. He paced back and forth in the garden saying he would give me one last chance to come up with the money.

“Really, you’re going to give me one last chance,” I said.

He tried again to make me feel guilty, the same old story, how I was ruining their lives, their reputations. I realized that in a way, I was. It was embarrassing for them to have put so much time and effort into scamming me—over a year of waiting for the right opportunity—and it hadn’t paid off. Even worse, I had turned the tables on them, demanding they sign my contract. They would probably never hear the end of it from the other men in the cafes as they sat watching football in the evenings. That’s what they did, gossiped among themselves and boasted about the scams they had pulled off.

When I told Bango it was no use trying to convince me, he turned menacing again. He was a big guy, the heavy of Mohamadin’s gang, and I wondered how I could have ever thought he was a nice person. “I will not let you ruin our lives,” he hissed in my face.

In my best moudira voice, meaning boss lady, I told him to leave, and he did.

From that day on, if I passed any of Mohamadin’s gang when I went out to get food or to sit by the Nile, I felt their hostility. The men who had promised to protect me at our wedding now became my enemies. I couldn’t wait to get out of there.

The night before I left, I climbed onto the rooftop terrace for one last view of the moon rising above Luxor Temple. Across the street a family was on their rooftop, and they smiled and waved at me. The muezzin made the call to prayer and the sound floated across the Nile. Perhaps I would never come back here and despite everything that had happened, I felt sad.

In bed that night, I heard a car drive up and the gate rattled. I knew it was Bango, come to scare me, maybe hoping I’d forgotten to lock the gate. I dreaded what would have happened if I had.

The night of my flight, Mohamadin surprised me by showing up to say goodbye.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I was not myself. My mother was sick and then she died. And you went back on your promise.”

“I’m sorry about your mom. But I didn’t go back on any promise. I don’t want to talk about it anymore.” I was tired of the same conversation that never went anywhere.

“But you should not have tried to cheat us like that,” he kept at it.

I reminded him, “Remember when we were first married, I warned you that the minute you disrespected me, even raised your voice, I would be gone. I meant what I said.”

Politely, stiffly, as if we were now strangers, he wished me a good flight and I left.

I was sure I would never be back. I had found out the truth and my dad had been right. But then, something happened while I was in Phoenix, and I returned once more to Luxor. I’m forever thankful I did. That’s when I started Luxor Boxing Girls. That's when I had an epiphany that changed my life and brought me back to my faith in Jesus.

To be continued…

Thank you for reading. May God keep give you strength and courage in these difficult times.

Riveting. Talk about playing with fire! I find it amazing that you escaped. You must have had a force-field of protection.

Oh my goodness, Karen. This is not only an exquisite but extraordinary piece of writing, simultaneously romantic, exotic, evocative and so horrifying that it chills me to the bone. You are a true marvel. I thank G-d that you escaped and weep for those who are unable to. Every single woman in the world, even those who do not appreciate such elegant biographical literature, would benefit greatly from reading your story together with the men who love us. 💋xoBinah